Hurricane kids: What Katrina taught us about saving Puerto Rico’s youngest storm victims

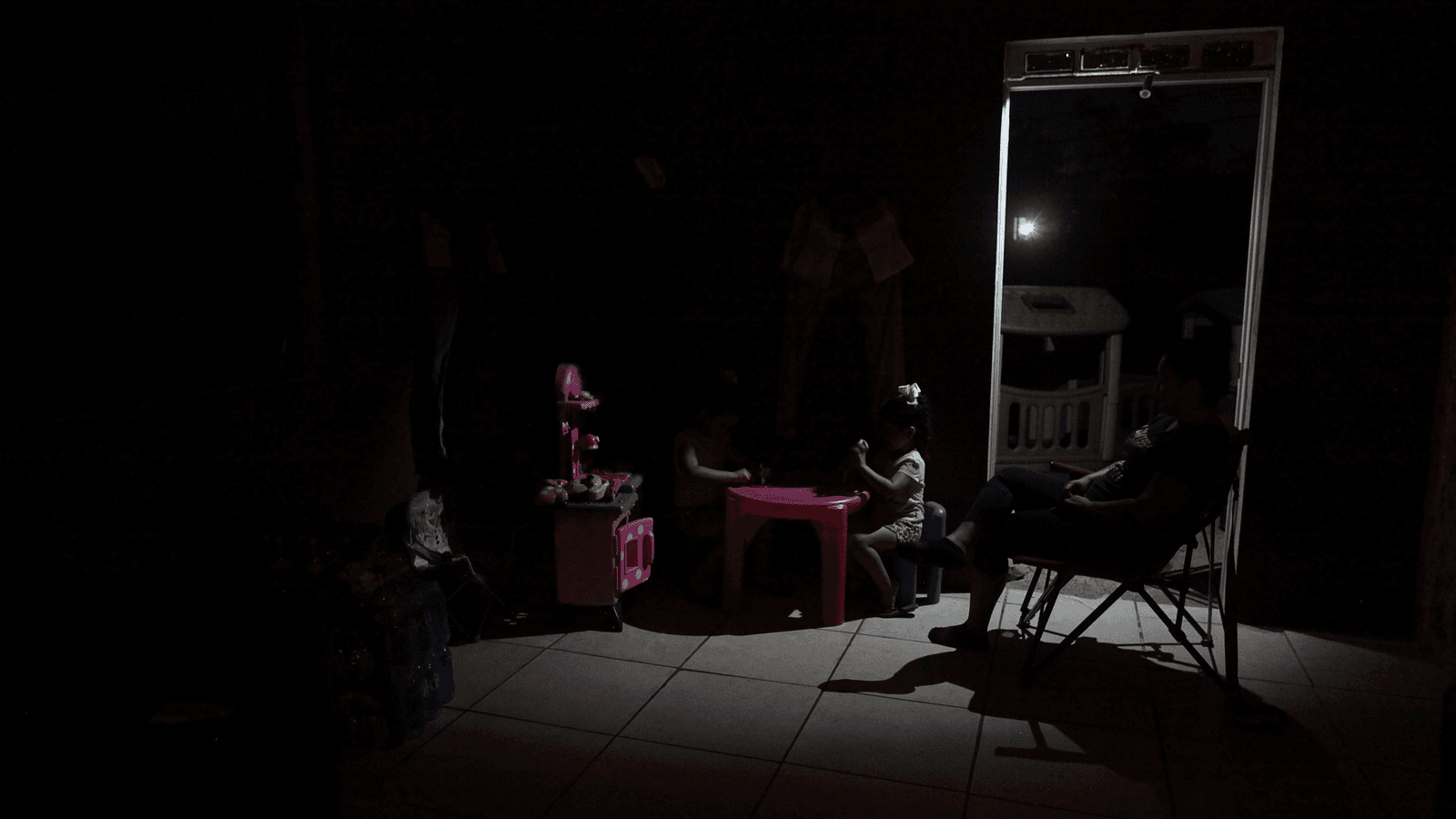

Children play next to their mother at their home after Hurricane Maria hit the island and damaged the power grid in September, in Vega Alta, Puerto Rico, Oct. 30, 2017.

The catastrophe that followed Hurricane Maria’s landfall in Puerto Rico, on Sept. 20, 2017, affected all of Puerto Rico’s 3.3 million citizens.

Everyone lost power for weeks. Half of all Puerto Ricans went without electricity until Thanksgiving. Thirty-five percent celebrated Christmas in the dark. Several thousand would not see their power restored until August 2018.

Hurricane Maria’s death toll of 2,975 ranks it among the deadliest natural disasters in United States history.

Among the survivors of the storm, one group has proved especially vulnerable: Puerto Rico’s children.

The children of disasters

An estimated 657,000 people under the age of 18 lived in Puerto Rico when Hurricane Maria hit. All experienced the intensity of the storm and its disruptive aftermath.

Research shows that children exposed to disaster may go on to suffer a host of problems, including emotional disturbance, increased stress, behavioral problems, academic troubles and greater risk of illness.

Related: Puerto Rico’s eroding beaches spell trouble for coastal dwellers

It’s been 13 years since Hurricane Katrina slammed the US Gulf Coast, killing 1,800 people and leaving behind a chaotic and dangerous disaster zone. Over a million people were forced to flee their homes. Evacuees scattered across the United States, from Dallas to New York.

We met hundreds of young Katrina victims while conducting research for the 2015 book “Children of Katrina,” co-authored with disaster researcher Lori Peek. The book followed a group of children between the ages of 3 and 18, primarily from New Orleans, for seven years.

Their stories offer critical lessons about how Maria’s youngest survivors can be better supported through the trauma of the hurricane and its aftermath.

What Katrina taught us

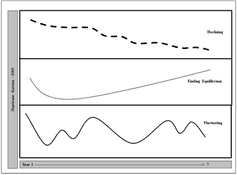

Very few children simply “bounced back” after Hurricane Katrina. After the initial period of post-storm disruption and struggle, children tended to follow one of three paths.

Some eventually found stability. They had strong family ties, reliable housing, good health, regular school attendance, supportive friendships and engaging extracurricular activities.

Other young storm victims entered what we called a “fluctuating trajectory” after Katrina. They experienced both stability and turbulence — sometimes at the same time.

For example, kids might be healthy and well housed. But, if they were living far from home — and, sometimes, from a parent — they might be distressed and getting into trouble in their new school. The ups and downs lasted for months or years.

These kids didn’t recover smoothly from Katrina. But they didn’t completely break down, either.

Some children never rebounded after the storm.

Many in this group started out in unstable settings: They came from poor, often tenuously housed families. These vulnerable children already faced difficult futures.

Katrina accelerated, intensified and solidified their challenges, triggering a downward spiral that remained serious even a decade after the storm.

After perilous evacuations from the flood zone, some children landed in unfamiliar cities. There, they struggled to make friends or even experienced hostility at schools hosting high numbers of Katrina refugees.

Other children were left homeless by Katrina. Their diets were unhealthy and unsteady. They became depressed.

Kids in this group lost years of schooling or dropped out entirely.

Schools are key to success

Disasters threaten kids’ ability to grow and thrive. They depend on adults and communities to help them survive.

Examining why Katrina’s children recovered fully, partially or not at all can inform strategies for helping young Puerto Ricans today.

School was a powerful stabilizing force in many children’s lives, our research found.

Related: A year after Maria, Puerto Rican college students find home – on the island and off

Though some New Orleans schools closed after Katrina and over 4,000 teachers were dismissed, the remaining open facilities helped students establish a regular daily routine.

School also gave them access to caring peers and helpful adults. Teachers in New Orleans counseled their students and encouraged them to get involved in extracurricular activities.

A few public schools used a curriculum designed specifically to help students process the disaster, using art, writing and therapy.

Social workers and school counselors, both in New Orleans and elsewhere, were a crucial support system for Katrina victims.

Schools also gave kids the opportunity to help other kids, which we found was an important path toward healing. This confirms studies documenting that youth experience positive mental health effects from assisting others.

Resources of survival

The centrality of school in Katrina recovery does not bode well for the children of Puerto Rico.

In the year since Maria, our research team visited dozens of communities across the island to compile data on the status of utilities, services and conditions. Our ongoing disaster research indicates that the future of Puerto Rico’s children is at stake.

This summer, after a tumultuous 2017 school year that began with Hurricane Maria, 265 of Puerto Rico’s 1,100 schools were closed due to dropping enrollment and education budget cuts.

The move destabilized the lives of thousands of children, who started the 2018 academic year in a different building with new teachers and, oftentimes, many challenges at home.

We recently experienced the closure of a school first-hand. In June we learned from concerned parents and teachers at Luis Muñoz Rivera Elementary School that the school would shutter. Parents protested outside the facility for weeks.

By late July, parents were confused because they still did not know which schools their kids would attend, how to get there or if services for special needs children would be available.

Schools in rural areas like Mayemel were the most likely to be shuttered in Puerto Rico’s downsizing. Such closures affect many of the same students who suffered most acutely from shortages of food, electricity, internet, clean water and other critical services for months after the storm.

Resources matter

Based on our research in New Orleans, this is cause for serious concern.

For some Puerto Rican children, Hurricane Maria was a prolonged crisis that exacerbated serious pre-existing problems like poverty, hunger or lack of stable housing.

According to the Census’ American Community Survey, 57 percent of Puerto Rican children live in poverty, versus just 21 percent of children on the mainland.

Now, some of these vulnerable kids have also lost their schools, which in New Orleans proved such a critical stabilizing factor.

Related: In Puerto Rico’s coffee country, ‘We have to motivate the farmers to come to the soil again’

School was not the only factor influencing children’s recovery after Katrina.

The New Orleans children most likely to land on their feet were those with employed and educated parents.

Such families were able to navigate the maze of multiple bureaucracies necessary to receive government assistance, insurance payouts, disaster aid, critical recovery information and the like. Their had strong social networks that could provide temporary housing and job opportunities.

We did identify a small group of less well-off children who survived the storm’s aftermath thanks to robust support from helpful teachers, counselors and shelter workers, well-funded schools, government relief programs and nonprofits like Habitat for Humanity.

Children in Puerto Rico are unlikely to benefit from such resources.

The island’s slow-moving financial crisis – which resulted in a May 2017 bankruptcy – had already forced the government to slash public services before Maria.

As a result, the island has ever fewer doctors, guidance counselors, sports leagues and programs like those that provided crucial recovery support to Katrina’s less well-off victims.

Who to target

We fear many Puerto Rican children will see their life chances diminished by Hurricane Maria.

Those most at risk now are the youngsters who’ve experienced cumulative struggles: kids from poor and isolated communities that received little disaster assistance after Maria and where local schools have closed.

Lessons from Katrina tell us that, to recover from this acute trauma, such children will need well-funded public services and community support, both immediately after the storm and for years to come.

But the island’s development shows mixed outcomes and the coming years present a disconcerting financial situation.

Alice Fothergill is a professor of sociology at the University of Vermont and Jenniffer Santos-Hernández is a research professor at the Centro de Investigaciones Sociales at the University of Puerto Rico — Rio Piedras.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.