American Icons: ‘Walden’

American Icons: “Walden”

“Walden” doesn’t really have a plot. It’s one part memoir, one part self-help and 10 parts rant about everything wrong with American society. So why do we still read Henry David Thoreau’s memoir about living in the woods?

Laura Dassow Walls, author of “Henry David Thoreau: A Life,” explains that Thoreau didn’t come from a rarefied literary world. He was born in 1817 to a middle-class family in Concord, Massachusetts, north of Boston. The Thoreaus ran a boarding house and a pencil-making business. Henry attended Harvard on a scholarship. After he graduated he tried teaching, freelance writing and working in the family pencil factory.

But by 1845, when he was 27 years old, he was “at a crisis,” Walls says. “He’s tried a number of pathways, none of them have satisfied him. Some of them have been pretty disastrous.”

Worst of all, his brother John had died. They had been close, and Henry took John’s death hard.

“That sense that he owed a deep debt to his brother was a big part of his life,” Walls says.

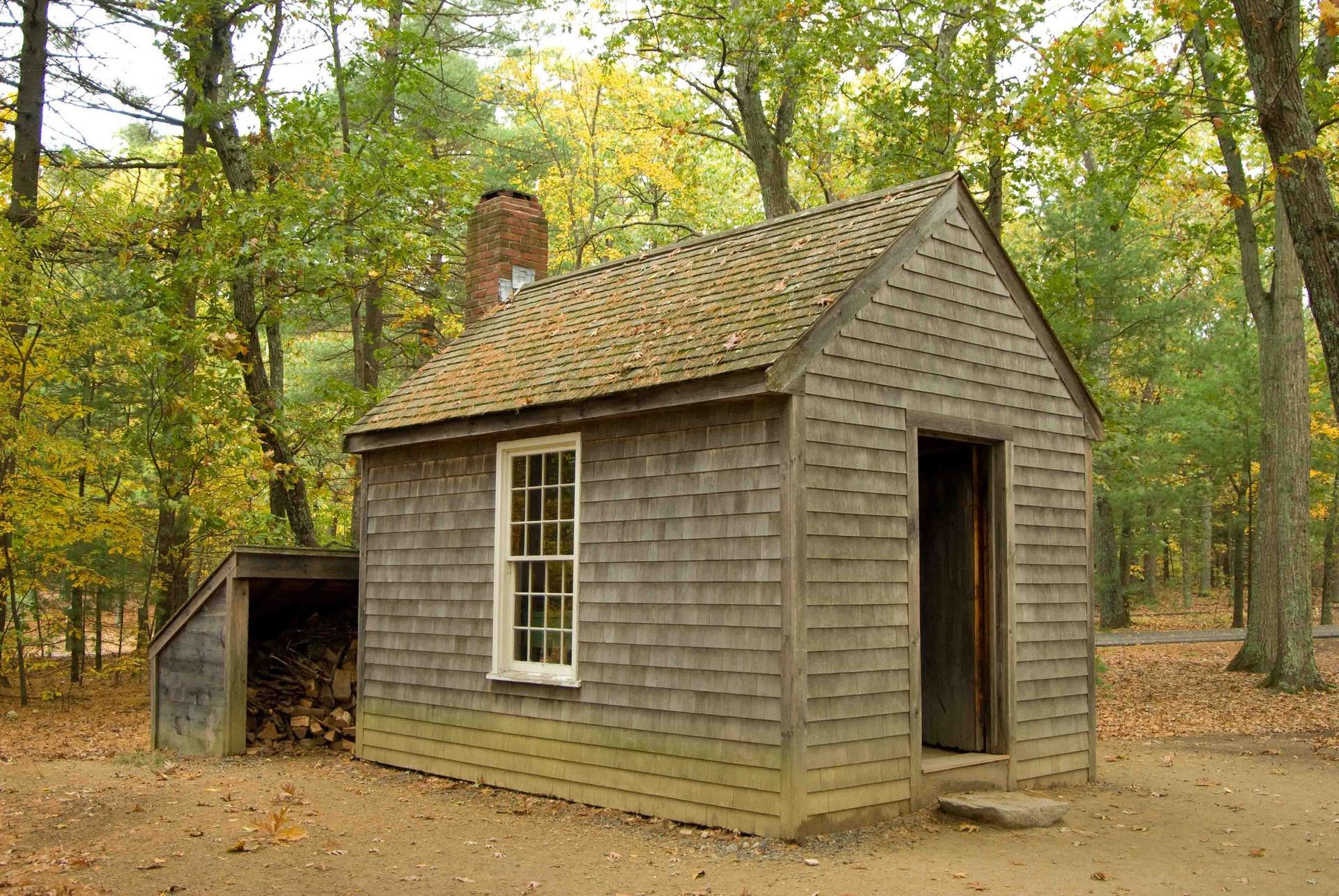

He wanted to write a book about a trip he and John took, exploring the Concord and Merrimack rivers. And he dreamed about writing it in complete isolation, in a cabin by Walden Pond, on the outskirts of Concord.

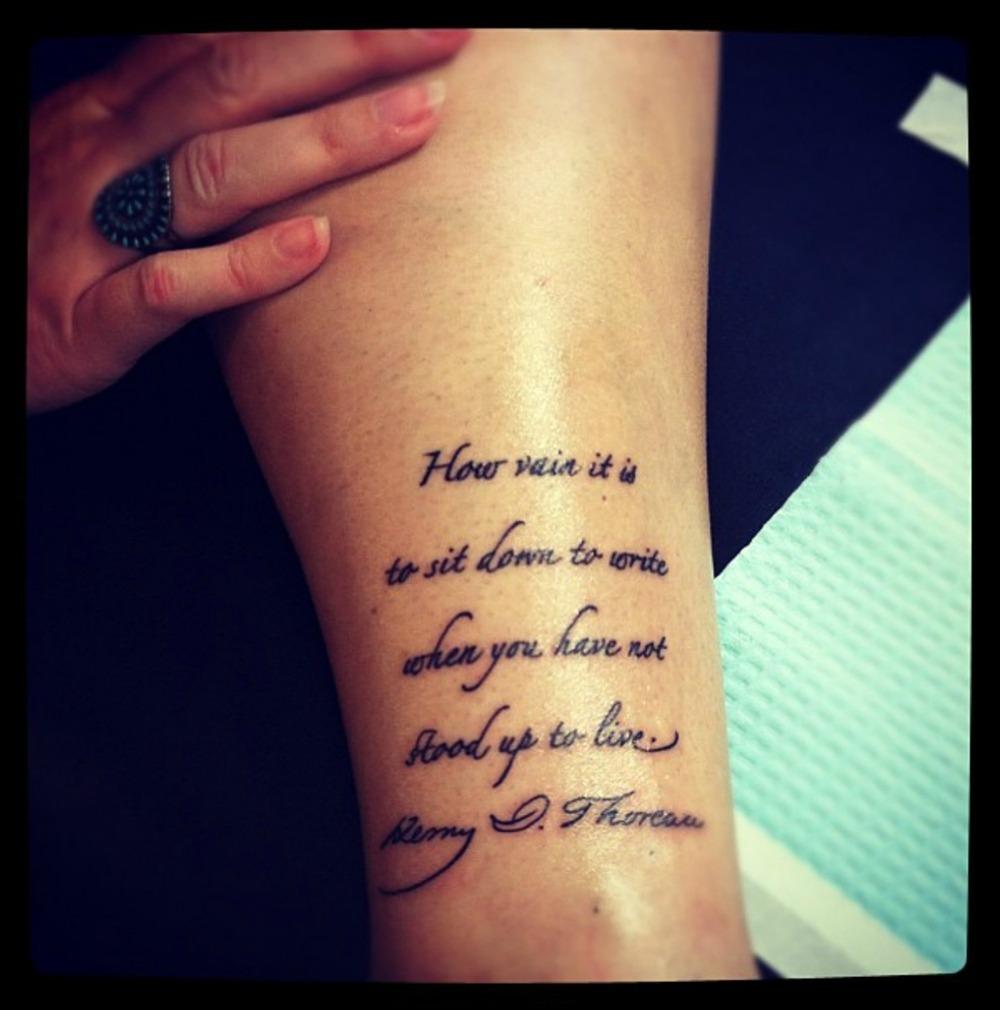

In “Walden,” he writes: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

“In many ways, we see Thoreau as the founder of environmental thinking,” Walls says.

Thoreau’s close attention to the natural world was related to his Transcendentalism, the belief in a “divine principle” in all things. “He could see it in trees, he could see it in a pond, he could see it in the animals around him.”

Thoreau lived at Walden Pond for two years, two months and two days. But he wasn’t all alone in the woods — he received frequent visits from friends and family. His cabin was visible from the road, and Walden Pond was a popular recreation spot.

“It was not secluded,” says Jeffrey S. Cramer, curator of the library of the Thoreau Institute at the Walden Woods Project. “He was not a hermit. He was not living a wilderness existence away from people.”

That fact has led some to charge Thoreau with hypocrisy. But that charge is based on a faulty reading of the book, according to Robert Sullivan, author of “The Thoreau You Don’t Know.”

“We think that he didn’t really get back to nature,” Sullivan says. “He doesn’t shy from the fact that man-made stuff is in the ‘wild.’ We keep thinking the environment is over there. But the environment is everywhere.”

American Icons is made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.