Why this Hiroshima survivor dedicated his life to searching for the families of 12 American POWs

President Barack Obama hugs atomic bomb survivor Shigeaki Mori as he visits Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, Japan, on May 27, 2016.

You’ve probably seen Shigeaki Mori. A photo of him hugging President Barack Obama was published around the world after Obama visited Hiroshima in 2016.

Mori, now 81, is a Hiroshima survivor.

In a 2016 speech at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Obama said atomic bomb survivors have stories that make war less likely and cruelty less easily accepted. He mentioned Mori that day, highlighting him as “the man who sought out families of Americans killed here because he believed their loss was equal to his own.”

Mori has spent much of his life trying to get recognition for 12 American airmen who died alongside tens of thousands of Japanese after the atomic bomb was dropped 73 years ago.

‘I couldn’t even see my fingers’

Shigeaki Mori was 8 years old when the bomb destroyed Hiroshima. Mori was on his way to school — he didn’t have summer vacation — when the bomb was dropped about a mile and a half from where he was walking across a bridge. He was blown into the river.

“I couldn’t even see my fingers enough to count them because it was so dark inside the mushroom cloud,” Mori says.

Mori doesn’t know how much time passed. Maybe 30 minutes, maybe an hour, but eventually, he could see well enough to climb out of the river. As he fled, there were people collapsed everywhere in the streets. He was crying.

“I was so frantic in trying to escape that I just made my way, stepping on the faces and heads of these people,” he remembers.

Then Mori says, it became very cold. The sun was shut out and there was a fierce shower of black rain.

“The black rain hit my body. It was very painful,” he says.

Mori says his shirt became black and hurt his skin, so he took it off. He was cold, so he wrapped himself in a newspaper he found at a makeshift shelter.

Hiroshima was on fire. All the houses were aflame. Mori remembers it being so bright at night that he could read the newspaper rolled around his body.

“After three days, I thought I was going to go crazy. Thinking back now, maybe because I had not had a drop of water,” he recalls.

So he left the shelter in search of food. He had heard a rumor that he could get rice balls at his school, but when he got there, all he found was more death.

“What I saw was a mountain of dead bodies,” he says.

‘I didn’t think the numbers made sense’

Mori and his family stayed in Hiroshima after the bombing. He eventually raised his own family there.

After the war, Mori says people were afraid to talk about what happened that day, but sometimes in the news numbers would be quoted from the City of Hiroshima’s official documents. Mori knew those numbers were wrong. It was recorded that there were 800 dead at the school where Mori had fled to that day. But he had witnessed many more bodies than that.

“The original reason for my starting this is because the number just didn’t match. I didn’t think the numbers made sense,” he says.

Mori has a knack for minute details and he’s a history buff, so in his late 30s, he decided he would finally correct the record of how many people actually died in Hiroshima.

He began searching public records and interviewing people about what happened on Aug. 6, 1945. When he found errors in the records, he’d bring them to city officials, and they encouraged him to continue his research.

‘There were 12 Americans in the jail’

It was while interviewing fellow survivors that Mori learned about the existence of 12 American POWs. They had been on a mission to bomb Japanese ships when their planes were shot down and they were taken prisoner in Hiroshima.

When Mori learned of their stories, he realized that regardless of what side of the war you are on, everyone experiences loss the same way. That’s why he wanted to share the story of the American airmen who died in Hiroshima because no one really knew about them.

“I was sure the bereaved families all want to know the true story, so I wanted to let them know … because they are human beings,” he says.

Mori searched for POW families for years, trying to add their names to Memorial Peace Park in Hiroshima, which lists the names those who died. Names can only be added with the permission of family members.

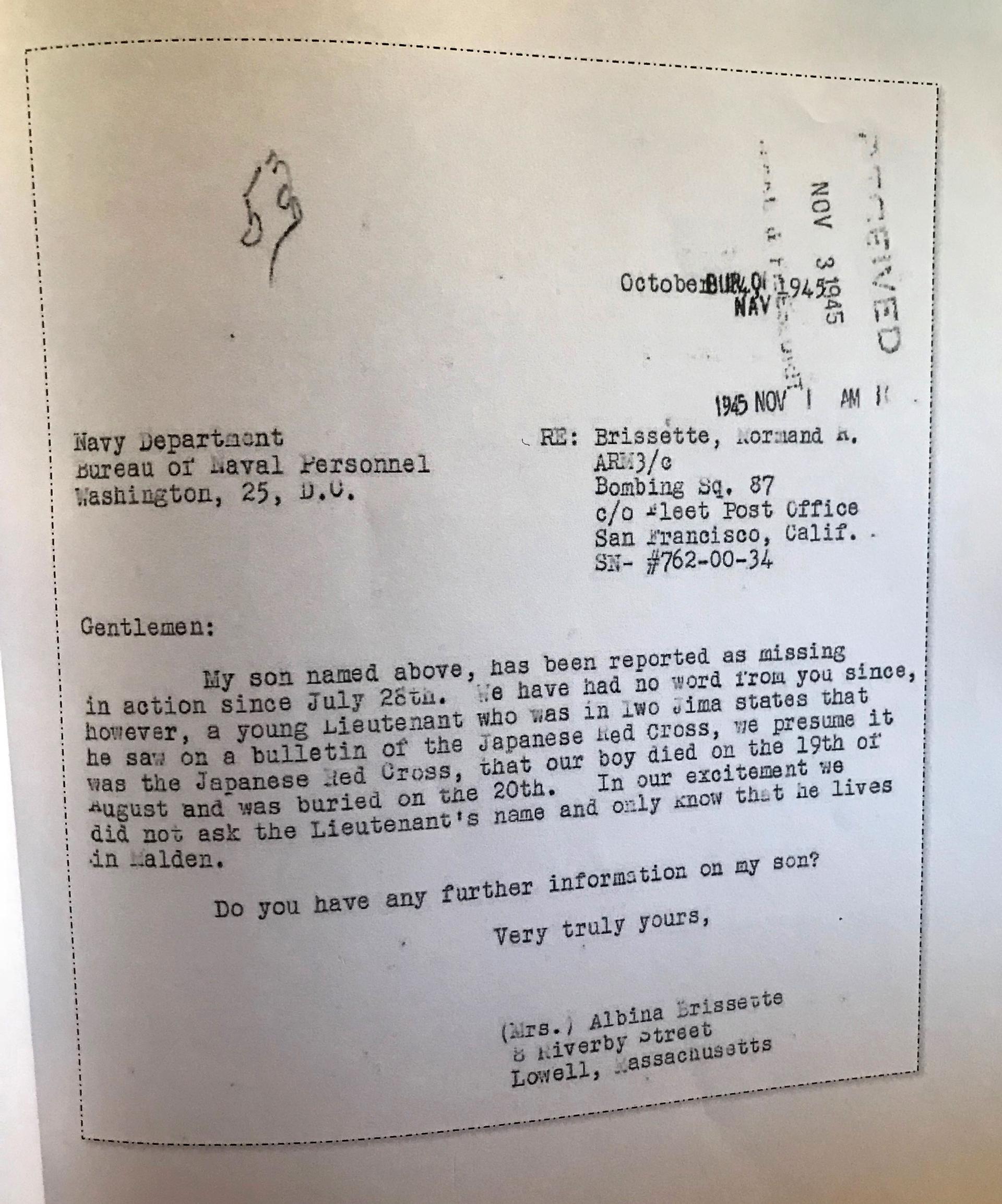

One of the family members who Mori connected with is Susan Brissette Archinski. She’s the niece of Normand Brissette, a Navy gunner who was taken prisoner by the Japanese during WWII and who died in Hiroshima.

Archinski, 58, lives near Lowell, Massachusetts, not far from where her uncle grew up.

Mori first made contact with Archinski’s aunt and Normand’s sister, Connie Brissette-Provencher, in 2002, when he was trying to get permission to add Normand’s name to a memorial in Hiroshima.

Mori wrote letters to Brissette-Provencher in Japanese, and a nun at the local school would translate them. Archinski says that, growing up, her father didn’t talk much about his brother’s death, so the family only knew a few basic details. Later on, Archinski’s husband requested Normand’s military records. Those records, along with the information Mori provided, helped the family develop a clear picture of what happened.

“When the Americans dropped the atomic bomb there were 12 Americans in the jail,” Archinski says. “I’m not actually sure that America knew that they were in that jail, because there were no prison camps there.”

When America dropped the bomb on Aug. 6, 1945, nine of the American prisoners died immediately. Normand Brissette and one of the other prisoners had been a few blocks away on latrine duty. They jumped into a cesspool and that saved their lives, at least for a while. The timeline is fuzzy, but they ended up on a truck driven by a Japanese man called Tank. Tank took the men to a doctor.

But Normand Brissette met other Americans on that truck, including a lieutenant from Massachusetts.

“I guess they spoke and I guess when Normand realized he was from Malden, [Massachusetts], he asked him to go see my grandmother when he came back to the states, and he did,” Archinski says. “So my grandmother was all excited she thought well, ‘When is he coming home?’ And he said, ‘I thought you knew that he’s not coming home.’”

Normand died from radiation sickness 13 days after the bomb was dropped. He was 19. Archinski’s grandmother wrote to the Navy and relayed what she had learned from the lieutenant who had seen her son. It wasn’t until a year later that she received official confirmation of the lieutenant’s account.

Years later, Archinski’s husband bound those letters and Normand’s military records into a book and sent them to Mori. Then, in 2015, Archinski was invited to meet Mori in person as part of a documentary film about the American POWs and Mori’s efforts.

“I think I was actually the first family member that actually went to Japan to meet him,” she says.

Their meeting was big news in Japan. When she arrived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Archinski says she was flocked by Japanese reporters.

“I felt like I was a Kennedy or something,” she says. “It was like paparazzi, so it was kind of like oh my god, and it was like that the whole week. They were around me the whole week.

Mori took her on a tour through Hiroshima so she could walk in her uncle’s footsteps. They visited the hospital where he was treated, the place where he was buried before his ashes were repatriated to the United States and the military police headquarters where the POWs were jailed. On that building, there is a plaque commemorating the American victims of the bomb. It reads: “May this humble memorial be a perpetual reminder of the savagery of war.” Mori is responsible for the plaque.

“He took a second job to pay for the memorial he put in Japan for the Americans,” Archinski says. “It’s hard to understand how he could be so loving and peaceful and spend his whole life dedicated to 12 Americans.”

Earlier this year, Mori met Archinski again in Lowell, Massachusetts. He and his wife sang the Japanese national anthem at the unveiling of a new monument dedicated to the American airmen who died in Hiroshima.

Two days before Mori arrived in Lowell, Normand’s sister, Brissette-Provencher, died. Mori, who had been looking forward to meeting her, did not get the chance.

Mori was in the United States to promote “Paper Lanterns,” a documentary film about his life’s work, which will be released Aug. 7, 2018, on video-on-demand platforms.

Mori never received any financial assistance in the 42 years he worked to correct history, but he got to meet the families of the POWs he spent his life researching, and he got to meet the president of the United States.

“I was emotionally overwhelmed and could not stop the tears from continuing to flow,” Mori says. “Seeing me crying, President Obama reached out his hands to me and pulled me up to him. … The president said nothing. I did not say a word. But our hearts were connected.”

“Paper Lanterns Trailer” from barry frechette on Vimeo.