Teen ‘boys will be boys’: A brief history

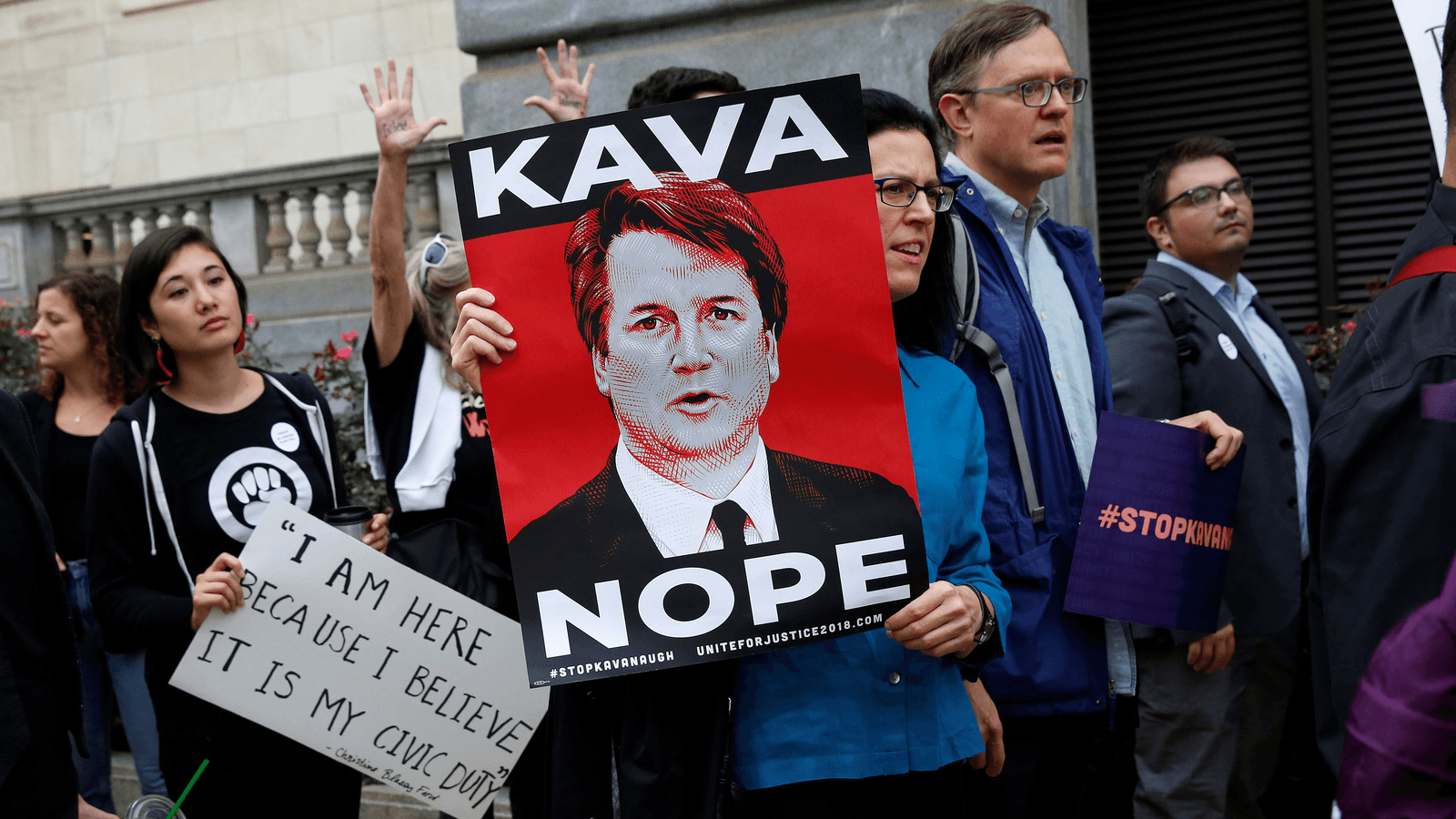

Protesters rally before a hearing where Christine Blasey Ford will testify about an accusation that US Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her in 1982 in Washington, DC, Sept. 27, 2018.

Over the past 12 days, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh’s actions as a high school and college student have been at the center of a public conversation.

As accusations of sexual misconduct and even assault mount against him, Trump surrogates such as Kellyanne Conway dismiss his actions are merely those of a “teenager.” The adult Kavanaugh cannot be held accountable, such logic goes, because these alleged acts were only youthful indiscretions of a 17- or 18-year-old.

What exactly do we mean by teenage behavior? And who gets to be this kind of teenager? These questions are central to the conversation.

In the United States, the teen years are frequently assumed to be a time of experimentation, risk-taking and rebellion. But this notion of adolescence as a phase of irresponsible behavior is a relatively new invention.

The idea of adolescence: A history

It was only in the first decade of the 20th century that US psychologists came up with the idea of a separate life phase called adolescence and began treating these years as an extension of childhood.

The term “adolescence” — emerging from the Latin word for youth, adulescence— had circulated in English since the Middle Ages, but modern psychologists carved it out as a chronologically specific phase during which a person prepared for adulthood while legally remaining a child. And, as my research shows, US psychologists’ idea of adolescence took time to take root and traveled slowly to other parts of the world, even encountering resistance in places such as India.

Related: Things have changed since Anita Hill – sort of

In the US, compulsory schooling and age-based classrooms inaugurated in the 1870s laid the groundwork for imagining teen years as a sheltered phase. By the 1910s, educators came to a consensus that compulsory high school should extend until age 18. Before then, most men and women under that age could be, and were, expected to work, get married and even have children.

The most forceful explanation of adolescence as a distinct phase appeared in the work of G. Stanley Hall, founder of the American Journal of Psychology and the first president of the American Psychological Association. His 1904 “Adolescence” described a phase that spread out between the ages of 12 and 18, encompassing the breaking of voice and facial hair for boys and the first menstrual period and breast development for girls — and the emotional maturation following these physical developments.

While the end of childhood had been marked in many cultures with a rite of passage at puberty — such as the bar mitzvah or the quinceanera — he proposed that the emotional transition actually lasted longer and ended later.

Rebelliousness

Hall described adolescence as a period of rebelliousness and individualism. Rebelliousness, he believed, was a developmental requirement for the full flowering of self. He also expressed anxiety around how to manage boys’ sexual impulses during the teen years, devoting an entire chapter to the “dangers” of sexual development. More than any other psychologist, Hall contributed to the understanding of adolescence as a time of heightened storm and stress and emotional turbulence. His chosen constellation of features — rebelliousness, emotional turbulence, sexual recklessness — became the blueprint for analyzing and assessing the problems of young people.

But here’s the catch. Many of these early descriptions of adolescence were written for and about boys of the same social background as the author — white and middle-class. It was primarily such boys who could enjoy an extended childhood characterized by social and sexual experimentation. Lower-class boys and most black boys were expected to grow up earlier by entering the manual labor market and assuming responsibilities in their teens. A prolonged preparation for adulthood was actually available only to those with economic means.

Double standards

A similar double standard is echoed today in the way Kavanaugh’s supporters grant him leeway. Sympathetic accounts contextualize Kavanaugh’s behavior as part of boys’ culture at the elite institutions where he studied and just “rough horseplay.” This reaction is part of a social tendency to see wealthy white boys’ actions as innocently naughty, rather than dangerous. Black boys, on the other hand, routinely experience “adultification,” as historian Ann Ferguson called it — the assignment of adult motivations and ability. We do not need to look far for contemporary examples: Trayvon Martin, age 17, was stalked and killed by a vigilante neighbor who suspected he was a threat. Even 12-year-old Tamir Rice was killed because police officers thought he was a danger. And 17-year-old boys of color are regularly tried as adults and sent to prison.

What about adolescent girls?

Expectations for teenage behavior are also deeply gendered in the United States.

Innocently naughty behavior has historically been the prerogative of teenage boys rather than girls. Rebelliousness was frowned upon if girls — whether black or white — expressed it. Historian Crista DeLuzio goes so far as to depict much of the early writing on adolescence as “boyology.” Girls were simply not imagined, in psychologists’ work, to have the same entitlement to experimentation and innocent risk-taking.

This double standard continues to permeate US culture. There is a telling relevant example from the US college context: Sororities, unlike fraternities, are bound by a ban on alcohol by the National Panhellenic Conference.

Kavanaugh’s alleged actions as a teen under the influence of alcohol have not tainted his reputation as a judge for many on the political right. But Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez are pilloried by Donald Trump as unreliable because they were possibly drunk at age 15 and 18. Kavanaugh’s own views on teenage girls’ accountability are telling: In a controversial decision he offered as a federal judge, he called to delay a 17-year-old pregnant undocumented girl’s access to an abortion. Although he claimed it was because she was a minor and needed parental consent, his delay could have forced the 17-year-old into motherhood — an adult consequence.

Social expectations

Humans going through puberty certainly experience endocrine changes and neural growth. But our social expectations for behavior are what permit — and indeed elicit — specific types of acts, such as drunken unruliness. As psychologist Jeffrey Arnett notes, Hall’s ideas about adolescent storm and stress have been widely repudiated by subsequent generations of psychologists, even if some of the physiological changes he tracked are still considered accurate. And Crista de Luzio notes that in the 17th century, youth was experienced as a “relatively smooth” period in New England Puritan culture in contrast to Europe in the same era. Widespread youthful rebelliousness, she argues, corresponded more generally with social instability.

Ultimately, there is no necessary physiological reason for holding that unruly or rebellious behavior has to accompany endocrine changes in the teen years. Our uneven expectations about teenage behavior — condoning white wealthy boys’ actions but not those of girls or other boys — say more, then, about us than about teens themselves.![]()

Ashwini Tambe is editorial director, feminist studies and an associate professor in the department of women’s studies at the University of Maryland.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.