Failing and forgotten: Black students languish as a Mississippi town reckons with its painful past

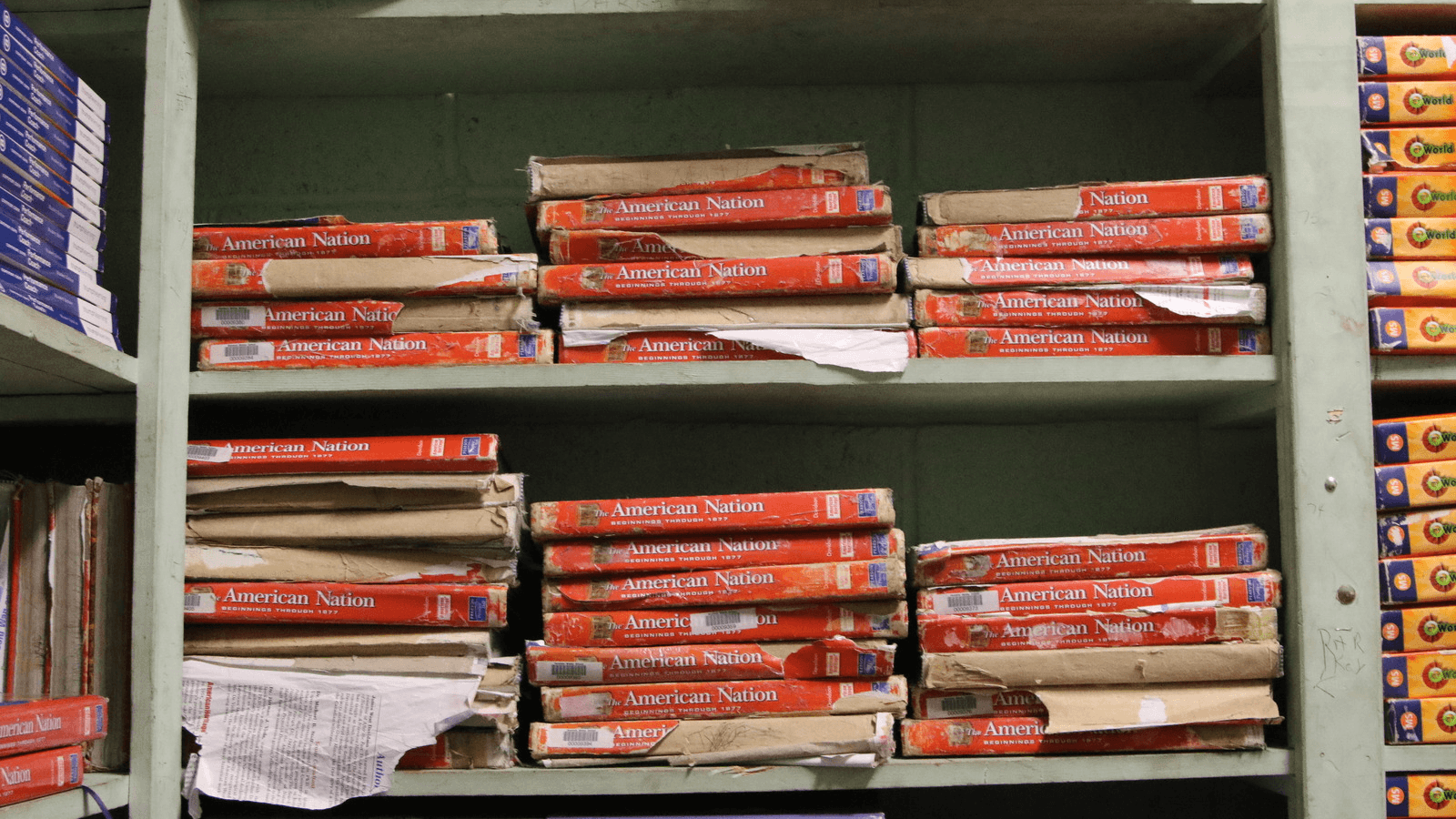

Tattered textbooks await students at the Yazoo City Municipal School District.

Sharonique Freeman’s teachers at Webster Elementary School kept quitting.

Freeman cycled through so many instructors and uncertified substitutes that her parents, Joe and Sharon Freeman, decided to ditch the Yazoo City Municipal School District after two years and homeschool her.

“We couldn’t jeopardize her education,” Joe Freeman said of Sharonique, who is now in eighth grade.

But most other parents in Yazoo City don’t have the income or the flexibility to educate their children at home or to enroll them in private school. So the students attend public school in a district that ranks near the bottom of the list in almost every measure of academic performance in the state — a state ranked dead last in the US in terms of education quality.

Editor’s note: This story is part of the Center for Public Integrity’s “Abandoned in America” series, which profiles communities connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when President Donald Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success.” Part I: How ‘The Wall’ could kill a Texas city Part II: ‘Hope to hopelessness’: Will government step up after second storm? Part III: What stands in the way of Native American voters? Part IV: High-speed rail could transform Fresno’s poorest neighborhood. Will Trump get on the train? Part V: St. Louis’ poorest residents ask: Why can’t our houses be homes?

After the federal government forced integration of schools there in the fall of 1969, white people fled Yazoo City in west-central Mississippi for the surrounding county and private academies.

They left behind a legacy of hatred and a school district that today is 98 percent black and has the lowest median income in the state.

Yazoo City Municipal School District is one of the many school systems in Mississippi that have re-segregated in recent decades — 49 of 145 districts are more than three-quarters black and 19 districts are more than three-quarters white.

And Yazoo City’s district is part of a startling pattern, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis.

None of the districts that are more than three-quarters black are rated “A” or “B” on the Mississippi Department of Education’s academic performance scale.

None of the districts that are more than three-quarters white are rated “D” or “F.”

“We still have a separate and unequal school system, which I certainly attribute to the fact that Mississippi has never tried to restore the educational opportunity that it deprived to generation upon generation of African American citizens,” said Jake McGraw, public policy director at the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation in Jackson, Mississippi.

Year after year, hundreds of black students in Mississippi’s segregated schools slip into adulthood without the skills they need to compete for jobs. The unemployment rate among the state’s black residents was 14.8 percent in 2016, compared to 6.5 percent for white residents, according to US Census Bureau data.

Twenty-seven percent of black people in Yazoo City were unemployed that year.

Sidebar: Race relations in Yazoo City, Mississippi: A brief history — To understand how Yazoo City got to where it is today, you have to look to a past scarred by centuries of abuses of one race against another.

The Center for Public Integrity, in its “Abandoned in America” series, is examining Yazoo City and five other communities connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success” — and a critical midterm election looms.

Yazoo City’s plight doesn’t appear likely to change anytime soon, despite what may happen in the November midterm elections when Democrats will seek to wrest control of Congress from Republicans.

Yazoo City’s congressman, Rep. Bennie G. Thompson, D-Miss., is about to coast to a 14th term, facing only token opposition and no Republican competitor — one of the few congressional districts in the nation not to field a GOP candidate. But during his 25 years in the US House of Representatives, Thompson has only sponsored two bills related to K-12 education, neither of which passed.

Yazoo City could have a prime seat at the political table, but it won’t be easy without significant turnout from black voters in November. Mike Espy, one of the candidates in the Mississippi special election to replace retired Sen. Thad Cochran, is an African American and former Democratic congressman who hails from Yazoo City. But he faces stiff competition in a state that hasn’t elected a Democratic senator since 1982 or a black senator since Reconstruction.

The federal government, which forced schools to integrate decades ago, hasn’t intervened in recent years — and its courts are allowing districts across the country to wriggle out from under desegregation orders.

At the same time, President Donald Trump and his education secretary, Betsy DeVos, are pushing “school choice” policies, which would allow federal taxpayer dollars to be spent at private or charter schools — a move many conservatives hail as an elixir for failing public facilities, but the American Federation of Teachers says would “destabilize our public schools” and propagate segregation.

“The federal government, more so than not, actually seems to be complicit in the resegregating of American schools, particularly in the Deep South,” said Leslie Hinkson, assistant professor of sociology at Georgetown University, who has studied the achievement gap between black and white children since 2001.

Studies disagree about whether integration has worked or whether it hasn’t, but what’s generally accepted across academia is that schools with a high concentration of low-income students don’t adequately prepare children for adulthood.

In Mississippi, race and income are inextricably linked. Black people made up 38 percent of the population in 2017, but they accounted for 60 percent of people in poverty there, according to the US Census Bureau.

The people in Yazoo City lack the resources to attract the attention of politicians with campaign contributions — they gave $193,600 to federal political races in the 2016 election cycle, but more than half of that came from the family of former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour, a Yazoo City native and Republican. Half the voting-age residents in Yazoo County do not vote, one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the nation, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of Census Bureau and OpenElections data.

A federal lawsuit filed in 2017 by the Southern Poverty Law Center aims to force Mississippi to bridge the academic gap between the state’s white and black schools. Two of its four plaintiffs are low-income mothers living in Yazoo City, a small town known as the “gateway” to the Mississippi Delta, about 40 miles north of Jackson, the state capital.

But the court case likely will take years to move through the system. And the state legislature hasn’t been able to redesign a school funding structure that, advocates say, has done little in the past couple decades to prop up poor districts like the one in Yazoo City.

Whatever hope African Americans may have had 64 years ago, when the Supreme Court outlawed “separate but equal” school systems in Brown v. Board of Education, has faded.

“We tried with desegregation, and it failed,” said Yazoo City Alderman Aubrey Brent Jr., who graduated from the all-black high school there in the 1960s. “Where do we go from here?”

Local frustration

On a sweltering July afternoon inside Webster Elementary School, the oldest facility in use as a school by the district, an “out of order” sign hung on one of the bathroom stalls. Desks were marred from years of use. In the former all-black high school across town, which is still used by the district today, some of the windows in the classrooms were cracked. Paint was peeling in the hallways.

Webster’s heating system went out a few years ago and parents tried to give the school money to fix it, said a parent who declined to be named because he feared retaliation against his child. Last year, a cold snap hit Yazoo City and the school heaters couldn’t keep up, so the teachers huddled the kids together in one room for warmth, the parent said. He picked his student up in the middle of the day, and they left.

The Southern Poverty Law Center’s lawsuit against Mississippi alleges parents have had to send toilet paper and hand sanitizer to Webster with their children because the school has run out in the past. (The district’s administration said that’s not true.) The lawsuit also alleges bathrooms at Webster don’t always work and that textbooks and technology are outdated.

Studies show students in run-down buildings tend to perform worse on tests than those in modern facilities.

In Yazoo City, poor student performance is endemic. Carolyn Johnson, a former 4th-grade teacher there, said many of her students couldn’t read, which meant they couldn’t do their math, science or social studies assignments.

Johnson said her classroom was rife with discipline problems, and she didn’t feel like she had the backing of her administrators when children acted out to the point that they disrupted entire classrooms.

Fed up, Johnson left the Yazoo City district in February, cashed in her retirement savings after 40 years as an educator and used the money to start the Yazoo Gifted Academy for preschool children.

She aims to raise a crop of readers by exposing kids to books early and by teaching their parents how to nurture readers at home.

But even if she’s successful, her inaugural class of 22 will represent a tiny fraction of the school district’s 2,400 children.

Tracie Britten was a 4th-grade math teacher at Yazoo City’s McCoy Elementary School for two years, but left as part of an exodus of teachers this past year who were unhappy with the way the school was being run, she said. She took a job teaching in Canton, Mississippi, a half-hour drive from her home.

A school absent teachers is only a building. In early July, the Yazoo City district was advertising to fill 24 vacancies at McCoy, which teaches children in 2nd through 5th grades. There were 11 vacancies at Webster Elementary, which serves pre-K, kindergarten and 1st graders; 11 vacancies at the high school; and 14 jobs posted for the middle school.

Yazoo City schools continue, by most every other measure, to falter.

Yazoo City’s teachers are paid less than the state average and they have more students in their classrooms, according to Mississippi Department of Education data.

The district is ranked 2nd lowest in terms of the share of students deemed ready for college or careers — only 5.6 percent of students met the criteria. Its graduation rate is 66.7 percent, tied for the worst in the state.

In a school district of 2,400 children, only 12.2 percent of Yazoo City students were considered proficient in reading by the state in 2018 — the second lowest rate in the state — and 14.4 percent were considered proficient in math — the sixth lowest rate.

About a quarter of its students were paddled for bad behavior in 2015.

Nearly a third of Yazoo City’s high school students are chronically absent.

Yazoo City spent about $8,000 per student in the 2016-2017 school year, well below the state average of $9,781 per student. It was ranked 145th out of 147 school districts that year for spending per child, yet studies show students from low-income families need more support and resources at school than students from wealthy families.

For a school district seemingly incapable of helping itself, where can help be found?

State inaction and a revolving door

In 2013, the Mississippi Department of Education decided an “extreme emergency exists” in the Yazoo City Municipal School District and considered taking control — a measure reserved for the worst performing school districts in the state.

The prognosis was grim: The state’s Commission on School Accreditation “found that the situation jeopardized the educational interests of the children enrolled in the District schools,” and without state intervention, “there would be a continuation of an inadequate and unstable educational environment thereby denying the students of the District the opportunity to learn, to excel and to obtain a free and appropriate public education,” according to a 2013 agreement signed by state and district officials.

At the time, Yazoo City’s then-incoming superintendent presented an ambitious improvement plan, and the state concluded it lacked the resources to take over control — it was assuming control of two other districts at the time, said Mike Kent, interim deputy superintendent for the state education department.

Local Yazoo City officials continued running the district. Their plan never came to fruition because the superintendent left, Kent said.

State officials have been watching the district, just as they do all the poorest-performing districts, but there haven’t been enough resources to take over control, Kent said.

The state’s education department actually has a mandate from the Mississippi legislature to intervene.

Lawmakers passed a bill in 2016 that requires districts rated an “F” for two consecutive years or two out of three years to be absorbed by the state into a statewide “Achievement School District.” To resume local control, districts have to be ranked with a “C” or better for five consecutive years. The plan hasn’t been implemented, though, Kent said.

“We have been unable to, at this point, to actually set it in place, set it in motion because we haven’t been able to identify the personnel,” Kent said. “Sometimes we identify people to do the work, and you can’t pay them what they’re demanding.”

Under a separate 2017 law, the district could be labeled a “District of Transformation” and taken over by the state, but that hasn’t happened for Yazoo City.

Yazoo City has recently shown glimmers of improvement. For one, it moved from an “F” on the state’s scale in 2016 to a “D” in 2017.

But cause for optimism proved fleeting: Yazoo City reverted to an “F” when the new ratings came out earlier this month.

Adding to the angst is uncertainty at the top of the organizational chart.

The new superintendent, Georgia Ingram, was appointed in July to serve on an interim basis after the last superintendent quit two years into his three-year contract.

Ingram is the third superintendent in four years.

The district has had “academic challenges,” Ingram said. “Our biggest challenge this year is to make education a priority in our community, so people understand that our high school is the flagship for the community. If our high school is successful, that makes businesses and industries want to come into our community, and if our community is successful then there’s more money for the school district.”

She acknowledges the challenge ahead of her.

The Yazoo City school district’s median household income is $20,000 a year — the poorest school district in the state.

“If you don’t have good schools, you don’t have good minds, you don’t have innovation, you don’t have capability, you don’t have skills,” Yazoo City Mayor Diane Delaware said. “I don’t know the answer. I know it has to be fixed. And I believe it can be fixed.”

Hinkson, the assistant professor of sociology at Georgetown University, who has studied the achievement gap between black and white children, said the federal government could step in — drastically altering district boundary lines to blend black and white students, or pumping more money into low-income, segregated schools.

That would allow schools to retain qualified teachers, build nicer facilities and offer more advanced placement courses and extracurricular activities.

“If those schools with that greater funding can significantly improve their quality, the question is: Should we care whether or not white parents want their kids in those schools?” Hinkson said.

Such federal intervention isn’t likely. Trump and DeVos see a different solution to the problem.

Rather than inject troubled schools with federal dollars, they see “school choice” as a way to give students in poor-performing districts a chance to get into better schools. Trump, who has held three rallies in Mississippi — including one in Jackson — since he first began his race for president in June 2015, has said education is the “civil rights issue of our time.”

“I am calling upon members of both parties to pass an education bill that funds school choice for disadvantaged youth, including millions of African American and Latino children,” Trump said in 2017. “These families should be free to choose the public, private, charter, magnet, religious or home school that is right for them.”

Yazoo City itself doesn’t get a lot of presidential foot traffic. The last president who visited was Jimmy Carter in 1977, according to Mississippi Today.

The nearest district office for Thompson, Yazoo City’s congressman, is 40 miles away in Jackson.

Thompson has opposed “school choice” bills in the past, and he said he’s happily supported education bills proposed by congressional colleagues that invest more money into schools.

Of the two education-related bills Thompson has sponsored, one would have provided financial incentives to attract teachers to rural and high-poverty areas. He sponsored that bill in 2003. The other, sponsored in 2005, related to a preschool program for children affected by Hurricane Katrina.

Both languished and died, having never received a vote either by a House committee or the full House.

Thompson said local business leaders in Yazoo City haven’t asked him to sponsor bills related to improving the school system. They’re more interested in workforce development, he said.

“The majority, probably 90 percent or better, of the (members of) chambers of commerce and the rotary clubs, send their children to segregated, private academies in rural Mississippi, and in most instances in the South, that’s what you find,” Thompson said. “They have abandoned the public school system.”

The special Senate election to fill the seat of Sen. Thad Cochran, R-Mississippi, who retired earlier this year, will take place Nov. 6 and feature multiple candidates from both parties. If none of the candidates get more than 50 percent of the votes, the top two finishers will face each other in a Nov. 27 runoff.

Espy, who hails from Yazoo City, is a Democrat who served three terms in the US House and who was one of President Bill Clinton’s agriculture secretaries. Espy is facing Republican Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, who was appointed to finish Cochran’s term until the election and is close in polls, and Chris McDaniel, a tea party-backed Republican who has defended Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Facebook posts and who uses Confederate symbols on his campaign signs.

None of the candidates responded to requests for interviews.

According to her website, Hyde-Smith believes “Mississippi does not need Washington telling it how to raise and educate its children.”

Pointing fingers

Local politicians and business leaders said it’s hard to attract businesses to Yazoo City because of the poor-performing schools. Brent, the alderman, said it took 20 years to get Walmart to move in before it opened a store in recent years.

Walmart aside, Delaware said she’s had no major economic development announcements to make.

The federal prison on the outskirts of town is one of the largest employers, but many of its workers live out of town and commute to Yazoo City every day, residents said.

“We’d like to have those people living here, but they don’t want to come into an area with a failing school system,” said Thomas Johnson, owner of Tom’s on Main, one of the few restaurants in downtown Yazoo City. “Certainly that’s going to affect the economy. If we had a good school system, I think our economy would be much better.”

Johnson, who is white, served in the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1992 to 2000, and he sat on the education committee that was responsible for crafting the school funding formula that’s still in place today. Johnson’s wife is a retired school teacher.

To him, the problems facing failing school systems like Yazoo City’s harken back to a lack of involvement from parents and absentee fathers — not the funding structure.

Brent, who is black and who graduated from the local school district when segregation was a way of law, not just life, agrees that there are cultural barriers to education to an extent.

Some blacks are discouraged from advancing themselves through education, he said. But the problems go deeper than that, said Brent, who was an educator for 42 years.

There aren’t enough black role models for children to look up to, he said, thanks to the cycle of poverty and a system that replaced successful black teachers with white instructors when schools were integrated. Teachers are underpaid, and it’s hard to get them to commit to staying in problem schools. And it’s hard to raise enough money for the school system when the funding structure is based off of taxing dilapidated structures.

“The cards are stacked against poor communities,” Brent said.

Johnny Staples, who coached basketball, football and tennis in Yazoo City from 1968 until he retired 12 years ago, said the students there need extra attention to help them succeed, which he’s tried to provide over the years through a nonprofit he founded called Focus on the Children.

He also points toward a loss of heritage that black children endured when the schools integrated. They were no longer learning through plays and singing and dancing, he said.

“When we integrated, all of that went out the window, and it was a whole different ballgame,” Staples said.

And school leadership has been in constant tumult, Staples said. Over the years, the superintendents have been largely ineffective — and the ones who knew what they were doing were hamstrung by the school board.

Ingram, the current interim superintendent, said the schools are constantly playing catch-up as the state changes its accountability system. Ingram has been an educator for 30 years; since joining Yazoo City schools in 1991, she’s been a teacher, a principal, school improvement director, director of testing and curriculum and director of child nutrition.

“Every time we have gotten used to doing things one way, the state changes how they want it done,” Ingram said. “They change how they grade us, they change the accountability level, they change the accountability system.”

Delaware, the mayor, said the district should stop blaming the accountability system and take a cue from the private sector, where she worked for many years: invest money where the problems are and be willing to adopt methods that work elsewhere in the industry.

Delaware said she toured a school in Chicago that had adapted to the needs of the inner-city children it was serving. But when she brought some of the ideas home to Yazoo City, they were dismissed as outside ideas that would never work in a small town.

“We are our own worst enemy,” Delaware said.

Moving forward

Ingram, the interim superintendent, says she plans to focus on improving teacher morale and student achievement this year. She also hopes to encourage the community to put more emphasis on education.

But some people believe it will take more to make a significant difference.

Thompson said he believes the federal government should take more of a proactive role.

“We have not provided a level playing field to the children who attend public schools because we have taken our hands off,” Thompson said. “That’s the government’s attitude toward public education. There has never really been a real stomach at the Department of Education or Department of Justice to pursue what some of us believe is constitutional guarantee to a free and equal education.”

Delaware and others have doubts that Trump’s administration, including DeVos, have any idea what it’s like attending school in rural black America.

“This was within a lot of people’s minds,” said Jacob Sheriff, Yazoo County’s aptly named sheriff, who is black. Trump’s slogan was “making America great again. A lot of people were saying, ‘Are you really saying that? Do you really mean it, or are you talking about making America white again?’”

The Department of Education did not respond to a list of questions sent from the Center for Public Integrity.

Each state has the authority to determine how much money will be spent on schools and how it will be divvied up.

In Mississippi, the current funding structure was approved by the legislature in 1997 and it was amended in 2006. The formula gives school districts a 5 percent bump in funding for each low-income student enrolled — which research shows is not nearly enough to meet the educational needs of students living in low-income homes and communities, said McGraw of the Winter Institute.

Lawmakers commissioned a study in recent years by consultants, who called for a new formula that would provide a 25 percent boost to districts for each low-income student enrolled, but it would have reduced the number of students qualified for the financial bump. Regardless, the legislature hasn’t been able to pass any bills that would adopt the consultants’ recommendations, McGraw said.

The lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center calls on the state to provide more of an equal playing field for schools around the state, but it faced a major setback earlier this year when a judge decided the state couldn’t be sued. The nonprofit has asked him to reconsider.

Even if he does, it will likely take years to resolve the case. For the foreseeable future, Yazoo City and other school districts around the state will remain segregated.

“There are several examples of schools and school districts that have successfully integrated and preserved integration,” McGraw said. “Where we see segregation, we see the continuation of all of the things that keep Mississippi 50th in education and wealth and health and everything else across the board.”

Joe and Sharon Freeman, the parents who educate their daughter, Sharonique, at home, have no plans to send her back to Yazoo City public schools.

“She needs to be at the top of her game,” Joe Freeman said.

Sharonique is getting all A’s on her report card. She wants to become a doctor and has her eyes on Harvard.

Joe Yerardi contributed to this report.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?