Supporters of the anti-Islam movement PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West) attend a demonstration in Dresden, Germany, on Oct. 21, 2018.

Right-wing extremism is on the rise in Germany.

The number of far-right extremists is up by a third this year, according to German intelligence services. Dresden, in East Germany, is attempting to confront the problem by declaring a “Nazi emergency” in the city in November 2019.

But the announcement is simply a motion passed by the city council with no obvious solution, residents say. The far-right party Alternativ fur Deutschland (AfD) said it is merely a political stunt by disgruntled opposition parties.

Are they right or does the city have a Nazi problem?

Related: Artists in Germany fear backlash after far-right party wins big

Once a month, a group of middle-aged and older men and women gather in the center of Dresden to sing old German ballads and listen to speeches at a small makeshift stage.

Some wave German flags and hold up homemade placards with pictures of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s face pasted to the front. The only indication that this is not an innocuous community gathering is the ring of police who stand silently nearby.

This is PEGIDA, an anti-Islam movement that began in Dresden in 2014 and at one point brought thousands of supporters to the streets of the East German city. PEGIDA stands for “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West.” The posters of Merkel bear the words “terrorist” and “war criminal.”

Related: Germany’s refugee crisis is a gift to the far-right PEGIDA movement

The AfD party in Dresden counts PEGIDA members among its supporters. AfD councilor Wolf Hagen Braun said while he may not agree with everything they say, he defends the rights of PEGIDA members to protest. Braun is dismissive of the motion declaring a “Nazi emergency” which was passed by his fellow city councilors. It’s all about party political differences, he said.

“There’s been increasing polarization in the political atmosphere here. And this has led to our political opponents using more radical measures to attack us,” Braun said.

That’s not how Max Aschenbach, who proposed the motion, sees it. Aschenbach, a councilor with the satirical party Die Partei or “The Party” sees a steady rise in racism being expressed on the streets of Dresden.

“Everyday there are police reports about swastikas and Hitler salutes; it has become a part of everyday life.”

“Everyday there are police reports about swastikas and Hitler salutes; it has become a part of everyday life.”

What’s worse, he said, is that politicians both locally and nationally are also using racist language.

“Whether it’s the cashier in the supermarket uttering racist rubbish when an apparent foreigner passes, or whether these are statements from politicians — not just in Dresden but on the federal level, too — politicians who talk about ‘asylum tourism’ and make tendentiously racist comments.”

The motion is a controversial one and made news headlines around the world when it was first adopted. Some councilors worry it will damage Dresden’s reputation and link the city forever with extremism. Aschenbach shrugs. Pegida, he said, managed to do that already without his motion. He wants other political parties to voice concern at the rise in popularity of far-right parties like the AfD and accept the city “has a problem with Nazis.”

Does the AfD party have a Nazi problem? Political scientist, Christoph Meisselbach at the Technical University in Dresden thinks so. And it’s a “problem that should not be underestimated,” he said.

Meisselbach cites Bjorn Hocke as an example of the extremist element within the far-right party. Hocke is a controversial figure in the AfD. He once said Germany was “crippled” by its “stupid” politics of remembrance and dismissed the Holocaust memorial in Berlin as a monument of shame. Meisselbach believes these views actually attract more people to the party.

“The AfD doesn’t get elected despite the fact that there are these radicals, but also because there are these radicals.”

There is a danger though that the term Nazi gets thrown around all too frequently in relation to the AfD. While extremists are attracted to the party, many of those who voted for the far-right party did so because traditional right-wing parties like Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) moved increasingly to the center, Meisselbach said.

The voters were looking for a more conservative right-wing alternative and the AfD stepped in. Supporters also felt marginalized by the political system and the AfD presented itself as an anti-establishment alternative. The support for the far-right party is much more pronounced in parts of East Germany than in the West, a fact Meisselbach and others attribute to the poorer economic circumstances many in the east found themselves in after the fall of communism.

Related: 30 years after it fell, the Berlin Wall still divides Germans

Regular PEGIDA marches and the rise of the AfD have made things uncomfortable for the Muslim community in Dresden.

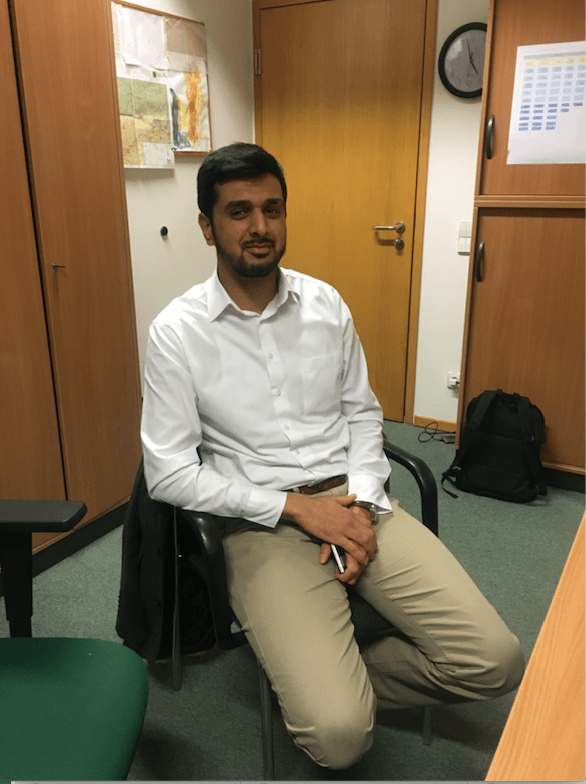

Imam Umer Malik said there is an issue with Nazis in the region and some people think nothing of being openly racist on the streets. He is careful to emphasize the “good people of Dresden,” though. He recounts that at one point, there were anti-Islam demonstrations outside the Islamic Cultural Center in Dresden every Friday. But authorities quickly intervened and the protests stopped. The center itself is called Marwa El Sherbini Zentrum, named after an Egyptian woman who was stabbed to death in 2009 in Dresden. The court later ruled that her killer was partly motivated by a “hatred of foreigners.”

Imam Malik is not worried about his own safety even if AfD support continues to rise. His own parents fled from Pakistan because of religious and political persecution. They were granted asylum and settled down in Wiesbaden. Malik said his parents were always made to feel welcome in Germany and he feels safe because he was born there.

“I’m a German. They can’t restrict me to live. This is a fundamental right. I’m a human being.”

“I’m a German. They can’t restrict me to live. This is a fundamental right. I’m a human being.”

Meisselbach, the political scientist, is not convinced the “Nazi emergency” motion will achieve much. There is a danger it may play into the hands of the far-right party, who can use it to their advantage, he said.

“They [AfD] will say to their supporters instead of trying to understand what made us successful, they just call you Nazis again and again and delegitimize your demands. So, who will be there for you? Answer: we will be.”

Weeks after the motion passed, however, intelligence services have changed the way they identify right-wing extremists in Germany. The country’s federal domestic intelligence service (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz or BfV) and state-level intelligence services for the first time included groups affiliated with the AfD when providing figures in their 2019 report on extremism.

The move is likely influenced by a series of deadly incidents in Germany this year including an attack on a synagogue in Halle, a city in central Germany, in October, when two people died, and the killing of pro-immigration politician Walter Lubcke by a right-wing extremist in May.

For Aschenbach, the councilor with the satirical party Die Partei, it may seem that his motion is finally having an impact.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?