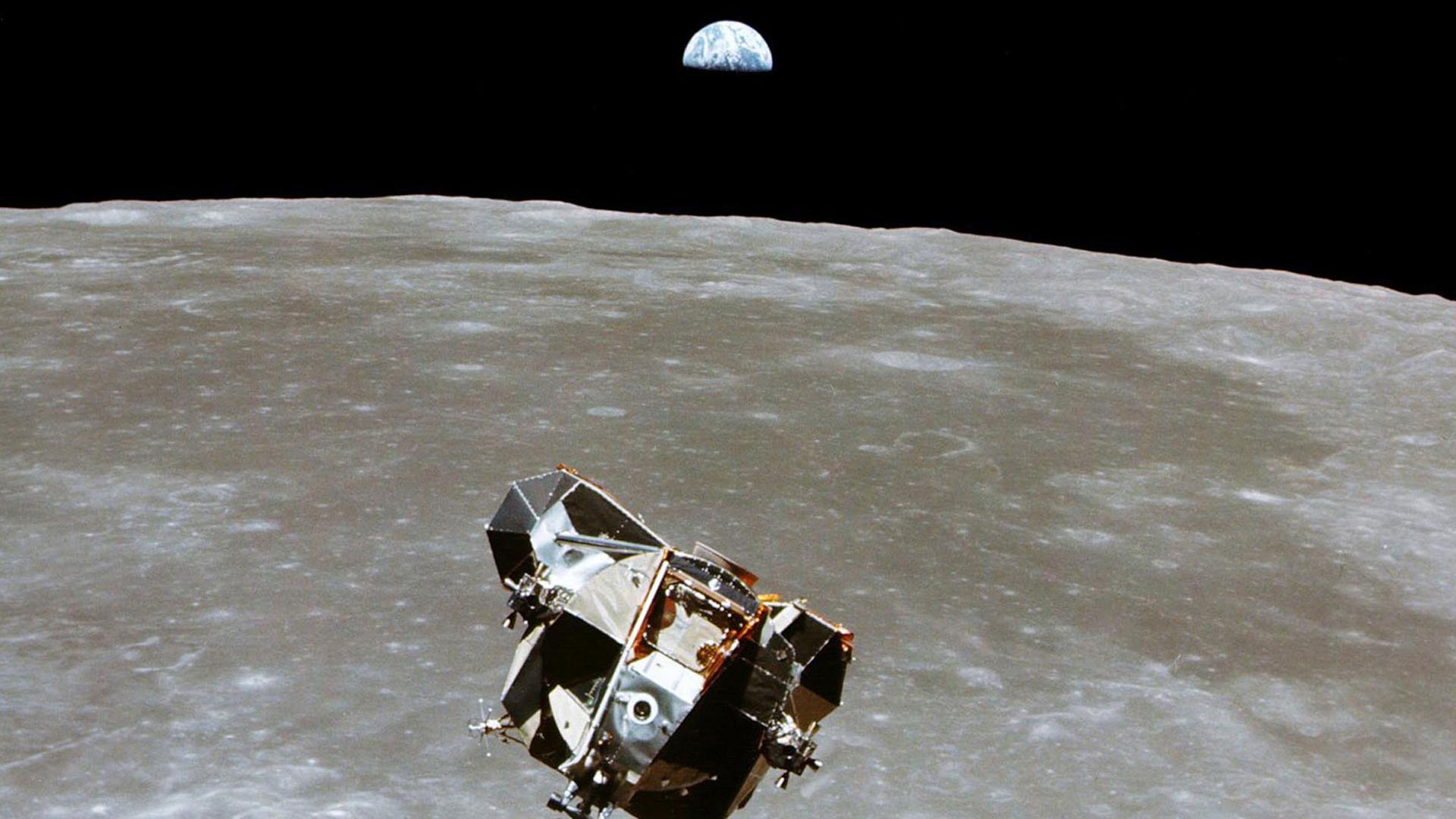

It has been a half-century since Neil Armstrong stepped out of a lunar module and onto the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969 and declared, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The moment heralded a golden age of space exploration that was set in motion just eight years earlier in 1961, when President John F. Kennedy promised before Congress to put a man on the moon before the decade was out.

Here are some lesser-known facts about the historic first mission:

1. Armstrong almost didn’t survive training

Neil Armstrong was training as the backup commander for the Apollo 9 mission a year before his historic mission as Apollo 11 commander, carrying out a simulated lunar module landing when he lost control of the airborne vehicle at Ellington Air Force Base in Houston. At 200 feet up in the air, Armstrong decided to eject, and the vehicle crashed and burned on impact only seconds later as he floated safely to the ground in a parachute.

Armstrong recalled that the simulations were much harder than the actual landing, because Earth-bound tests had to account for wind, gusts, turbulence and other factors not present in the airless environment on the moon.

“The systems were somewhat choppier or less smooth than the actual lunar module, both propulsion and altitude control systems were so,” he said in a 2001 interview for a NASA oral history project. “The lunar module was a pleasant surprise.”

2. The women behind the mission

NASA research mathematician Katherine Johnson wrote the calculations for the Apollo 11 trajectory to the moon. She was one of just a few African-American women hired to work as “human computers” to check and verify engineer calculations at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the agency that preceded NASA. Johnson was a key contributor to several space milestones.

Johnson wrote the trajectory for Alan Shepherd’s flight in 1961, the first by an American in space, and the verification of calculations for John Glenn’s 1962 orbit, the first by an American. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 and her life story was turned into the 2016 film “Hidden Figures.”

Related: A team of women is unearthing the forgotten legacy of Harvard’s women ‘computers’

3. A pocket full of moon dust

After Neil Armstrong made his historic first step onto the surface of the moon, he grabbed a handful of rocks and soil and stowed it in the pocket of his spacesuit as a “contingency sample.” If the astronauts had to hurry off the surface, at least scientists had some material to work with.

Armstrong remarked on the landscape: “It has a stark beauty all its own — like the high desert of the United States.” Years later in a 2001 interview, Armstrong also expressed curiosity at the simple things in the lunar atmosphere: “There was no dust when you kicked … That’s a product of having an atmosphere, and when you don’t have an atmosphere, you don’t have any clouds of dust.”

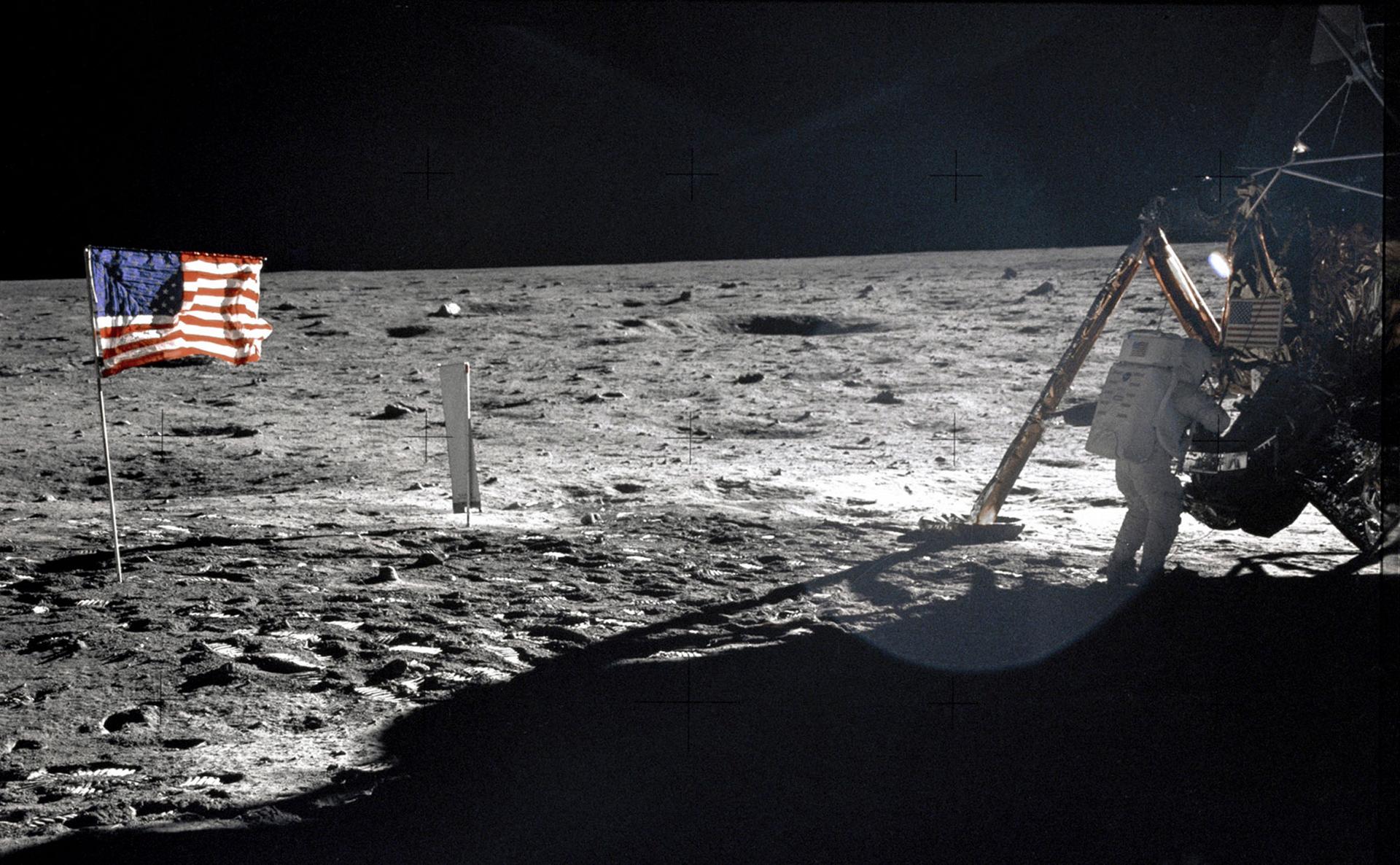

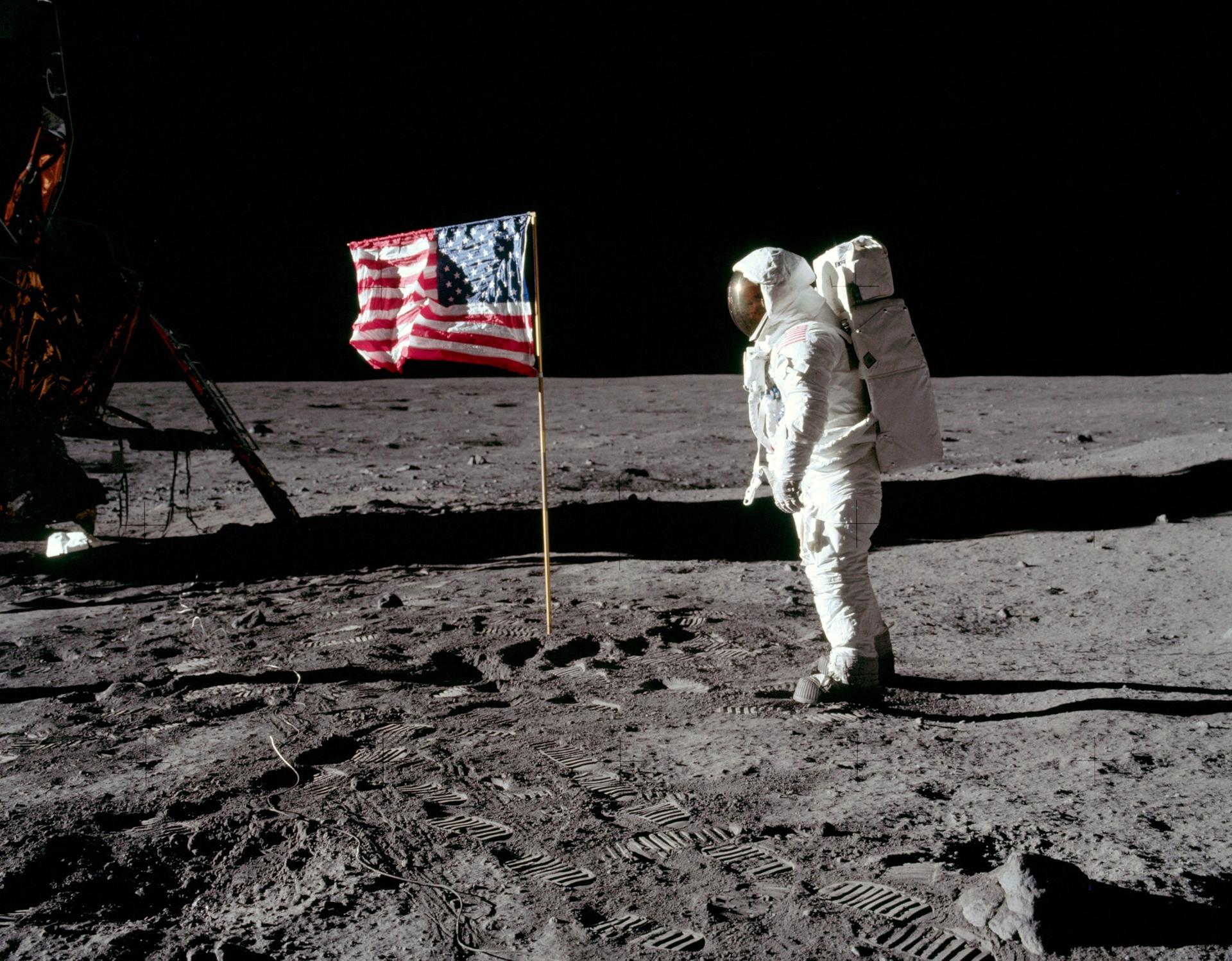

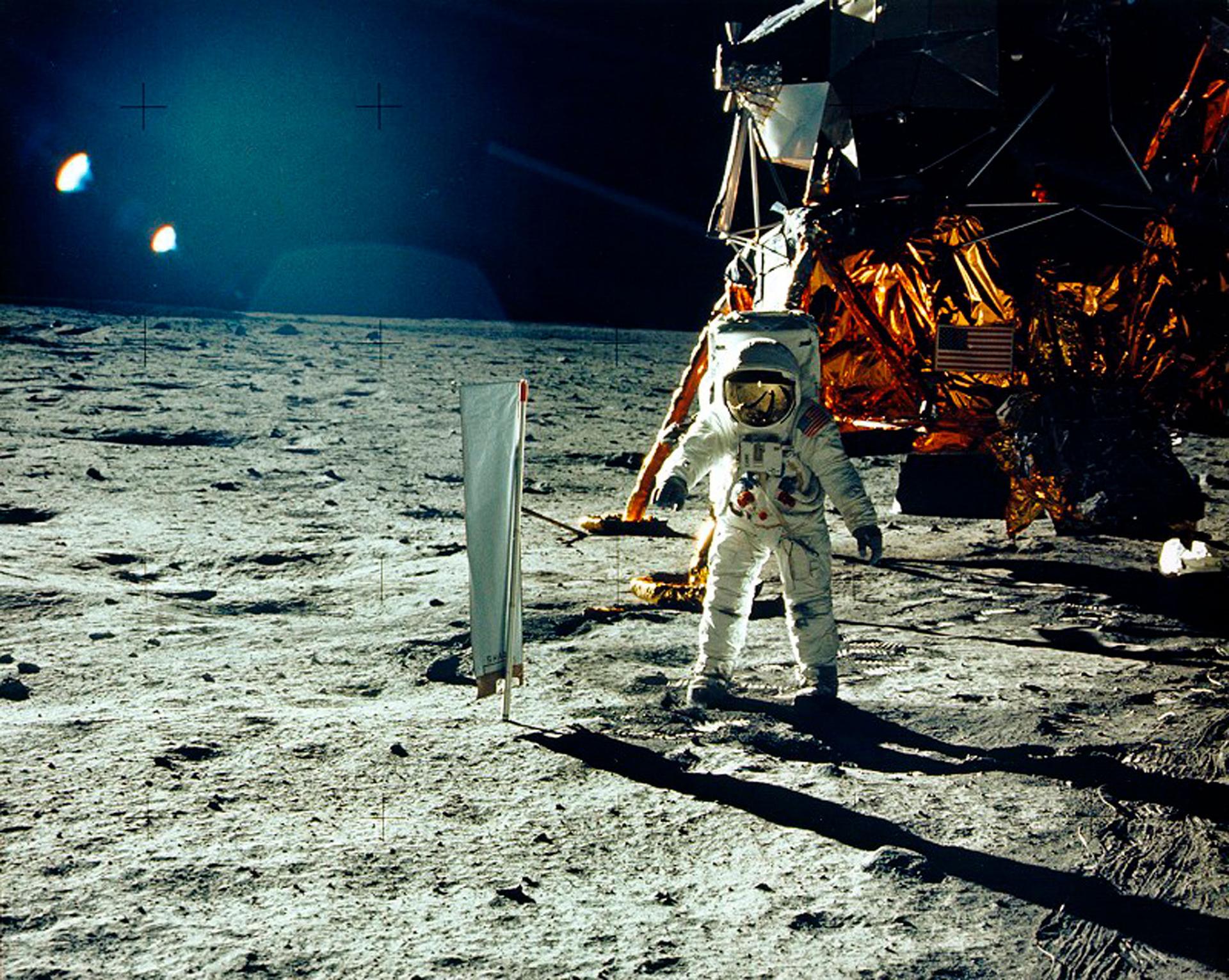

4. ‘Flying’ the flag

The US flag that was famously planted by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin was customized so it could ‘fly’ in the airless lunar environment. Designers Jack Kinzler, technical services division chief, and deputy division chief David McCraw sewed a hem onto the top of a standard 3×5 nylon flag and slipped in an aluminum rod that would hold the flag out to the side.

The flag is likely no longer standing — photographs in recent years show flags from later Apollo missions still upright, but not 11. Buzz Aldrin says that as the lunar module lifted off from the moon at the end of the Apollo 11 expedition, he saw it being beaten by the engine’s exhaust.

5. Moon rocks

The crew gathered 47.51 pounds of rocks and soil from the moon. Three minerals were discovered from samples: armalcolite, tranquillityite and pyroxferroite.

Armalcolite, first found in the Sea of Tranquility, was named for the crew of the Apollo 11 mission: Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. The mineral was later also found on Earth.

6. Armstrong’s famous first line

Neil Armstrong reflected on his famous first line, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” after stepping onto the moon’s surface. In a 2001 interview for a NASA oral history project, he said that while he did ponder what to say, he was preoccupied with more immediate tasks in the period after landing and before venturing out in his spacesuit.

“It … was a pretty simple statement, talking about stepping off something. Why, it wasn’t a very complex thing. It was what it was.”

7. Welcome committee in the Pacific

The crew splashed down in the North Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969, some 900 miles southwest of Hawaii, and were met by Lieutenant Clancy Hatleberg of the US Navy’s Underwater Demolition Team-11 at the floating capsule. Hatleberg carried biological isolation garments for himself and the crew members, in case they had been infected with extraterrestrial microorganisms.

The astronauts put on the suits before getting on the life raft, and Hatleberg then sprayed down the capsule, the astronauts and himself with disinfectant before they were plucked from the water and brought aboard the USS Hornet recovery ship.

The crew wore the suits from the moment the hatch was opened until they were sealed inside a quarantine unit on board the USS Hornet. When the ship docked in Hawaii, the sealed unit was loaded onto a US Air Force transport plane and flown to Ellington Air Force Base outside Houston, Texas, where the three astronauts waited out the full quarantine period of 21 days.

8. Guarding against moon germs

To prevent contamination on Earth with lunar pathogens, the crew was kept in a Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) for three weeks. The unit, constructed from a 35-foot aluminum Airstream trailer, was designed by Melpar Inc. and contained living and sleeping quarters, a kitchen and a bathroom.

It also featured communication equipment so the returned crew could speak to their families and to President Richard Nixon, who was on board the USS Hornet to welcome them back to Earth.

Eventually, it was determined there were no living organisms on the moon, and the quarantine procedure against ‘space germs’ was discontinued after Apollo 14.

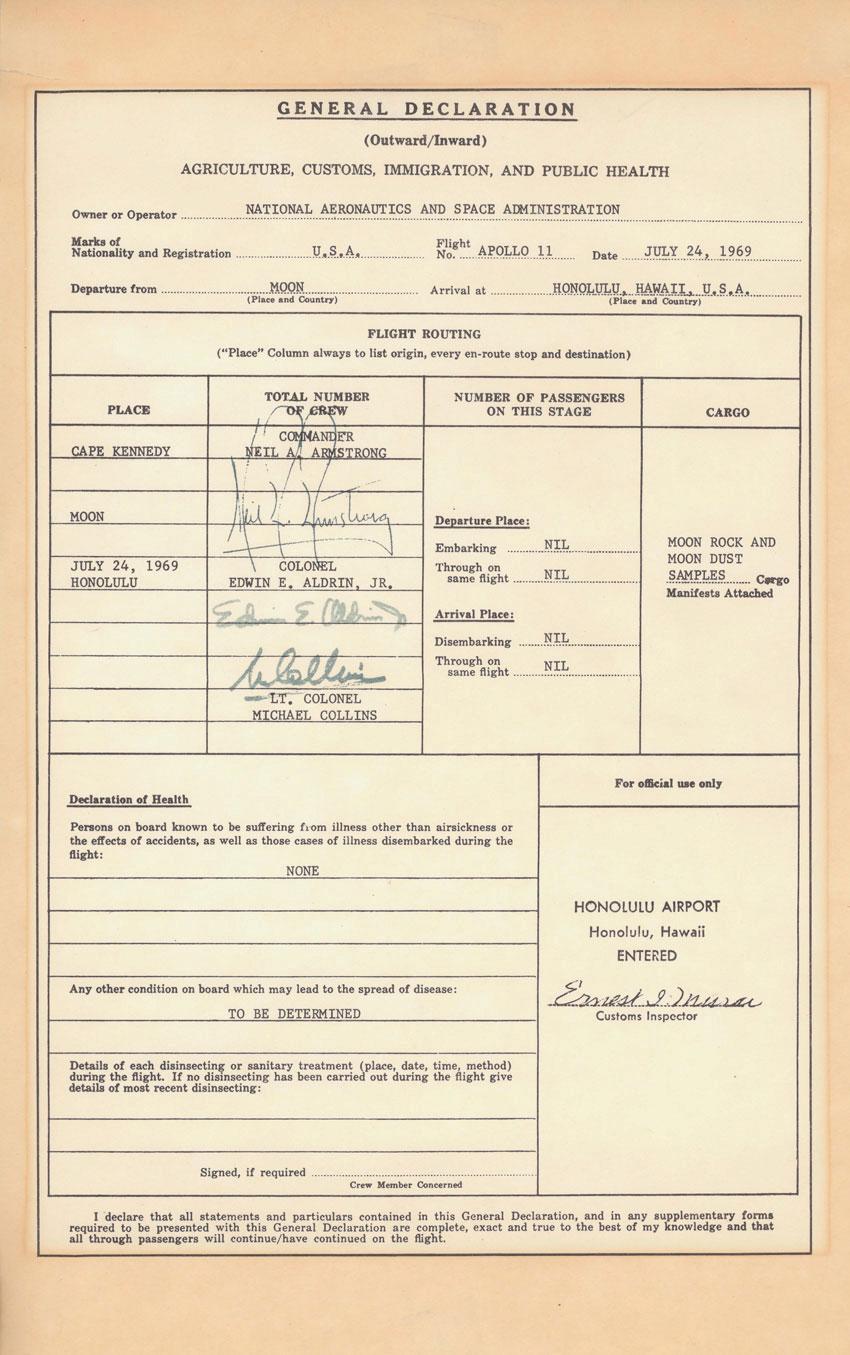

9. Anything to declare?

Upon arrival in Honolulu after their extraterrestrial travels, the Apollo 11 crew jokingly filled out a customs and immigration form. Among the items declared: “moon rock and moon dust samples.”

When asked if they had any conditions on board which could lead to the spread of disease, they filled in: “To be determined.”

10. Television history

Some 650 million people worldwide watched the telecast of the moon landing, and it was the most-watched television event in the US up to that date.

Armstrong deployed a single TV camera 30 feet away from the lunar module for the transmission to Earth, sending back black-and-white images of himself and Aldrin bouncing around on the lunar surface.

According to NASA, the data rate for the entire broadcast was 51.2 kilobits per second — slower than a 56K dial-up modem.

11. Nixon’s contingency speech

President Richard Nixon had a speech prepared in case Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin didn’t make it off the moon, underscoring the dangers of the historic first mission. Speechwriter William Safire suggested the president telephone the widows to offer his condolences before a speech, in which Safire crafted this opening line: “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.”

The prepared address also praised the duo who “know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.”

In the memo, Safire also suggested that after NASA ended communication with the astronauts, a clergyman ought to commend “their souls ‘to the deepest of the deep'” and recite the Lord’s Prayer.

12. Global Celebrities

After their return to Earth, the crew embarked on a global goodwill tour aboard Air Force II to 27 cities, in 24 countries, in 45 days, which included a ticker tape parade down Broadway in New York City, stops in far-flung Japan, Mexico, Pakistan, the Canary Islands, the Congo and Iran, and meetings with the pope, royalty and dignitaries.