Children of TPS join marchers in Washington by staging urgent play: ‘Will somebody please help me?’

Sophia Landaverde holds out her hands to members of the audience, imploring them to help her family, who may be separated if her parents lose TPS and face deportation.

There’s a scene in a play by the US-born children of Salvadoran immigrants where the effects of President Donald Trump’s restrictive immigration policies become very real. Teens laugh and poke fun at each other while decorating a Christmas tree — until the mood suddenly shifts to fear.

“They don’t want us here anymore,” 14-year-old Kathy Santos says of the US government.

She and another girl had stayed up late listening to their parents discussing what they’ll do when their Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, expires this year as the Trump administration curtails the program.

“They hate us,” Kathy says. “Don’t you see? Next Christmas, none of us will be here.”

“Don’t you see? Next Christmas, none of us will be here.”

Even though this is a stage play, these kids are not acting. It depicts their real lives, real names and real stories. This week, after months of practice, they traveled from their homes in the Boston area to Washington, DC, to perform it Monday for members of Congress and their aides.

The performance was part of a three-day series of events where thousands of TPS beneficiaries came from across the US to meet lawmakers and lobby for legislation that would grant them permanent residency. On Tuesday, they marched with their families in the cold and rain from the White House to the Capitol. They were joined by freshman Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, both Democrats.

It was the largest-ever mobilization of TPS beneficiaries, spurred by the urgency that more than 300,000 of them could face deportation in the coming months as their status expires. For now their futures hang on a court case. The government spending deal set to be passed Thursday does not mention TPS, though Congress and the president floated extending the program during the past several weeks of budget negotiations.

TPS has allowed them to live and work in the US legally for up to two decades. Many obtained advanced degrees, bought homes and started businesses. TPS beneficiaries have collectively raised nearly 280,000 children, nearly all of whom were born US citizens. The past year has been filled with difficult decisions as families wrestled whether to leave their kids behind or bring them along to unstable countries they may never have visited.

But now, their American children have joined the fight to keep their parents in the US legally.

‘They know exactly what is going on’

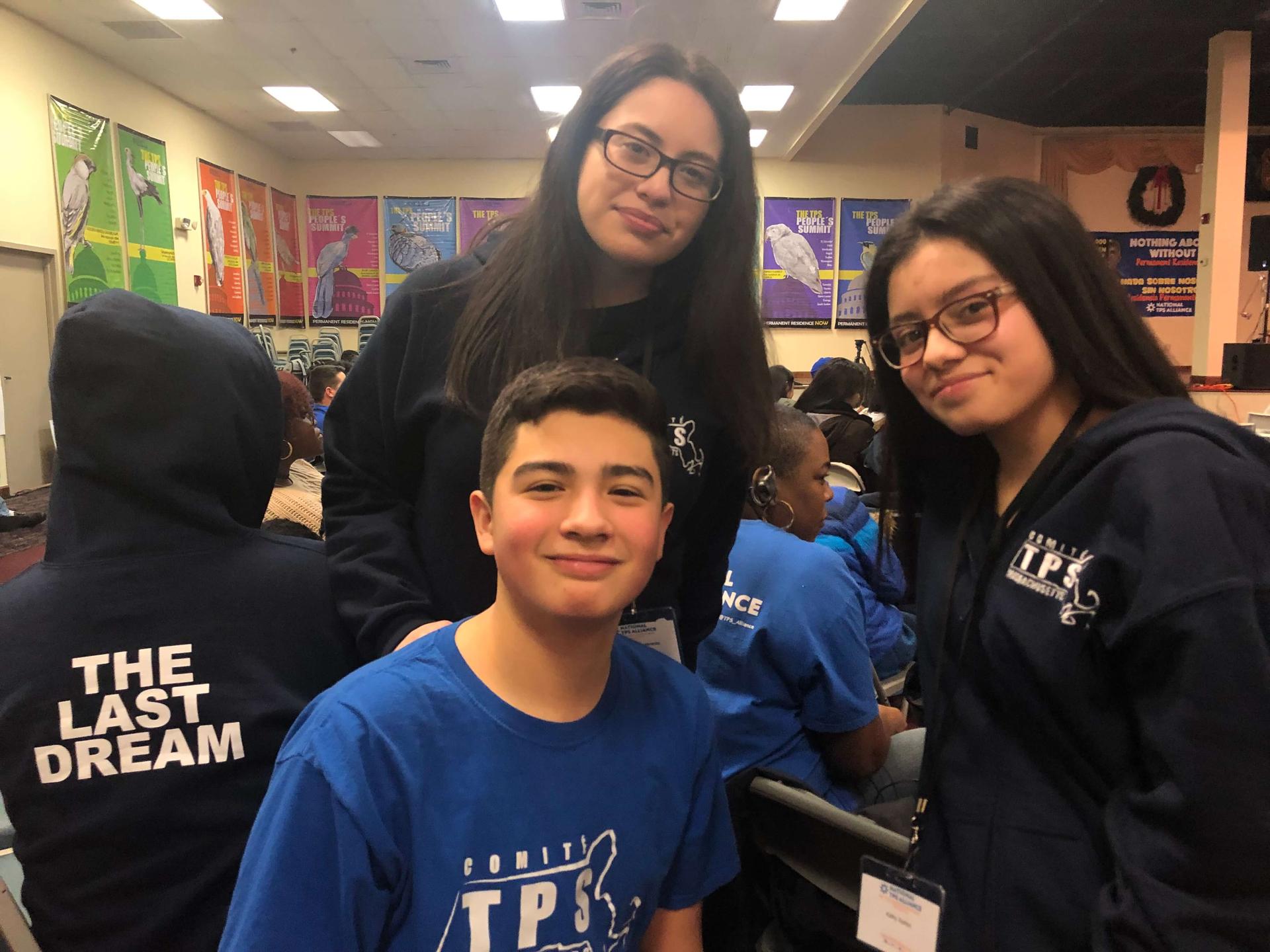

Jose Palma, 42, a father of four and a TPS holder from El Salvador, has lived in the Boston area since 1998. His oldest two children — 17-year-old Kevin and 13-year-old Angela — appeared in the play, as did his 13-year-old nephew, Cristian, who has lived with Palma since his father was deported to El Salvador three years ago.

“As a parent, we’re trying to protect them and tell them, ‘Don’t worry’,” he said last week, as he watched their final dress rehearsal in Boston. “But they were listening to our conversations and watching the news. They know exactly what is going on.”

Palma, a longtime community organizer, is the energetic coordinator of the National TPS Alliance, a rapidly growing coalition of immigrant and labor rights groups from across the country. The alliance has two goals: to save TPS in the short term for all beneficiaries and to get federal legislation passed that will put them on a path to permanent residency.

Since Trump took office in January 2017, his administration has ended TPS designations for six of the 10 countries in the program: El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan. TPS holders have built a national movement from scratch in that time.

“When we started going around to legislators, many of them didn’t even know what TPS is,” Palma says.

Unlike “Dreamers,” who have advocated for themselves for more than a decade, most TPS beneficiaries never felt they had to get involved in activism. Until now.

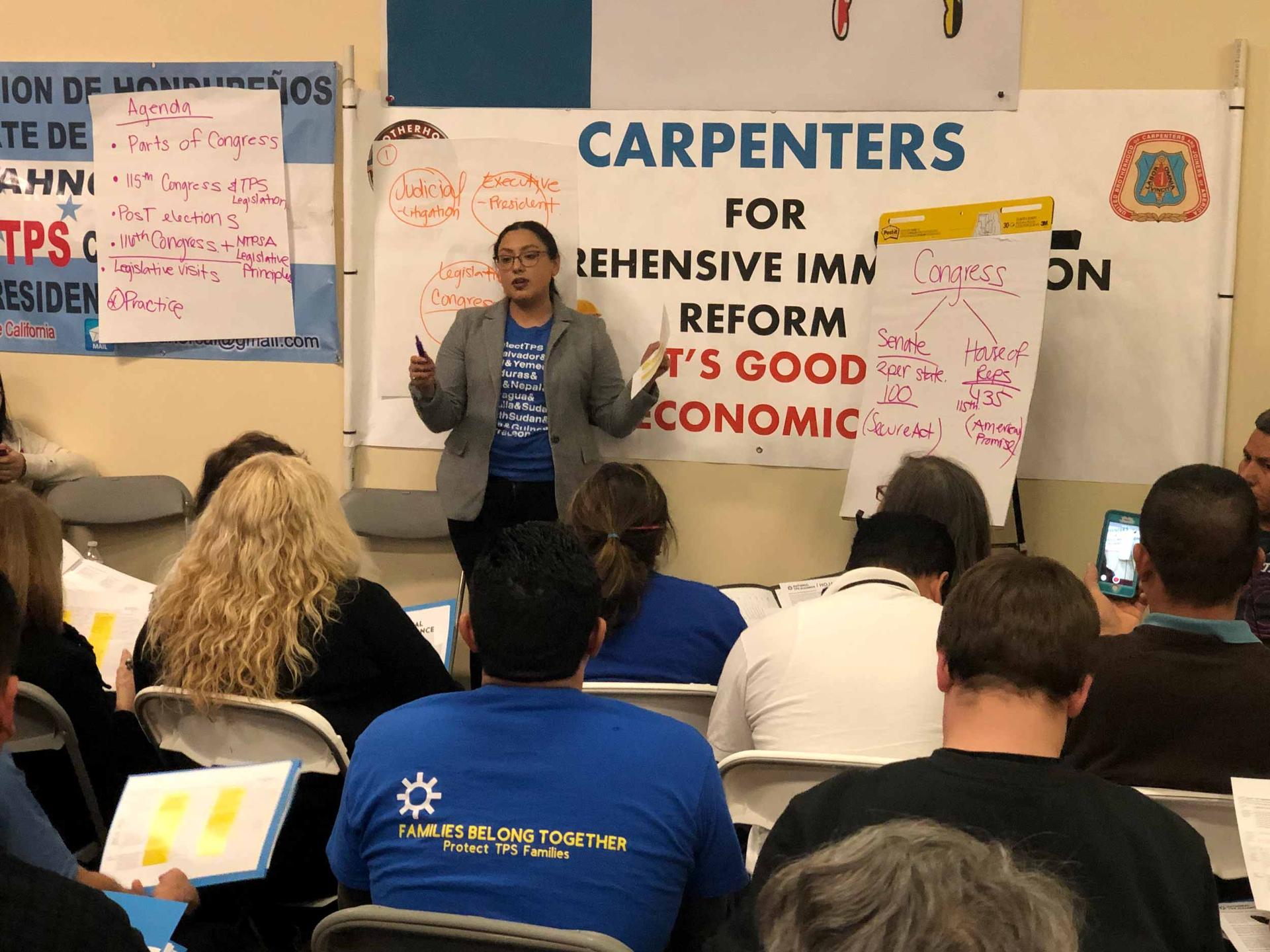

This week’s summit in the DC area brought together a diverse set of people and had simultaneous translation in English, Spanish, Nepali and Haitian Creole. They met Sunday and Monday at the offices of the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades in Lanham, Maryland.

The room was strewn with toys and strollers. Protecting TPS, after all, is a family matter.

As the adults discussed lobbying Congress in the main hall, around 100 kids worked through an agenda of their own in the next room. Children as young as 7 participated in breakout groups on how to use social media to raise awareness of their parents’ plight, and how to involve their schools and communities. They documented their efforts on Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook Live.

‘The Last Dream’

The play was conceived when friends put Palma in touch with Jared Wright, a theater director and former high school English teacher in Chelsea, a heavily Salvadoran suburb of Boston. This was early last year, when Trump had just announced that TPS for Salvadorans would be terminated. Palma asked Wright to lead a workshop to help immigrant adults practice telling their stories for advocacy purposes.

“It was Sunday after church, so they asked if they could bring their kids along,” Wright said. “And when the kids told their stories, they floored us with their honesty and their courage.”

Together with Wright, his wife Emily, and co-writer Donya Pooli, 13 Salvadoran American children aged 10 to 17 wrote, “The Last Dream: Stories Created and Performed by the Children of TPS.”

It’s a production of the Boston Experimental Theatre Company, which was founded by Vahdat Yeganeh, a refugee from Iran. And it was written with lawmakers in mind.

Asked why he’s participating, 13-year-old Brian Pineda managed three words: “For my dad,” he said, bursting into tears. He took a deep breath before continuing.

“It makes me feel like I’m doing something productive and something that would help other people,” he said. “Because, like, what we’re getting in return for this is having our parents here. And other kids are going to get to have their parents here. If we do this, it would be amazing.”

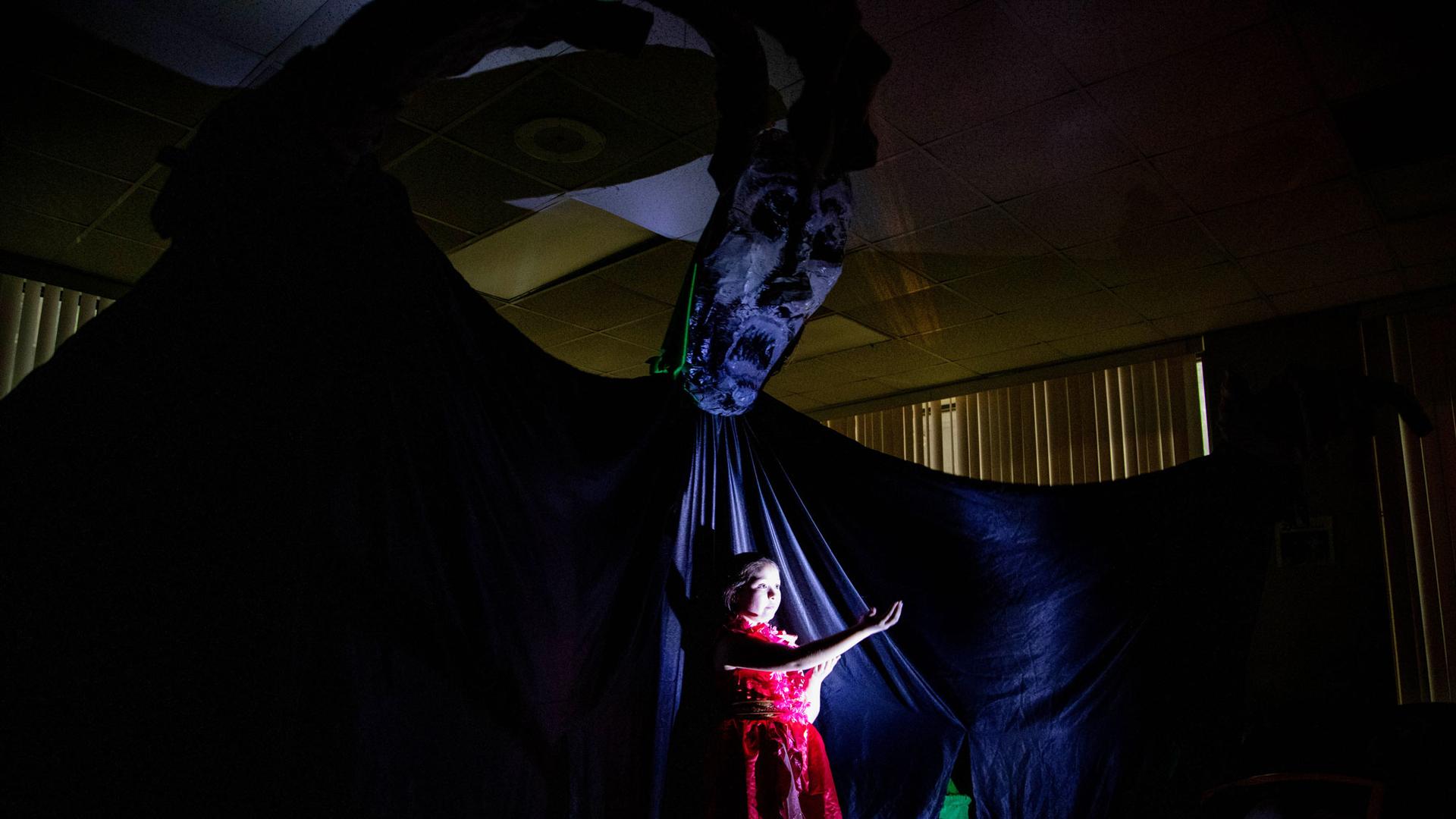

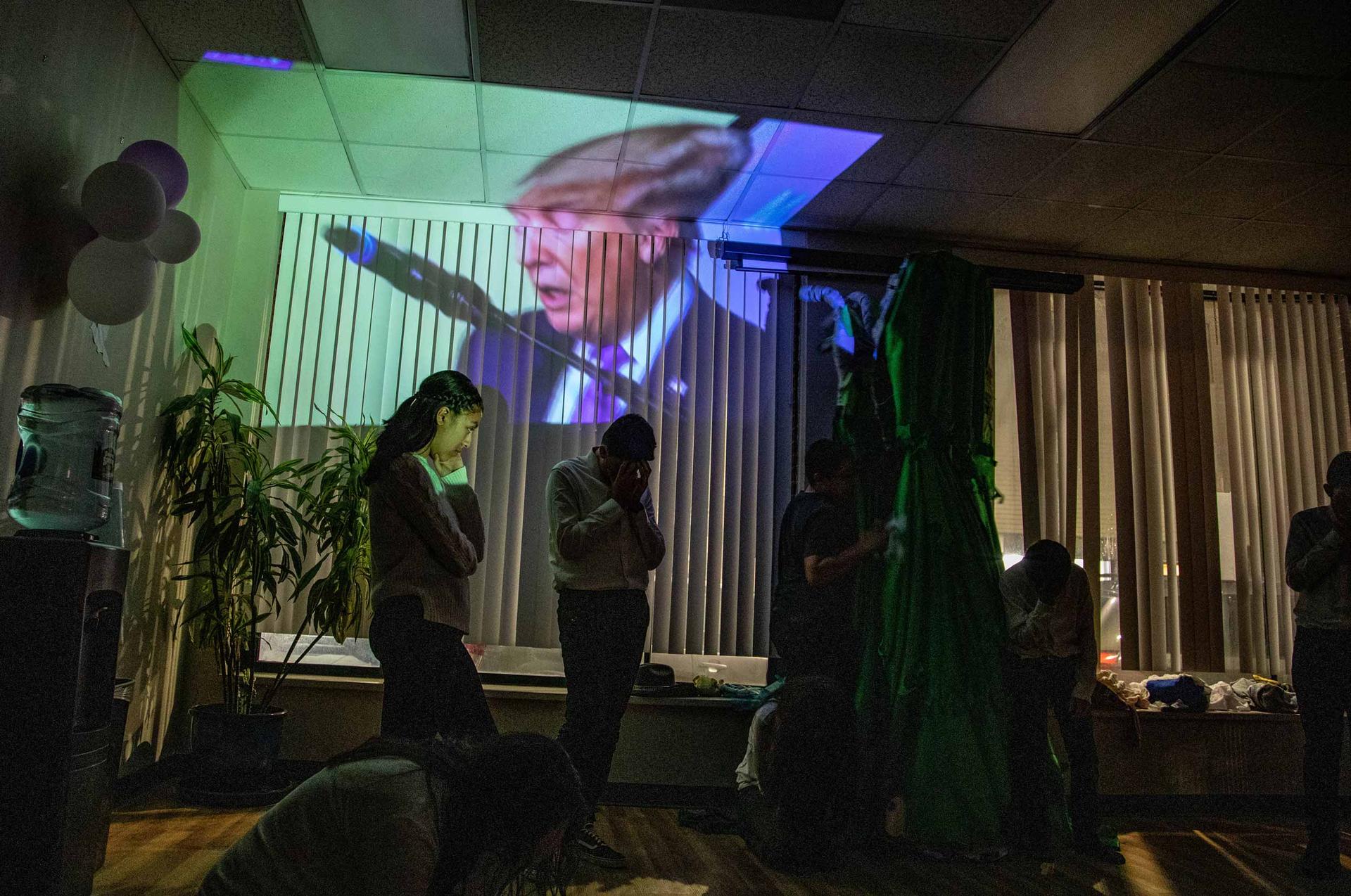

The play begins with a 10-year old Sophia Landaverde sitting alone onstage in pajamas, asking her mother for a bedtime story. A narrator tells of the mother’s happy childhood in El Salvador. But the bright green backdrop is flipped to reveal a giant, angry black monster. News footage announcing the end of TPS is projected on the wall behind them as the monster slowly moves forward and engulfs the children.

“Because, like, what we’re getting in return for this is having our parents here. And other kids are going to get to have their parents here. If we do this, it would be amazing.”

Then, one by one, they state their greatest fears.

“I’m 17, and I’m the oldest of four,” says Jacqueline, Sophia’s real-life older sister. “I want to further my education. But if my family is treated as temporary, I’m afraid I’ll have to give those dreams up and become a mother to my three younger sisters.”

This week, their father, Victor Landaverde, said the family is indeed considering leaving his four daughters behind in the United States if he and his wife lose TPS protections and must return to El Salvador. They’ve also discussed selling their suburban Boston home. Landaverde, who has lived in the US since 1995 and manages a custodial company for Harvard University, came to DC this week to watch his girls’ performance.

“I’m proud,” he said. “But on the other hand, I wish they didn’t feel like they needed to do this.”

The rocky path to permanent residency

TPS is a provisional humanitarian relief program that allows immigrants to live and work in the US if their home countries have been devastated by war or natural disaster — in El Salvador’s case, a 2001 earthquake. Some 200,000 Salvadorans hold TPS, by far the largest group of beneficiaries.

Many TPS beneficiaries arrived in the US illegally, but the program offered legal protection if they were on US soil as conditions worsened back home. It drew them out of the shadows and into the formal economy. By some estimates, the US would lose more than $150 billion in GDP over the next decade if they are removed from the workforce, and their home countries would also suffer from the loss of crucial remittances.

TPS doesn’t offer a pathway to permanent residency or citizenship. Every 18 months, TPS beneficiaries must re-register, a process that includes a background check and $495 filing fee.

“These are people who have been living here legally, paying taxes in the US and having families in the US. They’re part of the legal workforce,” says Theresa Cardinal Brown, a director of immigration policy at the Washington, DC-based Bipartisan Policy Center. “If you’re talking about keeping people who are law-abiding immigrants in the country, this is that group of people.”

Congress established the TPS program through the Immigration Act of 1990, and country designations have been extended by Republican and Democratic administrations alike. The program flew under the radar for nearly two decades, never capturing the legislative agenda or headlines the way DACA did. Over time, a temporary status began to feel permanent.

Lawsuits have been filed around the country challenging Trump’s termination of TPS. A class-action by the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, the National Day Laborer Organizing Network and the law firm Sidley Austin alleges the Trump administration terminated TPS because of racist animus against non-white, non-European immigrants. It also argues the Trump administration violated the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs how the federal government may propose and establish regulations.

The Justice Department counters that the program was only ever meant to offer a temporary reprieve until harsh conditions in their home countries subsided. It has denied allegations of racism.

Harm to US citizen children has been at the center of the ACLU’s legal strategy, explained ACLU lead attorney Ahilan Arulanantham. The lead plaintiff in the case, Ramos v. Nielsen, is Crista Ramos, a high school freshman from the Bay Area whose parents are TPS beneficiaries.

“The most amazing aspect of this litigation has been to see these teenaged American kids go out and tell the world that this administration’s policies are tearing their families to shreds, and publicly rise and take a stand and appear in front of the press and go to Washington,” Arulanantham said.

In October, a California federal judge issued a preliminary injunction in the case that temporarily leaves TPS protections in place for Salvadorans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Sudanese until he issues a final ruling. Judge Edward Chen said the government failed to prove any harm would come of maintaining the status quo. He also noted race was a “motivating factor” in the Trump administration’s decision to end TPS.

“Absent injunctive relief, TPS beneficiaries and their children indisputably will suffer irreparable harm and great hardship,” Chen wrote. “Many have US-born children; those may be faced with the Hobson’s choice of bringing their children with them (and tearing them away from the only country and community they have known) or splitting their families apart.”

The Trump administration has since appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.A similar case was filed Monday on behalf of Nepali and Honduran TPS beneficiaries.

Showtime: ‘Will you help me?’

After months of practice, Monday afternoon was showtime for the Salvadoran American kids from Boston. They’d flown to Washington over the weekend; their 10-foot-tall monster arrived by car. They peeked through the door at their performance space — a meeting room in the Cannon House congressional office building — filled with legislative aides. Pressley’s office hosted the event, and Reps. Jim McGovern of Massachusetts and Jan Schakowsky of Illinois were in the audience.

In the hallway, the children joined hands and said a prayer — a prayer for a good show, one that would convince lawmakers to help keep their parents in the United States. The enormity of the day seemed to sink in.

Then they went in and re-enacted their true stories: the stress of watching the news, their fear of their parents’ deportations and their hopes that somebody in a position of power would listen.

In the final scene, Sophia Landaverde wore a silky red birthday dress as she held her hand out to one half of the audience.

“Will you help me?” she asked, her voice shaky.

She turned to the other half. “Will you help me?”

“Will somebody please help me?”

When the lights came up, every child was in tears.