Tested but untreated: How Uganda’s new AIDS efforts are leading to a drug shortage

Patients wait to collect their HIV medication in Uganda at Mayuge Health Centre III in Uganda.

In many parts of the world, HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence.

Thanks to lifesaving drugs —and foreign financing to buy them —countries that were once the epicenters of Africa’s AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s have slashed infection rates in two and reduced deaths by nearly half.

With new efforts to eradicate the virus worldwide, and millions in US and foreign funding every year, some say the end of HIV/AIDS is near. But those same efforts are having the opposite effect in Uganda, where poor planning, lack of donor accountability and chronic budget gaps are leaving thousands of patients without treatment and US and Ugandan policymakers washing their hands of responsibility.

With the country’s HIV/AIDS rate expected to rise and clinics struggling to supply medication to a growing pool of patients, some say Uganda is jeopardizing the gains made in the last two decades and leaving the country vulnerable for a renewed epidemic in the coming years.

A dearth of lifesaving medication

Inside a dimly lit clinic in the southeastern Mayuge district, two dozen women wrapped in colorful fabric wait on wide wooden benches for their names to be called. Outside, more patients lie in a grassy field, talking quietly to one another, infants cradled in their arms.

Wabulungu Health Clinic III provides essential HIV/AIDS testing and treatment services to some of the poorest patients in the region.

But since last November it has experienced shortages — and sometimes complete stock-outs — of lifesaving HIV/AIDS medication, leaving patients waiting for weeks or months.

The stock-outs at Wabulungu are hardly unique. Shortages of HIV/AIDS drugs have been reported in at least eight districts across Uganda, some beginning more than a year ago.

According to government drug stock records, public clinics across Uganda are failing to provide lifesaving medication, despite approximately $657 million in US and international support last year and a new United Nations initiative to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030.

“See that woman?” asked Annette Babinye Ayazika, a community health worker at Wabulungu. She said the woman’s viral load — the amount of HIV virus in her blood — is seven times above what’s considered high. “They gave her an [HIV] test and no medication.”

‘Test and treat’ and ’90-90-90′

For many, Uganda is a beacon of hope in Africa’s long fight against AIDS.

An epicenter of the continent’s HIV epidemic in the early 1990s, this small landlocked country known as the “Pearl of Africa” slashed its infection rate from almost 15 percent to 6.5 percent and reduced the number of annual deaths by nearly half over the past three decades.

Its relative success is easy to understand. While some African leaders argued over the moral conundrums of treating patients with AIDS — or even the disease’s existence — Uganda’s leaders acknowledged the deadly virus early on and quickly established education and prevention campaigns to curb the disease.

Yet while the US approved the first drug to treat HIV in 1987, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that antiretroviral therapy (ART) — an umbrella term for a combination of drugs used to suppress the HIV virus and prevent it from spreading to others — became available in Uganda, but there were limitations. The high cost and high demand for the medication meant only the sickest and most vulnerable patients could access it.

That was until 2016, when Uganda adopted a set of guidelines by the World Health Organization that widened the pool of patients eligible to receive free ART in government clinics. Known as the “test and treat” policy, the guidelines expanded the criteria for ART treatment to include anyone who tested positive for the virus, regardless of the severity or progression of their disease.

Uganda’s commitment to “test and treat” was combined with another major program by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) known as the “90-90-90” targets. These three goals aimed to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030 by ensuring that 90 percent of people with HIV know their status, 90 percent of those who test positive receive ART, and 90 percent of those are no longer able to spread the disease through the use of ART by 2020.

Together, “test and treat” and “90-90-90” signify some of the most aggressive and far-reaching attempts yet to curb the virus.

“We’re back on the route to being in control of the epidemic again,” said Dr. Nelson Musoba, director general of the Uganda AIDS Commission, which operates under the Office of the President of Uganda. “We think we are on the course for achieving the overall goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.”

However, Uganda remains one of the poorest countries in the world with much of its HIV/AIDS outreach and treatment programs dependent on foreign financing.

Uganda receives about $402 million annually from the US-supported President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and another $255 million each year from the international agency The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Together, the two organizations provide close to 90 percent of the funding for ART drugs in Uganda, said Karusa Kiragu, the UNAIDS country director.

Still, implementing “test and treat” is the job of the Ugandan government.

Uganda’s health care system has long been one of the world’s most underfunded and overburdened with only one doctor for every 24,725 patients and a projected $918 million budget deficit in funding for HIV/AIDS outreach and treatment.

Despite calls by the US agency USAID to double their current domestic funding for ART — or risk the success of the ambitious program — Uganda decided to move forward with implementing “test and treat” in hopes of achieving the first “90” goal: diagnosing 90 percent of the population for HIV.

However, domestic funding remained the same.

The launch of “test and treat” meant more patients were testing positive for the virus, forcing already overburdened clinics to double their caseload in just eight months, Henry Zakumumpa, a health systems researcher at Makerere University said.

But the influx of new patients wasn’t matched with more funding and neither government nor foreign donors were prepared to cope with the financial implications of such wide-reaching and costly policies, he said.

More patients vying for fewer resources have left an already underfunded and overburdened system unable to cope, which Zakumumpa said contributed to ongoing stock-outs of ART across the country.

“We are spreading ourselves too thin,” he said. “Those who need these drugs more than others are getting the short end of the stick.”

Reports of widespread medication shortages began soon after the launch of “test and treat” with reports from the Ministry of Health citing “less than two months of stock” for most ART in Uganda in June 2017. Similar shortages of ART as well as a complete stock out of Nevirapine, a component of the ART combination, were reported in November 2017. By February 2018, the Ministry was completely stocked out of Septrin, a complementary medication that prevents infections in patients with weak immune systems. That shortage was projected to continue through August 2018, when the Global Fund is scheduled to deliver more.

But the Ministry of Health was quick to dismiss any potential issues with drug stock levels across the country.

“We have not had a situation where we have no ART,” Joshua Musinguzi, manager of the Ministry of Health’s AIDS Control Program said. “Even when we run low at a national (supply) level, we work with the partners to make sure we never get to zero [drugs].”

Zakumumpa disagrees.

“The shortages were very widespread indeed,” he said. “They are actually country-wide.”

Drug shortages handcuff clinics

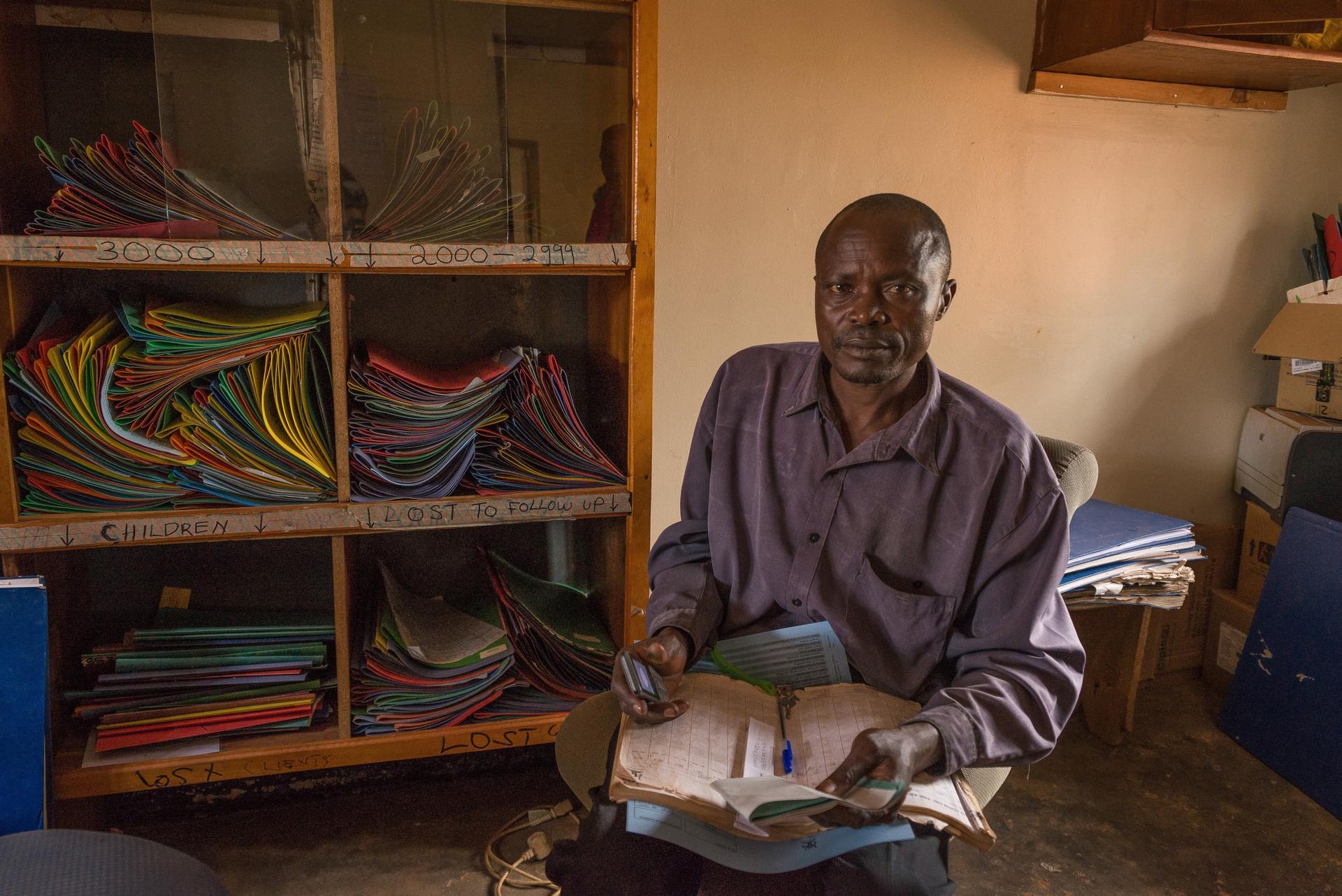

Every Friday, hundreds of patients wait under a red tin roof to collect their HIV/AIDS medication at Mayuge Health Centre III in Uganda. Many bear the signs of advanced-stage AIDS: hollow cheeks, rash-speckled legs, extremities thin and elongated from months of wasting.

Since November this clinic, like Wabulungu, has faced chronic shortages of ART, Nevirapine and Septrin.

“Many people are getting tested and coming for the drugs, but the drugs are not here,” said Paddy Babolana, an HIV coordinator at the center. “We just have too many [patients]. The drugs are consumed, and by the time [the next supply arrives], the old stock is finished. So we always experience stock-outs.”

Despite multiple emergency orders, all eight district-level ART facilities in Mayuge have been out of Septrin for months, said Babolana. His clinic is responsible for 3,775 patients; other clinics, he said, accommodate twice that number. Most are also short on second-line ART, an alternative HIV treatment used by patients who cannot tolerate the primary ART combination given to patients when they are first diagnosed.

Babolana blames the shortage of drugs on “test and treat” and “90-90-90.”

“With these resources we have now,” he said, “the ‘90-90-90’ program will be impossible.”

Babolana is not alone. Across central, eastern and western Uganda, health-care workers report similar frustrations: an uptick in patients but a continued lack of drugs.

“Before, clinics gave ART to patients with high viral counts,” said Ruth Loubega, a nurse at the Omoana House facility in southern Uganda. “But now you test positive, you immediately take the medication.”

Omoana House provides pain-management and end-of-life care to HIV-positive children. Last year, Loubega said, it was out of Septrin for two months.

“I don’t know what happened,” she said. “[There were stock-outs] all over the country.”

Zakumumpa said that between May to November 2017, health facilities in at least six districts suffered stock-outs of second-line or pediatric ART, as well as tuberculosis drugs “but the period could have been even longer.”

Monica Abaroyobera, a clinic manager at Wabulungu, could commiserate. “Last month we had no drugs,” she said. “We tell [patients] to keep on sharing with others. Or sometimes we can borrow [medication] from other facilities, if they have [it].”

Last January, Dr. Julius Bamwine, the district medical officer in Ibanda, in western Uganda said “the supply levels have worsened in the last two to three months.” All seven of the ART clinics he manages were low on a first-line medication, he said, adding that the last two supply shipments were missing second-line ART completely.

“In January, there were one or two weeks when there were no drugs at all,” said Ignutious Lusalalira, a community health worker at Mayuge Health Clinic III. “If [the government] doesn’t fix this, people’s immunity will get worse.”

“Our patients will die,” added his colleague Sarah Bwenene.

Zakumumpa said the “test and treat” policy may be partially to blame. But it’s the “entire cascade” of Uganda’s drug procurement and supply systems that is failing to provide enough medication.

The country’s supply chain is managed by the National Medical Stores (NMS), a government arm that supplies pharmaceutical drugs and medical equipment to all government facilities in the country.

Clinics like Babolana’s receive quarterly shipments from NMS. But, he said, they rarely contain enough medication. Sometimes they’re missing certain items all together. Even the Ministry of Health reported the NMS had less than three months of stock for most (ART) medicines in a June 2018 report.

Aside from funding gaps, Zakumumpa said there are several other reasons for the shortages: drugs expiring prematurely due to poor storage conditions, inaccurate drug supply forecasts, poor record keeping and crumbling infrastructure that makes drug delivery nearly impossible.

But one thing is clear, he said. “What we now know is that the shortages were associated with national-level factors … due to a centralized medicine supply system in Uganda,” he said. “Supply-chain bottlenecks.”

Government minimizes reports of stock-outs

Not everyone agrees. Ministry of Health officials minimize reports of widespread ART stock-outs and supply-chain problems.

“There may be low stocks, there may be limited quantity, but there [are] always some drugs,” said Musinguzi.

Others like Musoba of the Uganda AIDS Commission said he was aware of shortages in northern, eastern and central Uganda last October but calls them growing pains caused by “test and treat”.

“[Stock-outs] may be a result of the transition of the implementation [of test and treat],” he said. “But there has been a response by National Medical Stores to address the gaps.”

However, the Ministry of Health cited shortages and complete stockouts of Septrin across Uganda that are expected to continue through October 2018 when the Global Fund delivers more according to a June 2018 report.

The US State Department, which speaks for PEPFAR, maintained that Uganda “is nearing epidemic control” by diagnosing more people with HIV but acknowledges the country “has faced challenges to ensure public-sector clinics have sufficient stock of ARVs.”

They also underscored the need for more domestic funding.

“Achieving epidemic control … will require the Government of Uganda to significantly increase its investment in the health sector to ensure that ARVs and other health commodities are available for all Ugandans who need them,” the State Department said in a statement.

In April, the US government announced that it would increase its budget for HIV prevention and treatment in Uganda from $402 million per year to $408 million, in order to cover programs from October 2018 to September 2019. USAID also provided $18.7 million worth of ART to Uganda to “fill gaps in the public sector” late last year. Domestic funding for ART has remained the same said Kiragu.

Still, reports of ART stock-outs continued through May 2018 and “are still ongoing as we speak,” said Zakumumpa.

‘Successes and reversals’

Until the ongoing shortages across Uganda are solved, health-care workers like Babolana said they will be forced to ration their ART medication for those most in need, redistribute excess drugs from nearby health facilities, or ask patients to share their drugs. In some cases, they’ll have to turn patients away completely.

Standing near a growing line of patients pooled under the clinic’s red tin roof Babolana asked the crowd a question.

“Who took Septrin last night?” he said. Some raise their hands. Most do not.

Babolana said he’ll continue encouraging his patients to buy Septrin on their own, even though nearly a quarter of the district lives on less than $1 a day. Others, he said, are lucky enough to enroll in hospice care due to the shortage.

“When they go in hospice, they at least get some Septrin,” he said.

Nearly 70 miles away from Babolana’s clinic, Musoba of the Uganda AIDS Commission reviews a dozen photos depicting the impact of ART shortages across the country.

There’s a photograph of Loubega from Omoana House paging through records of children who died from HIV/AIDS under her care, another of Rukia Webombesa speaking to hospice nurses just a few days before dying of HIV/AIDS, a third showing long lines of patients waiting to collect ART and Septrin in Mayuege only to discover the clinic’s shelves have been empty for weeks. All were taken between September and October 2017.

“I’m surprised,” Musoba said as the last image flashes across the computer screen. “Many questions are going on in my mind about why this is happening.”

Musoba said he hasn’t received any complaints about ART shortages from clinics in southeastern Uganda.

“I am not disputing your earlier story,” he said while examining a photograph of a dozen women waiting for ART at Wabulungu Health Clinic III. “But If I go to a clinic and the outpatient (room) is full and people are waiting … it means a service is being provided,” even if that service is just an HIV test.

Getting a test, Musoba said, is better than getting nothing.

Musoba does admit some clinics could be experiencing ART shortages, but maintains those are limited and temporary. Insinuating the shortages are chronic and countrywide is not only an incorrect accusation, it’s a condemnation on the government and agencies that are trying to help, he said.

“Uganda has had both successes in the past, and some reversals,” Musoba said. “But if what you’re raising is happening at the magnitude that you’re portraying … it’s an indictment on very many groups that are supposed to be supporting this response.”