Ahead of elections, Cambodia’s democracy crumbles

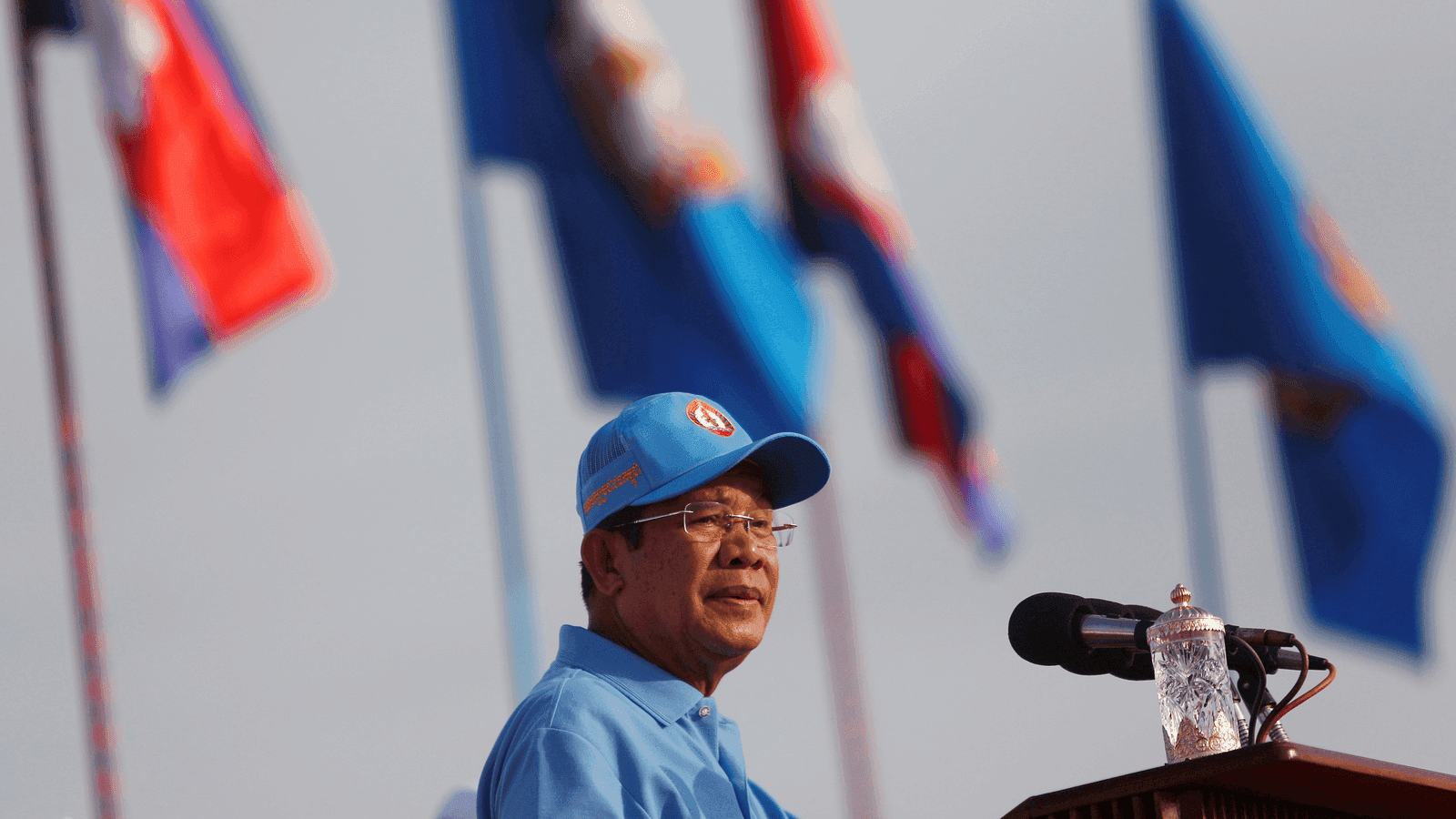

President of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen attends a campaign rally on final day in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, July 27, 2018.

Phnom Penh doesn’t sleep. In Cambodia’s vibrant capital, throngs of tourists wander through the Royal Palace and along the riverfront, expats gather at one of many organic eateries, pedestrians weave through a sea of motorbikes and tuk-tuks, and schoolkids hang out at the hulking Aeon Mall. But at least in one respect, the city is quiet these days. There are no political rallies — unless they are for Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Wednesday marked the latest show of force by Hun Sen’s government when more than 4,000 police officers dressed in riot gear and carrying automatic weapons filled Olympic Stadium in Phnom Penh. The display was intended to dissuade any protests and quell growing calls from the opposition to boycott the election.

On Sunday, the Cambodian people will head to the polls. There are a dizzying number of parties to choose from; one report counted 20 so far — all part of a façade of a free and fair election. Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has been in power for more than 30 years, has systematically dismantled the free press, dissolved the only real opposition party, restricted or outlawed freedom of expression — sometimes by force — in what has been described as the death knell for democracy in Cambodia. Hun Sen will almost certainly win reelection by a landslide.

In late 2017 The Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) president, Kem Sokha, was arbitrarily jailed by Prime Minister Hun Sen. Former CNRP president Sam Rainsy fled to France and remains in self-exile; if he returns, he will be arrested.

The arrest of the main opposition party’s leader was stunning; then, within 48 hours the second-longest-running English-language paper, The Cambodia Daily, was shut down by the government.

“That’s when we started to see the writing on the wall,” said former Phnom Penh Post reporter Erin Handley. “Even though the Cambodia Daily was technically a competitor, we would pick it up and see if they scooped us on something or what stories they put out.”

Dismantling the press

Formed in the first years after the devastation of the Khmer Rouge, the Cambodia Daily was dedicated to reporting “without fear or favor.” But in late 2017, the Daily received an exorbitant and, most agree, punitive tax bill from the government. Hun Sen had forced the Daily out of business. It’s last headline “Descent into Outright Dictatorship.”

Within a year, Handley’s paper was bought out by a Malaysian businessman with deep ties to Hun Sen and his government. The executive editor was fired and an exodus of international staff journalists followed. The Phnom Penh Post was effectively silenced.

“The media climate in Cambodia, which used to be among the freest in Southeast Asia, has changed dramatically since August 2017,” says Astrid Norén-Nilsson, an associate senior lecturer at the Center for East and South-East Asian Studies at Lund University in Sweden.

Hun Sen’s targeting of the free press — radio, print and online — is concerning to Norén-Nilsson. “The situation for journalists is now very volatile.”

More than 30 radio stations have been shut down and many international non-governmental organizations designed to promote democracy and press freedom have been ejected from the country — in some cases without notice — by the government. At least three journalists have been jailed so far. But shuttering the two news outlets critical of the regime was the end, rather than the beginning, of Hun Sen’s efforts to cement his regime.

One pivotal moment came in 2013 when the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) stunned the CPP by winning 55 seats in the national assembly. The CPP retained 68 seats but lost its two-thirds majority. The CNRP’s popularity posed a threat to Sen’s rule.

Shifting away from the West

The 2013 elections coincided with a shift in the relative importance of Western donors versus China, says Norén-Nilsson. She points to 2010 when China became Cambodia’s top foreign aid donor and largest foreign investor since 2013.

“This shift was timely in giving the Cambodian government the scope to steer away from Western development partners and follow a new authoritarian line domestically,” says Nielsen-Noren.

Cambodia’s allegiance to China is money well spent. China relies on Cambodia to be an ally within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc regarding issues related to the South China Sea.

“Certainly it is Chinese political and economic support that has enabled the government’s authoritarian turn,” Norén-Nilsson said.

Following the CNRP’s dissolution in November 2017, the Chinese foreign ministry reportedly stated that “China supports the Cambodian side’s efforts to protect political stability and achieve economic development.”

“This represents a shift from a discourse of non-interference in Cambodian domestic affairs to active support for the dissolution of the political opposition,” said Norén Nilsson.

China making a public statement is significant. Because unlike providing aid and investing in Cambodia, China publicly supporting de-facto dictator Hun Sen signal’s China’s active encouragement and desire for autocratic rule in Cambodia.

‘The Dirty Dozen’

Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a report called “The Dirty Dozen” that details the brutal loyalists with which Hun Sen has surrounded himself. Some, including Hun Sen, served under the Khmer Rouge regime. And HRW has previously accused all of them of resorting to violence. In 1997, a political party opposition rally was rocked by a deadly grenade attack that left 16 dead and injured 100 more, including one American. A few months later, Hun Sen staged a coup to oust his co-leader within the government.

A 2018 report from Human Rights Watch listed off just a few of Hun Sen’s abuses:

In his time of power, hundreds of opposition figures, journalists, trade union leaders and others have been killed in politically motivated attacks. Although in many cases those responsible for the killings are known, in not one case has there been a credible investigation and prosecution, let alone a conviction.

One particularly brazen killing took place on July 7, 2016. Kem Ley, a popular political analyst, was assassinated at a gas station. Just days before he had publicly criticized Hun Sen’s government. An arrest was made and officials tried to frame Ley’s death as a robbery gone wrong. However, many believe that the government ordered his killing.

The EU and the US have been pushing back against Hun Sen over the last year. In June, the US government invoked the Magnisky Act against Hun Sen’s bodyguard, General Hing Bun Hieng, head of the Prime Minister Bodyguard Unit (PMBU). The Magnisky Act allows the US to freeze assets of foreign actors found to violate human rights. Sen’s bodyguard has a long history of abuses and was behind recent attacks on civilians. The US House of Representatives added Hun Sen, his family and many of the “dirty dozen” to the sanctions list just this week. General Hun Manet, Hun Sen’s West Point-educated son, was appointed to head the armed services by his father earlier this year, suggesting Hun Sen is crafting a familial dictatorship.

Kem Sokha’s daughter, Monovithya Kem, an outspoken activist and CNRP deputy director for foreign affairs, was in Washington, DC, last week meeting with US officials.

On Thursday, she welcomed the sanctions: “I have been urging for such bill since January and very pleased to see it passes now,” she said in brief remarks made via a messaging app.

“Hun Sen will likely try to find creative ways to evade sanctions and maintain the charade of multi-party democracy,” she said. “I hope observers won’t let him fool them again [sic] it is time to hold Hun Sen responsible for destruction to Cambodian democracy.”

Further erosion of democratic norms includes the Cambodian government enacting a series of laws and policies directed at restricting the press and freedom of expression.

Recently, The National Election Commission of Cambodia (NEC) released guidelines for reporters covering the elections. The NEC states that journalists shouldn’t have “their own ideas to make conclusions” while reporting on the election, so as not to sow “confusion and loss of confidence” of the vote. Confusion and loss of confidence aren’t defined in the NEC guidelines leaving room for broad interpretation leaving reporters to guess what they can print without being fined or arrested.

Similarly, the intentionally vague lèse-majesté law (literally, “insulting a monarch”) was enacted earlier this year. It effectively outlaws any speech that impacts either “directly” or “indirectly affects the interest of Cambodia.”

Kheang Navy, a 50-year-old teacher, was the first person to be arrested under the new law this May. He allegedly wrote a post on Facebook that claimed the government and the monarch conspired to dismantle the main opposition party. Notably, the law also allows Hun Sen’s government to levy charges against media outlets and institutions.

Though at a seemingly dark turning point, there is optimism in Cambodia. In a country where most of the population was born after the Khmer Rouge genocide, the new generation has grown up only knowing freedoms whether through the ballot box or via ubiquitous internet-enabled smartphones.

Monovithya Kem is part of that generation. And though she feels unable to return to Cambodia over fear of arrest or worse, she isn’t giving up.

“We are not recognizing the election and calling for new election,” she said. “The fight is far from over.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!