Slavers in the family: What a castle in Accra reveals about Ghana’s history

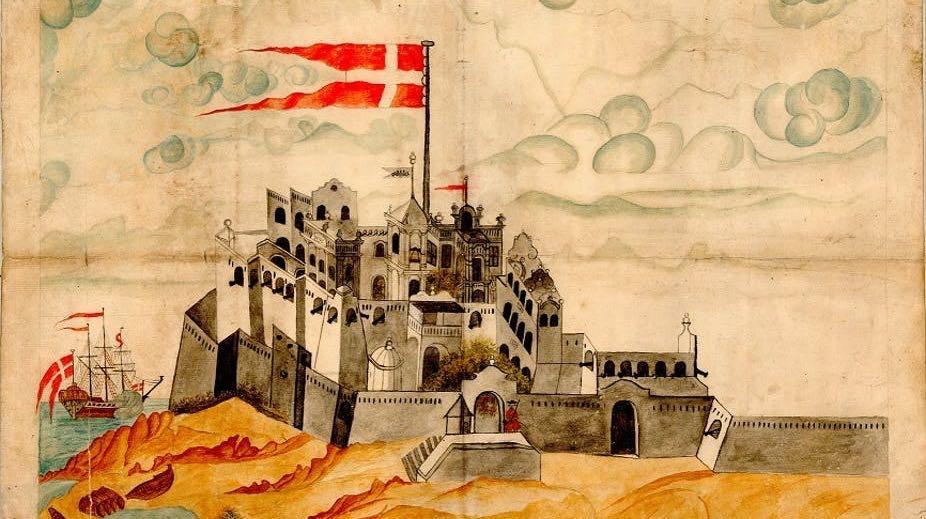

Archival illustration of the Christiansborg Castle.

As a Ghanaian archaeologist, I have been conducting research at Christiansborg Castle in Accra, Ghana. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the castle is a former 17th-century trading post, colonial Danish and British seat of government, and office of the president of the Republic of Ghana. Today, it’s known in local parlance as simply “Osu Castle” or “The Castle.”

My research is the first archaeological excavation of the castle. I became interested in the history of the castle when several years ago, my aunt remarked: Go to the castle and see your surname inscribed on the castle wall.

Related: A professor with Ghanaian roots unearths a slave castle’s history — and her own

I was confused. The story I’d grown up with was that my family — the Engmanns — descended from a Danish Christian missionary stationed on the coast. As I discovered after taking my aunt’s advice, there was a great deal that I did not know.

When visiting the castle, I noted a water cistern in the courtyard inscribed with the name “Carl Gustav Engmann.” This led me to the Danish National Archives, where I studied boxes of archival manuscripts written by Engmann. What I learned during this early part of my exploration was that Engmann — my great-great-great-great-great grandfather — was in fact a governor of Christiansborg Castle from 1752 to 1757. He later became a board member of the Danish Slave Trading organization between 1766 and 1769.

Related: Resistance and collaboration: Asameni and the keys to Christiansborg Castle in Accra

What is more, oral and ethnographic accounts in Ghana revealed that during Engmann’s time on the coast, he married Ashiokai Ahinaekwa, the daughter of Chief Ahinaekwa of Osu, from whom I am descended.

The castle

The castle is situated on the West African coast, formerly and notoriously known as the “White Man’s Grave.” The castle’s origins can be traced to a lodge built by Swedes in 1652. Nine years later, the Danish built a fort on the site and called it Fort Christiansborg (“Christian’s Fortress”), named after the King of Denmark, Christian IV.

Over time, the fort was enlarged and converted into a castle.

An impregnable imperial fortification, the castle contained a courtyard, chapel, “mulatto school,” warehouse storerooms, residential quarters, dungeons, bell tower, cannons and saluting guns.

The castle was so vital to the Danish economy that between 1688 and 1747 Danish coinage depicted an image of the castle and the inscription, “Christiansborg.” The castle operation included a governor, bookkeeper, physician and chaplain, alongside a garrison of Danes, in addition to Africans, known as “castle slaves.”

Between 1694 and 1803, guns, ammunition, liquor, cloth, iron tools, brass objects and glass beads were exchanged for gold and ivory, as well as enslaved Africans. Approximately 100,000 enslaved Africans were transported to the Danish West Indies, comprising St. Croix, St. John and St. Thomas islands.

The Danish Edict of 16 March 1792 officially marked the end of the Danish trans-Atlantic slave trade, though it was not enforced until 1803.

Apart from a few brief periods, the site remained occupied by the Danish. In 1850, Denmark sold Christiansborg Castle to the British for 10,000 pounds.

Local communities

At the castle, we adopt a collaborative, democratic approach to archaeology, working with local communities. The team includes Danish-Ga direct descendants whose ancestors lived close to the castle during the 18th century, and who continue to do so today.

Its focus on an archaeology “for, with and by” direct descendants emphasises its decolonizing agenda. For these reasons, I use the term “autoarchaeology.”

Ultimately, it contests archaeologists’ legitimacy, authority and self-proclaimed exclusive rights as stewards, interpreters and narrators of the material past.

Prioritizing direct descendants’ narratives and the histories they reconstruct, sheds light on little-known episodes in the history and legacies of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. At the same time, it reveals the complexities of the politics of the past in the present.

Together, we are rewriting history.

Words and things

As a historical archaeology project, we employ a “multiple lines of evidence approach” to research. We combine several sources — objects, texts, oral narratives and ethnography since there are multiple, often competing understandings of the past.

In this way, our work challenges traditional historical interpretations of the trans-Atlantic slave trade based on European colonial written accounts. Such sources present history from a European (often white, male, elitist) colonial perspective, frequently marginalizing or disregarding African and Afro European experiences.

We have excavated an extensive precolonial settlement. This includes the foundations of houses and what is tentatively thought to be a kitchen since it contains three stones (for balancing a cooking pot) and charcoal, in keeping with local cooking area design.

We have also retrieved what are commonly known as “African trade beads” that were produced in various parts of Africa, as well as Europe, including Italy and Holland. Ceramics include Chinese and European ceramics (Wedgewood and Royal Doulton), alongside local pottery.

An African smoking pipe and numerous Dutch, English, German and Danish clay smoking pipes were recovered from the site. European glassware ranges from every day usage to refined, luxury ware. There are a number of other small finds including a slate fragment, typically used for writing, as well as faunal remains, seeds, metals, stone, daub, cowrie and other shells.

With the assistance of local fishermen, we even excavated a canon immersed in sand that had fallen from the castle above on to the beach below. Under the castle, we also discovered the entrance to an underground tunnel that led to the nearby Richter House, formerly owned by a successful “mulatto” Danish-Ga slave trader. This tunnel meant captive Africans could be transported from the house directly onto slave ships at sea without much opportunity for escape or drawing the attention of others.

Future plans

We plan to continue with the archaeological excavations, artifact analysis and educational outreach. The project has received generous support from all the current and former presidents of Ghana, the national government, Osu chieftaincies, Osu Traditional Council and the Osu community — without it this project would not have been possible. The excavated artifact collection will contribute to plans to develop the castle into a museum.

In the meantime, I’ll continue to wonder which one of these thousands and thousands of artifact fragments once belonged to my great-great-great-great-great grandfather.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. It was written by Rachel Ama Asaa Engmann, assistant professor of African studies, archaeology, anthropology and critical heritage at Hampshire College.