Therapists help migrants in San Antonio through trauma after detention

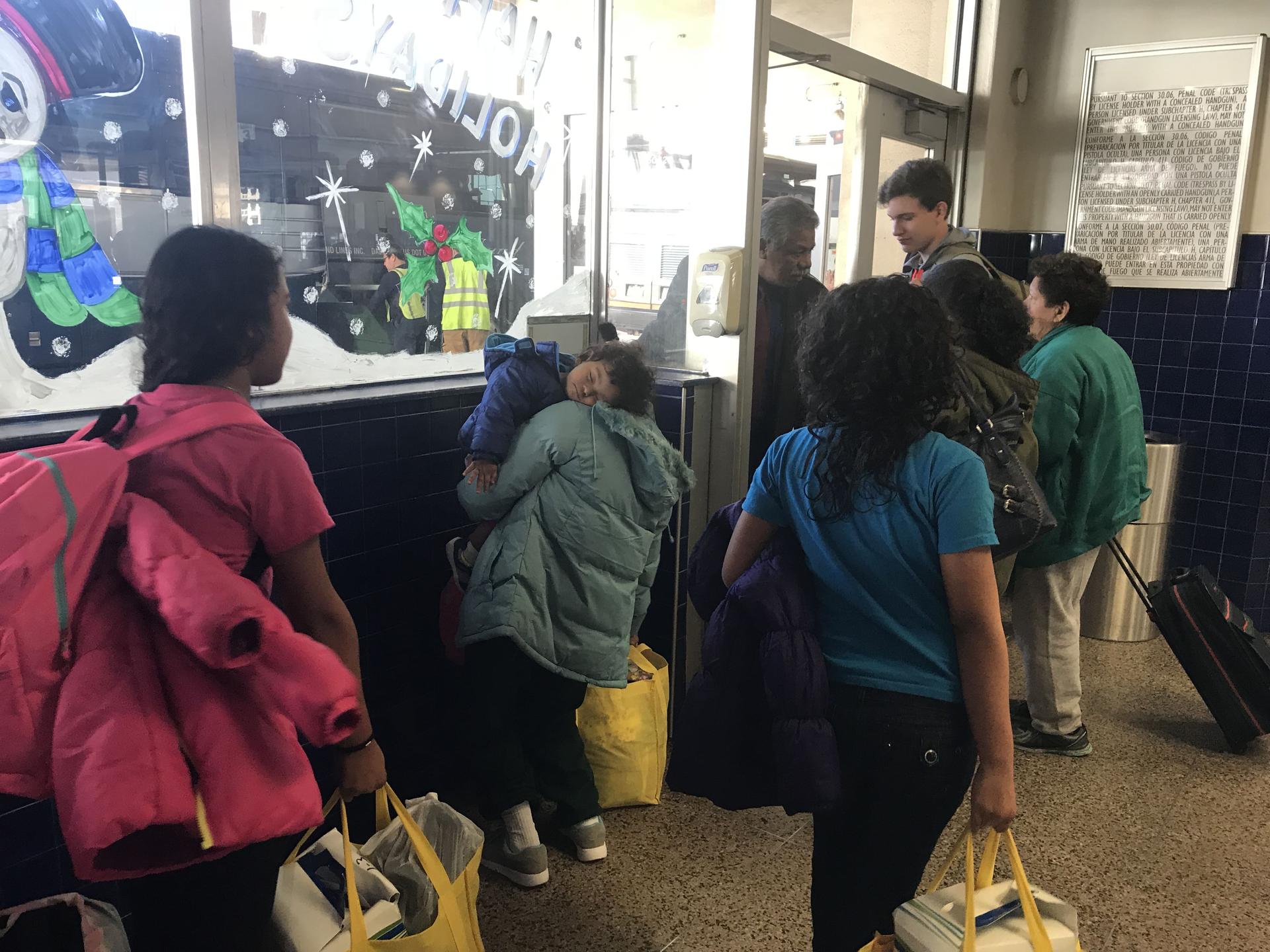

Alicia Cruz, a therapist working in San Francisco, Calif., comforts a mother just released from ICE detention to a San Antonio bus station.

On a chilly January morning, two psychotherapists from California arrived at the Greyhound bus station in San Antonio, Texas, to meet with dozens of migrant families who had just been dropped off by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

The two bilingual therapists, Alicia Cruz and Chris Mullen, have worked together for a decade at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center and see clients in offices right next to each other. They were prepared to put their therapeutic skills to use in a most unlikely place: the waiting area inside the bus station.

It was easy for the women to spot the parents and children just released from detention. They were wearing brightly colored sweat suits, parkas and brand-less tennis shoes issued to them by ICE. The families were delivered there from the country’s two largest ICE family detention centers, each about an hour away, and issued one-way tickets to travel on to relatives or sponsors around the country.

The families crammed onto metal benches with bags of belongings stuffed under their feet. Several nuns and volunteers from local churches handed out box lunches and backpacks containing toiletries and stuffed animals for the kids.

Clipboards in hand, Cruz and Mullen worked their way down the rows of benches, offering legal information. They also asked parents if they were willing to talk about their experiences crossing the border.

Mullen and Cruz were so moved by news accounts of migrant families being detained at the border that they used vacation days for the trip, working with RAICES, a Texas nonprofit that provides legal help to asylum seekers.

“I told my boys, ‘It’s not a choice for me. I’ve got to go help,’” said Cruz, whose two sons, ages 7 and 11, have helped collect toys to donate to the children in Texas. “It was an immense pull that I couldn’t really explain.”

More Central American Families Seek Asylum in the US

Although the total number of people apprehended crossing the US-Mexico border has dropped significantly in recent years, the number of families has grown dramatically, from 15,000 people traveling in families in 2013 to 107,000 last year. Most are fleeing gang violence, government corruption or extreme poverty in their home countries in Central America.

Last year, after a controversial family separation policy was struck down by the courts, the Trump administration proposed a plan to hold parents and children indefinitely in ICE custody — part of an effort to terminate a longstanding legal agreement that limits ICE detention of children. But ICE has space for about 3,600 people in its three family facilities nationwide — far below recent demand. Advocates in Texas say the families released at the bus station have typically been held by ICE for a week or two.

Many of the families Cruz and Mullen met at the Greyhound station were coughing and had fevers, looking dazed in their first moments of freedom.

Cruz said these families have been through a lot. After surviving violence in their home countries, she said, they are often re-traumatized by the dangerous journey here and their time in US detention.

Cruz and Mullen handed out plastic bags of Legos to the children so they could play while their parents talked. Most of the migrants didn’t want their names used because they fear for the safety of their families. Mullen sat down with a man from Guatemala while his 9-year-old son drew in a coloring book nearby. Mullen asked him why they left home.

“Honestly, I had never thought of leaving, because everything I have is there,” the 29-year-old father replied.

He told Mullen that drug traffickers had built airstrips in the jungle near his town, and he saw local police driving back and forth each time airplanes landed. One day a friend told him his name was on a government official’s hit list. The next day, that friend disappeared. That’s when he knew he had to leave.

As the man spoke, tears dropped steadily onto the sleeve of his jacket. He told Mullen he crossed the border into California last month by climbing a tree with his son clinging to his back and leaping onto the wall, then down onto US soil.

“I told my son to grab my neck and hold on really tight because I was going to jump. I told him, ‘You have to hold on so you don’t fall.’”

“I told my son to grab my neck and hold on really tight because I was going to jump,” he said. “I told him, ‘You have to hold on so you don’t fall.’”

The man said he and his son spent six days in a Border Patrol station, where they were given cold bean burritos for every meal, before they were transferred to an ICE facility for fathers and their sons at Karnes City, Texas. Now they are heading to the East coast to stay with relatives while their asylum claim is adjudicated.

Limits to Detention

Under a 1997 legal settlement known as Flores, along with the 2008 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, unaccompanied migrant children are not supposed to be held in US Customs and Border Protection facilities for longer than 72 hours except in “exceptional circumstances,” and they must be provided adequate food and shelter during their stay.

Last year, attorneys for migrant children filed affidavits with a federal judge documenting numerous violations of the settlement. These included migrants’ lack of access to clean drinking water, being fed inadequate or inedible food, and being subject to unsanitary conditions, extreme cold and sleep deprivation.

But after two children died in CBP custody in December, officials indicated they would work to transfer parents and children to ICE family detention centers more quickly. The Department of Homeland Security declined to confirm whether that has occurred yet.

In an email to KQED, DHS spokeswoman Katie Waldman called the current situation “an immigration crisis,” and blamed the federal courts for creating a “loophole that rewards parents for bringing their children with them to the United States.”

“As long as activist judges continue to set national immigration policy they continue to put family units and innocent children in harm’s way,” she added.

In dozens of interviews in the Greyhound station, parents from Central American countries described dire conditions they endured.

One young mother, also from Guatemala, told Cruz she fled because a gang tried to extort money from her and threatened to kill her family when she did not pay up. As she described crossing the Rio Grande with her 10-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son, she started to cry, remembering her fear that they might die.

“When we crossed the river, we got lost,” she said. “We didn’t have any water to drink. We spent four, five hours lost before we got picked up by immigration.”

The mother told Cruz that Border Patrol agents locked the family in a cold, windowless room for four days, and only gave them one sandwich and one juice box a day. When her children cried, she said, agents told her to shut them up.

“’This isn’t your country’,” she said they told her.

After the family was transferred to ICE, the mother said they were given enough food to eat and access to showers, but she told Cruz she regrets putting her children through the experience.

“I thought it would be easy to come here,” she said. “People told me, ‘Just turn yourself in to immigration!’ But no, it’s very difficult.”

Cruz listened attentively and reflected back what she’d heard: that the mother made the only choice she could.

“The truth is you didn’t come because you wanted to, you came because you had to,” Cruz said. “It’s important to remember that even though your children suffered, you had to come to survive.”

The woman nodded and wiped away her tears.

A couple of hours later, she and her kids boarded a bus to San Francisco — a trip that takes 39 hours. In her pocket was some cash Cruz gave her for meals, along with the name of a trauma recovery center in San Francisco that works with asylum seekers.

Cruz said many of these families will need ongoing help to recover from what they’ve gone through.

“You could see sometimes how intense and overwhelmed they are when they’re reliving their trauma, because it’s still very raw and fresh.”

“You could see sometimes how intense and overwhelmed they are when they’re reliving their trauma, because it’s still very raw and fresh,” she said.

She and Mullen also know that the migrants will need to be able to talk about their experiences in a coherent and compelling way when it comes time for an interview with an asylum officer, known as a “credible fear” interview.

Mullen said when someone is in a state of shock, they don’t always sound convincing.

“When you’re really disconnected — and that’s often the case with PTSD — it sounds insincere and also it can be very vague,” she said.

The two women spent five long days counseling migrants at the bus station. After flying home to her own children, Cruz said she struggled to process what she heard from parents about the mistreatment of children in Border Patrol custody.

“How they were being yelled at for crying, or manhandled,” Cruz said. “I can’t imagine how their brain makes sense of that — because they are so little. As someone in the mental health field, that really worries me how this is all going to manifest itself in this child as he grows up.”

This story was reported in collaboration with KQED. Read the original here.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?