How ‘The Wall’ could kill a Texas city

US Border Patrol agents watch a gap in the border fence by the Mexico-US border near Brownsville, Texas, April 12, 2018. As President Donald Trump’s administration fights to fund a new, multibillion-dollar border wall, government lawyers are still settling claims with Texas landowners over the fence Congress approved more than a decade ago.

Molly Ferguson was 14 when she met Miguel Rodríguez Vásquez at a quinceañera in Mexico. Ferguson isn’t from Mexico — she’s lived in Presidio, a small Texas border town, all her life. And for Ferguson, that means she’s essentially lived her whole life in Ojinaga as well, the Mexican city right across the shimmery green-brown Rio Grande.

That night, at the quinceañera in Ojinaga, Rodríguez asked her to dance, and this year, nearly a decade later on a warm July evening, they married.

It might seem remarkable that their eight-year-long relationship spanned an international divide, especially given that Rodríguez’s immigration status has prevented him from ever entering Ferguson’s city. But for many in Ojinaga and Presidio, crossing the border is common. Ferguson doesn’t see Presidio and Ojinaga as cities in separate countries — no one in Presidio really does. Presidio feels more like an extension of Ojinaga.

Editor’s note: This story is part of the Center for Public Integrity’s “Abandoned in America” series, which profiles communities connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when President Donald Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success.”

“I guess I cross to a different country every day, but I really don’t see it as a different country,” Molly Ferguson said. “I consider it to be my home, too.”

The two towns only have each other. Around them, it’s miles of nothing, just dry heat, low shrubs, spiky cacti and the occasional dust devil, framed by the foothills of the Sierra de la Santa Cruz mountains.

And yet, politicians in Washington, DC, talk of building a wall between the communities. Donald Trump rooted his presidency in this idea: that the border is awash in criminals and drugs, and the US needs a physical barrier for its own protection. Trump this summer threatened to shut down the federal government in the fall if Congress fails to authorize construction of a wall.

“If we don’t get border security after many, many years of talk within the United States, I would have no problem doing a shutdown,” Trump said. “We’re the laughingstock of the world.”

The US Senate passed a short-term spending bill on Sept. 16 — and Trump signed it shortly thereafter — to keep the government running through Dec. 7, postponing a fight over funding for the border wall until after the midterm elections.

Presidio is one of six communities the Center for Public Integrity is profiling this month on the eve of a critical midterm election that will decide the balance of power in Washington. These communities are connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success.”

There are certainly some towns along the US-Mexico line that face an influx of illegal border crossings and related criminality. But Presidio is different. Numerous residents feel Trump’s wall talk excludes them entirely, including Molly Ferguson’s father, John — he’s the mayor of Presidio. John Ferguson said the Trump administration’s keep-Mexicans-in-Mexico rhetoric is vastly out of touch with what his town needs.

Because in Presidio, most people don’t want a wall — the tiny, impoverished town has far more to worry about, like the lack of a nearby hospital and new tariffs that could destroy their only hope for economic viability. And they don’t need a wall like other border communities might. Crime is low, illegal border crossings appear relatively few in number and residents cherish and rely on their relationship with the community across the river. A wall wouldn’t just be an ugly blot on the south end of Presidio; it would be a mortal wound, a slice through a living, breathing organism — a community and culture that doesn’t end when it hits the border — it would cut people in Presidio off from a culture to which they belong.

“The solution absolutely is not to just build a wall. That does not address the problem. It just puts it out of our sight. The United States doesn’t have to look at it anymore. How arrogant,” John Ferguson said. “Who told you we needed a wall? We didn’t tell you that. And we’re the ones that live here.”

‘One big city’

If the cities are sisters, with interwoven cultures and histories, Presidio is the neglected, under-loved sibling.

The city, with a population a bit over 4,000, is all browns, burnt oranges and gray-yellows — the duller, drabber of the two cities, far smaller, quieter and more empty. Ojinaga, about seven times bigger, with a population of about 28,000, is vibrant and bustling — it boasts more grocery stores, dentists, doctors, restaurants and bars than Presidio could ever hope to have, and so on weekends, Presidio experiences a mass exodus. Houses empty and families pile into cars and shuttle toward the international bridge. The streets become even emptier than they are on weekdays.

Ojinaga is cheaper and has more options: fruits and vegetables that aren’t wilted, eggs and milk with lower price tags. “And it takes us what, three minutes to cross? So why not?” says Norma Escontrias, an elementary school teacher in Presidio.

Beyond the amenities Ojinaga provides Presidio residents, it’s home to aunts, brothers, parents and grandparents. Ojinaga isn’t just where Liz Rohana, who works at the Presidio-Brewster County Indigent Healthcare Program, goes to have her dental work done; it’s where her mom was born and where her grandma lives and where her vast extended family congregates each weekend for coffee and pound cake.

“Presidio is the sort of town that most Texans will never see and wouldn’t understand if they did. So little do its location, climate, economy, and culture fit the patterns of America that it is more realistically regarded as a suburb of Mexico than as a village in Texas,” Dick Reavis wrote in a Texas Monthly article in October 1983. It seems little has changed since then.

On stormy nights when Presidio loses electricity, the city of Ojinaga will lend Presidio power. When Ojinaga’s landfill caught fire, Presidio’s volunteer fire department rushed across the Rio Grande to assist. The two cities aren’t just linked by the general goodwill of their communities — they’ve signed agreements for mutual cooperation to respond to threats to public health and safety.

“We’re literally one big city divided by a river,” Presidio City Councilwoman Isela Nunez said.

Physical tributes to the connectivity of the cities can be found on both sides of the border. In a building lining La Plaza, an open square by Ojinaga’s city hall, there’s a mural on the second level: two birds on either side of a door, facing each other, wings spread as if in welcome, painted in bold streaks of white, black and brown. The mural, created by Miguel Valverde and commissioned by the city of Ojinaga, represents the two communities on either side of the US-Mexico border with a doorway between them.

On the Presidio side, a 100-foot-high city water tower pokes into the sky. It, too, is outfitted with an enormous mural, depicting a woman who immigrated from Mexico more than 30 years ago and now has a store where she sells used clothing in Presidio. The mural was a gift from the Mexican government to the city — painted earlier this year — as a gesture of bi-national goodwill and cooperation amid a time of harsh rhetoric on immigration issues at the national level.

But for Presidio’s city administrator, Jose Portillo, the well-intentioned mural is also a reminder of the divisive arguments in Washington, DC, about immigration policy and border security. Although Presidio consistently and overwhelmingly votes Democratic, he and other local officials strive to work well with any politician, no matter their party, including their Republican Rep. Will Hurd, to get whatever access to federal help they can. Hurd’s Democratic opponent, Gina Ortiz Jones, is getting significant backing from the Democratic Party as it tries to take over Congress, and while the cluster of potential votes in Presidio is small, and many potential voters often stay home, those who do vote are reliable and potentially important.

Ortiz Jones has visited the city of Presidio at least twice while campaigning over the last eight months. Hurd hasn’t visited the city once in that same span of time, though Connor Pfeiffer, a spokesman for Hurd’s campaign, said praise for Hurd’s work by local city and county officials speaks for itself.

“Will Hurd has done some very helpful things for Presidio, there is no denying that. Personally, I don’t know, I have problems with his voting record in Congress, but where the rubber meets the road, he’s shown himself,” John Ferguson said.

Notable projects Hurd’s office has worked on in the county include improvements to the Presidio port of entry, the Presidio rail bridge that handles cross-border rail traffic, and worked to pass legislation to create public-private partnerships at ports of entry to invest in infrastructure, Pfeiffer said in an email.

Ortiz Jones said, however, that Hurd’s approach to immigration fronts as moderate, but is “kind of like someone set your house on fire and showed up with a pail of water at the end,” she said. She cites his weak commitment to programs like the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, an immigration policy that shields some undocumented young adults from deportation.

She said the biggest issue she sees in the district is access to health care. “People are fearful they are not going to be able to afford it in the near future or they physically can’t get to it,” Ortiz Jones said.

She said Hurd has dropped the ball on health care access and affordability.

“When I talk to people not in the district it always surprises them that our one issue is not immigration,” she said. “Like, no no no. Immigration is not the issue — health care is the issue. It’s interesting how some of these issues playing out in our backyard are getting a lot of national attention.”

Democrat, Republican, whatever. Party politics are useless, Portillo says, and participating in endless drivel about immigration policy isn’t going to fix anything in Presidio. Presidio doesn’t even have political pull in Austin, Texas’ state capital, so why would it have access on Capitol Hill or in the White House?

“We’re not big enough to say Will Hurd’s not our party guy, he’s not our ticket — everybody else can do that, senators can do that, [House Minority Leader Nancy] Pelosi can do that with Trump, they can do that to each other, we can’t do that. We can’t afford to,” Portillo said. “We’re going to work with whoever’s in office, and we’re going to tell them what our needs are.”

All Portillo can do is “let politics be politics” while he works tirelessly to ensure his tiny part of the world, Presidio, has what it needs.

And its needs are many.

What Presidio needs instead of a wall

A group of women flipped tortillas and scooped brisket from pots as the inescapable summer sun beat down on a Saturday afternoon. A small line assembled. Cash and paper plates laden with warm food changed hands. The money was meant for Billy Hernandez, a Presidio resident who had lung problems and was making regular trips to Midland, Texas, for checkups. For having medical issues, Hernandez is lucky: He works for the county government and therefore has health insurance, unlike the 44 percent of Presidio residents who lack it, according to the US Census Bureau.

Still, the costs of traveling to and from Midland for medical care are steep. While temporary doctors staff two medical clinics within city limits five days a week, the nearest hospital of any size is in Alpine, Texas, 87 miles away. The closest health specialists (and bigger hospitals) are in El Paso and Midland-Odessa — both four-hour drives away.

Because of the distance between Presidio and comprehensive American medical care, everything from a minor checkup to a life-threatening surgery becomes a big deal. One must coordinate travel, hotel rooms, meals. It all amounts to a tremendous expense for a family to bear, especially considering census data show the median household income in Presidio is $24,767.

So, for many people in Presidio, Mexico is a lifesaver, sometimes literally. Karmina Proano, who works the cash register at a family-owned furniture store in downtown Presidio, doesn’t have health care and had her surgeries in Mexico — gallbladder, kidney stones and an emergency hysterectomy a year ago.

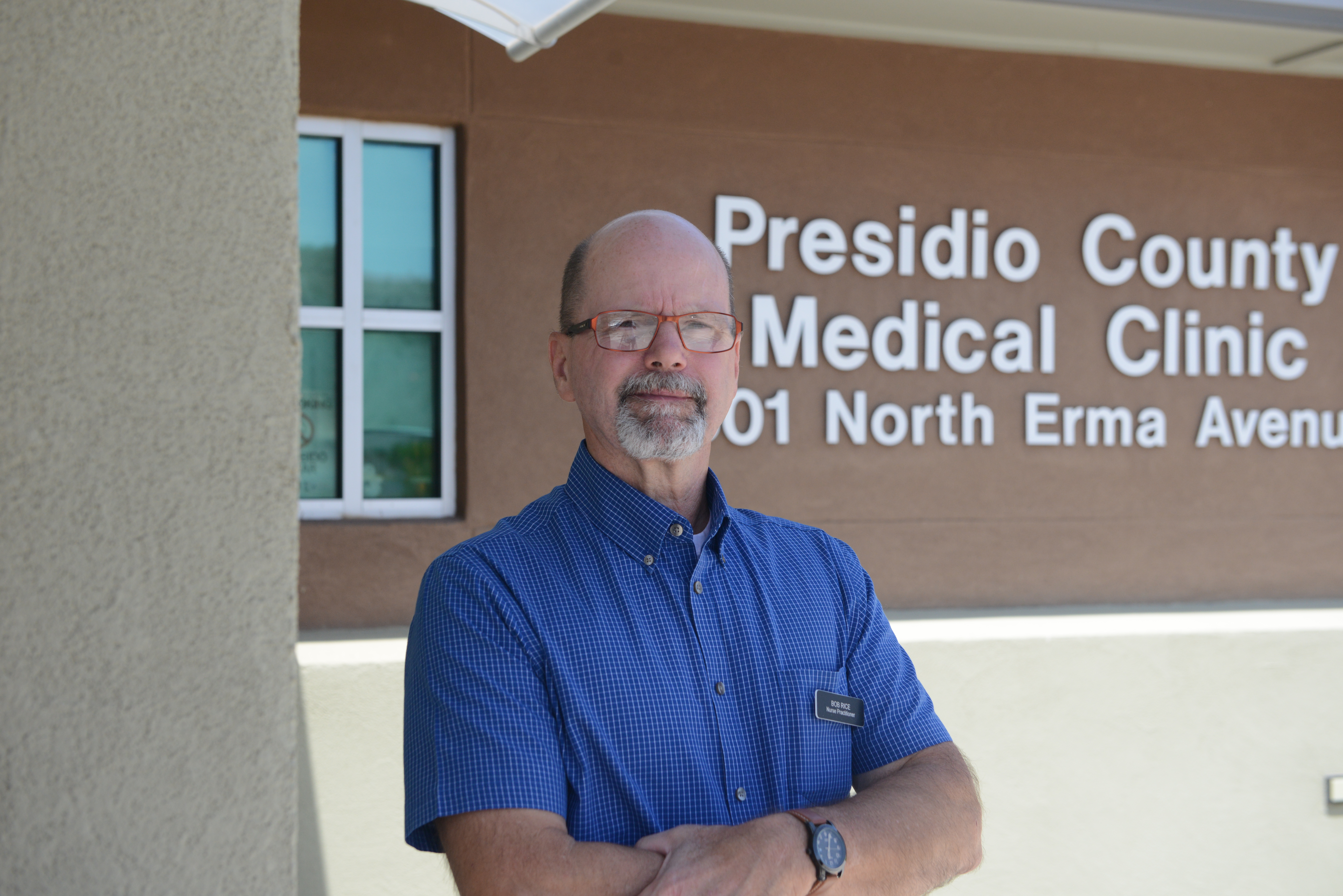

Chronic infrastructure problems make steady care near impossible in the clinics Presidio does have, said Presidio resident and nurse practitioner Robert Rice. On a Thursday afternoon in July, the water system shut down for hours. A few weeks before that a bad storm caused the whole area to lose electricity for over three hours. The clinic had to buy a generator to help keep vaccines in the correct temperature range.

For emergency medical care, where a long drive in a personal vehicle isn’t viable, residents either have to rush across the border to the hospital in Ojinaga or call an ambulance or airlift to Alpine. With only one ambulance, wait times for emergency care are sometimes six to eight hours long, and the city incurs incredible costs just to run the one ambulance it has. EMS services account for more than a fifth of the city’s puny, approximately $4 million budget.

The consequences can be fatal. Nearly everyone in the small town seems to know someone or know of someone who died because they couldn’t get to a hospital in time.

Presidio indeed lacks basic, functioning infrastructure: Water pump breaks and power burnouts are frequent, the town’s financial management is strained, and beyond the school district and border patrol activity, its economy is moribund, the city government’s revenue stream at drought stage. It doesn’t help that city officials discovered several years ago that Presidio’s aging water system has difficulty pumping uphill, and hundreds of water meters across the city were inaccurate, causing the city to lose at least 10 percent of its water sales revenue. This year, the city dipped into its general fund to pay the Internal Revenue Service more than $800,000 in back taxes and penalties incurred from 2013 to 2016 because of poor administrative oversight, The Big Bend Sentinel reported.

Presidio has made some incremental improvements. In 2010, it installed a large battery system, one of the first and biggest of its kind, which reduced the frequency of its power outages. Presidio financed booster pumps for the water system and in 2016 bought and installed 400 water meters to replace aging and malfunctioning meters through a community development block grant. And local officials are in initial talks with Texas Tech University for a tentative plan to bring a “micro-hospital” to Presidio. Up until a few years ago, all the roads in Presidio were dirt — more accurately, trampled down dust. Now, a few main streets are paved.

Presidio’s bridge to Mexico is also being expanded, potentially creating new jobs. Local officials credit Hurd with helping Presidio secure a presidential permit (issued by the secretary of state for cross-border infrastructure) and for a $12 million project to widen the port of entry by two lanes in order to accommodate increased 18-wheeler traffic.

Currently, trade coming through Presidio is extremely low. Freight valued at about $18 million went through Presidio’s port of entry in June. Comparatively, $6.6 billion went through El Paso to the northwest and $454 million through Del Rio to the east.

Mexico, for its part, sees promise in the Ojinaga-Presidio border crossing. Nearly 500 miles of the US-Mexico border — more than one-fifth overall — stretch between the border crossings at Del Rio and El Paso, and Presidio is right in the middle of it, city economic development adviser Brad Newton points out. Mexico has made a huge investment in the Ojinaga-Presidio crossing: Mexico President Enrique Peña Nieto visited Ojinaga on Thanksgiving in 2013 and announced he was going to build a model port of entry there.

“Mexico is definitely gearing up to come through here. And so now, we’re gearing up to accept their traffic,” Newton said.

But tariffs imposed by the Trump administration on aluminum and steel have caused a new wave of worry. The biggest industrial player in Presidio is a cross-border maquiladora called Solitaire that manufactures mobile homes. (The large supply of inexpensive labor from Mexico — boosted by the North American Free Trade Agreement — spurred the rise of manufacturing plants along the border.) Solitaire uses a significant amount of steel and aluminum, and although it recently doubled its production, tariffs could potentially increase prices to the point where it cuts production, John Ferguson said.

“One thing we’ve been banking on for the past 30 years is to try and grow international commerce with Mexico, and all of a sudden you’ve got some trade tariffs that could put a damper on that,” John Ferguson said.

Even if the bridge expansion attracts more trade, Presidio almost certainly can’t accommodate it without state or federal assistance. It can barely support its own residents — during the holidays when families flow in, parking is scarce and Presidio’s two small hotels quickly book up — and opening businesses and expanding city infrastructure is a notoriously slow process, says Nunez, the city councilwoman. Her brother tried to construct a large office building in the area for their family company, but the land surveyor, which serves both Presidio and Marfa — a small city about an hour’s drive north — was busy. After a year, the land surveyor still hadn’t completed the required survey.

Presidio County is vast — at almost 4,000 square miles, it’s three times the size of Rhode Island — and so sparsely populated that local government resources that affect people’s daily lives are scarce.

There’s no Social Security office. The Department of Motor Vehicles is only open for half a day each week, on Wednesdays. The closest fully functioning county courthouse is in Marfa. Hurd periodically sends staffers to visit Presidio, but his closest permanent presence — a district congressional office in Fort Stockton — is 153 miles away.

Presidio’s public library has become a de facto help desk — a refuge of the cash poor. Carmen Elguezabel, Presidio’s library director, said people visit her for all sorts of problems: to apply for federal government benefits, to take driving tests. Farmers show up, too, to ask for help renewing their special equipment tags.

People often come to Elguezabel because they need help translating English into Spanish. Navigating government resources without English proficiency is difficult. An estimated half of Presidio residents speak English less than “very well,” according to census data, and a whopping 98.5 percent speak a language other than English at home.

It’s safe to assume that “other” language is usually Spanish: 92.9 percent of households speak Spanish. Not all Presidio residents, however, are primarily Spanish-speaking.

Presidio’s school system, which has embraced immigration to improve teacher retention in such a desolate, resource-poor area, has sponsored the visas of about 30 Filipino teachers, who have settled into a small, tight-knit community in the majority-Hispanic city.

Now, graduation rates are up. And the high school has a nationally recognized rocket and robotics team — just a few months ago, some of Presidio High School’s students embarked on a cross-country drive in a solar-powered car they built themselves.

The school supports a substantial “at-risk” migrant population of students that only temporarily live in Presidio with another family member, usually their mother or a grandparent, and enroll in the school while their fathers travel long distances to work on the oil rigs in Midland-Odessa, or on tomato farms in Marfa. Frequently, people move deeper into the state of Texas for jobs Presidio is unable to offer.

This transience is part of the reason Presidio’s political influence is so feeble.

Presidio County historically has one of the lowest voter turnouts in Texas. Residents making reportable campaign contributions gave about 29 cents per person to national-level politicians, parties and political groups during the 2016 election cycle. And low political participation is revealed to be even lower when one takes into account the swath of Presidio residents that are non-participants because of their citizenship status. Of Presidio’s recorded population of 4,051, more than a third, 1,427, are not US citizens, according to 2016 American Community Survey data.

In Washington, DC, money and votes talk, and many officials in the nation’s capital aren’t listening to what Presidio residents, poor in wealth and polling station participation, have to say for themselves.

The wall: What’s happening in Washington

In 2006, as part of the Bush-era Secure Fences Act, Congress proposed a six-mile long, 15-foot high border wall through Presidio, which city officials formally opposed.

The six miles of wall planned for Presidio in 2006 were never built, even though the federal government erected at least 650 miles elsewhere.

The decision was, in part, practical: the Presidio area is extremely remote and its illegal border crossing apprehension rate is consistently among the lowest on the southern border.

Trump has prioritized building a continuous border wall, and he has been increasingly frustrated with Congress’s failure to fund it. As Congress worked on an appropriations bill in the summer, some Senate Republicans quietly said Congress was unlikely to pass a funding bill that includes money for the wall, even as Trump threatens a government shutdown. They have been right so far. The Senate passed a spending bill on Sept. 16 — without funding for the wall — to tide the government over for the next couple of months. Estimates vary on how much a full, physical wall spanning the US-Mexico border would cost, but even the federal government’s most optimistic estimates peg it in the tens of billions of dollars. Annual maintenance is estimated in the hundreds of millions.

Hurd publicly opposes Trump’s plan to build a border wall and recognizes that Presidio may not need a physical wall. He represents a swing district that stretches hundreds of miles between El Paso and San Antonio, so it makes sense to sometimes ally himself with moderate Republicans and Democrats. For example, when an ice storm caused cancellations of flights to DC, Beto O’Rourke, the Democratic candidate running to unseat Sen. Ted Cruz, embarked on a road trip with Hurd and livestreamed their trek. O’Rourke has said he won’t endorse anyone in the race, including Hurd’s Democratic opponent, Ortiz Jones.

Neither O’Rourke nor Cruz responded to multiple requests for comment about Presidio.

Hurd alone has little power to stop Trump from demanding a border wall or preventing Congress from funding one. But he engages with Presidio and works to represent everyone regardless of whether they voted for him, Newton said. In August 2017, Hurd held court at The Bean Cafe in Presidio, one of the town’s three main restaurants, to discuss the challenges facing Customs and Border Patrol and a proposed “smart wall” — using sensor technology, instead of hulking concrete and metal, to defend against illegal border crossings. Several Presidio residents say a “virtual wall” is a suitable alternative, an indication that Presidio residents’ opinions on border security and immigration in general aren’t uniform.

Nunez says a completely open border would be devastating.

Apolonia Gonzales, who runs a thrift store in downtown and whose husband works for Customs and Border Patrol, says those who cross the border illegally into Presidio pose no threat and are usually just looking for food or water.

Molly Ferguson said it’s hard when people on the border can’t legally cross: They are part of the Presidio community. Her good friend’s mother was deported the year she graduated from high school.

Farmer Terry Bishop doesn’t necessarily want more people crossing the Rio Grande onto his land, which ends at the Mexican border. But a wall would block his access to river water for agriculture — and, he fears, cause severe environmental damage.

Most of them agree on Trump’s wall, though: It’d be intrusive and destructive to property — and the city’s relationship with Ojinaga.

***

In July, when Molly Ferguson donned her wedding dress — black, embroidered with yellow flowers and lined with white lace at the bottom in a traditional Oaxacan style — and married Miguel Rodríguez, she expected to start this next part of their relationship under the same roof, like most newlyweds.

But it’s never been that simple for them to navigate the border that splits their lives in two.

On their honeymoon in Veracruz, Mexico, Ferguson went to an evening concert with Rodríguez, where they listened to Son Jarocho — similar to mariachi, but with different instruments. Ferguson felt right at home — after all, she’s from Presidio, which draws its culture, its lifeblood, from the other side of the border, she says. She embodies the notion: Ferguson and her parents together perform in a mariachi band at weddings and parties on both sides of the border.

But Rodriguez is stuck on the Mexico side, and that means he couldn’t visit Ferguson while she was attending college an hour away in Alpine. He’s never come over to have dinner with her family at their home in Presidio.

“It feels really unnatural that, like, we have this boundary, even though we’re only five minutes away from each other. It’s really strange to think that a person — my husband — can’t visit me,” Molly Ferguson said. “Are you kidding me?”

They dream of life where Ojinaga and Presidio become even more symbiotic, unencumbered by government restrictions and certainly not divided by a wall. The relationship between these two cities, like Ferguson and Rodríguez’s own relationship, would grow stronger.

For now, this dream is on hold. Looming over them is the threat of an idea proposed in Washington, championed by people who represent Presidio but know little of their way of life.

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, DC. This story is part of the Center for Public Integrity’s “Abandoned in America” series, profiling communities connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when President Donald Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success.”