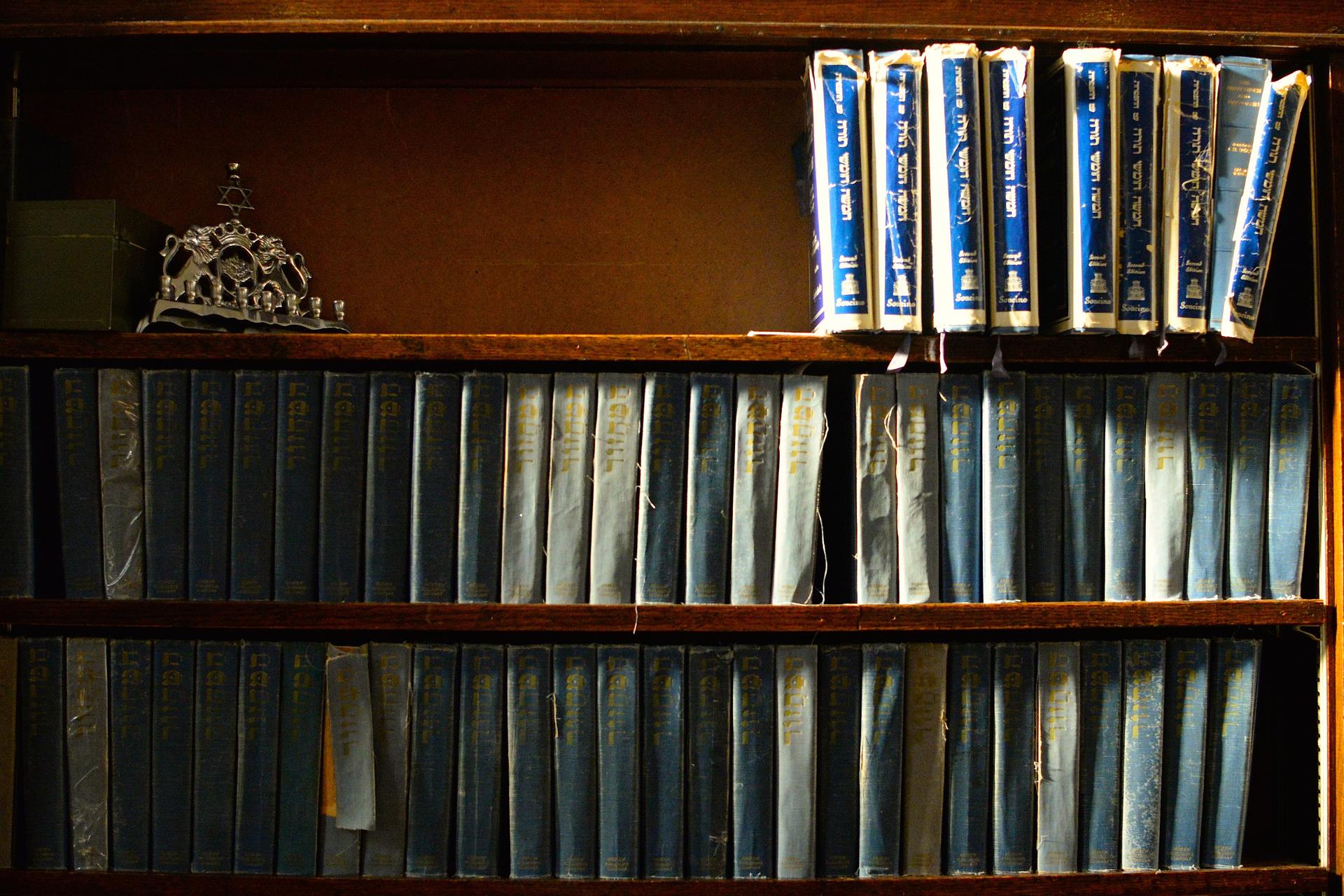

Harvey Disenhouse, one of the last members of B’nai Jacob in Ottumwa, Iowa, prays alone in the synagogue in 2016.

When Esther Hugenholtz stepped forward to give the final sermon at the B’nai Jacob synagogue in Ottumwa, Iowa, in May, she felt a rush of bittersweet emotions.

“It runs against every fiber of my being to sunset a synagogue,” says Hugenholtz, a 40-year-old rabbi in Iowa City. “I felt incredibly honored as a young rabbi to sit by the bedside of this community and pour my love into them, and bless them with this final blessing.”

There’s a story in the Torah, Hugenholtz says, when the patriarch Jacob is on his deathbed. He gathers his children around him and blesses each of them. Before he dies, he helps them to articulate a vision for their lives.

“It kind of felt like that a little bit,” Hugenholtz says. “It was a very sacred and intentional moment to say to a community, ‘You’ve run a good race. You’ve sanctified God’s name in Ottumwa for 100 years, and we will take up that baton and we will continue to run that race.’”

After more than a century as the living cornerstone of the Jewish community in Ottumwa, a town of 25,000 people in southeastern Iowa, B’nai Jacob, founded by 19th and 20th century Jewish immigrants from Russia, has joined the list of other small-town Jewish communities in Iowa to fade away. It was, perhaps, the last congregation of its kind in the state.

But even though B’nai Jacob in Ottumwa has sunsetted, a new chapter has opened on the other side of the world, in Paraguay.

There are around 700 Jews living in Paraguay — up to 1,000 by some accounts — and Pedro Federer is among them. Federer says the community’s roots date back to the early 20th century. He belongs to a small group that split away from the main congregation in Asunción, Paraguay’s capital city, earlier this year. He was looking for a more egalitarian, family-friendly worship experience. Since January, they’ve rented a house in the country’s capital to worship, and have already found someone to lead services.

They just needed a Torah.

“The population [of Paraguay] is a little over 8 million,” Federer says. “So you can see how small we are. But we still have our roots, and we want to keep them alive. The flame of light of the Torah give us this.”

The Torah is a sacred text in Judaism, sometimes called the Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. What happened next was a serendipitous — divine, even — series of connections that gave birth to an international, interfaith effort to get one of B’nai Jacob’s priceless Torah scrolls from Ottumwa to Paraguay’s capital city.

By happenstance, Oklahoma rabbi Juan Mejía was in Iowa City a few weeks after Hugenholtz gave the final sermon at B’nai Jacob in Ottumwa. He and Hugenholtz are friends and colleagues, and agreed that one of B’nai Jacob’s Torahs should be given to a small community in Latin America — Torah scrolls are valuable and difficult for small communities to acquire. Mejía works with small Jewish communities in Central and South America, including Ecuador, Mexico and Colombia.

Less than a week later, he was in his hometown of Barranquilla, Colombia, visiting a Jewish community he serves remotely. On June 8, at a wedding, he met another guest from Paraguay — part of Federer’s community — who mentioned to him that they were looking for a Torah.

Mejía reached out to Hugenholtz, who discussed it with B’nai Jacob’s few remaining members. It was a match: Of the Ottumwa congregation’s four priceless Torah scrolls, one would be sent to this small community in Paraguay.

“I find it very beautiful that there’s a lifeline of connectedness between these communities and vintage congregations in the American Midwest,” Mejía said. “It gets me misty-eyed. These communities will struggle the same way Ottumwa struggled. They will have the same blessings. That’s the beauty of small-town Judaism.”

“I come from Holland,” Hugenholtz says. “I come from a community that’s been decimated by the Nazis, and I come from a community where it’s the new normal to have small communities that struggle. I very much identify with that mission.”

There was, however, one major logistical challenge: How do you get a Torah from Ottumwa to Asunción, more than 5,000 miles away?

Enter Erin Jones-Avni and Leah Jones (who are unrelated to each other) of Kansas City and Chicago, respectively. They’re old friends.

Jones-Avni happened to be living in Paraguay with her family before she returned to the United States in July. She was affiliated with the group slated to receive B’nai Jacob’s Torah. Her parents were coming to visit her in Asunción, and offered to bring the Torah with them — if it could get to Kansas City first. She called Jones.

“Erin just knows that I’m well connected in the Jewish world,” Jones says.

Within an hour, Jones had found someone to drive the Torah from Iowa to Kansas City, a friend’s cousin who was planning a visit anyway. The four-foot-tall Torah, packed in a hardback golf club case, ended up in Amy Ravis Furey’s dining room. Jones-Avni’s brother-in-law drove to Kansas City to pick it up, and delivered it to her parents two hours away in Manhattan, Kansas.

Jones and Ravis Furey are quick to point out that most of the people who helped move the Torah aren’t even Jewish.

“So many Christian people helped,” Ravis Furey says. “At a time where the whole world seems anti-Semitic, I’ve been feeling very hopeful. It’s just been such a dark time, this has been a really happy spot.”

“I’ve been very touched by the number of non-Jewish people who have realized how important this is, and have wanted to be a part of it” Jones says. “There’s something nice when interfaith works.”

A month after B’nai Jacob’s last service, the Torah arrived in Asunción.

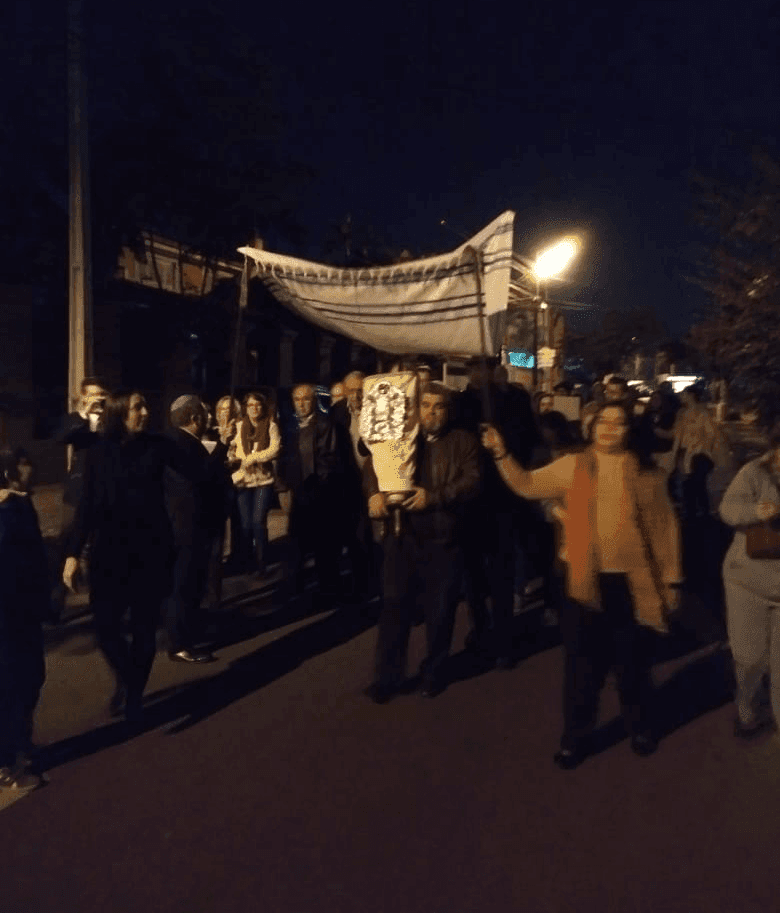

“I would say about 75 [of us] went that same day to see the Torah and touch it,” says Federer, who coincidentally was an exchange student in Iowa in 1960. The group held their first service with the Torah on July 7. In addition to Hebrew and traditional imagery embroidered on the scroll’s black shroud are the words, “Donated by B’nai Jacob Congregation, Ottumwa, Iowa.”

The community celebrated its first bat mitzvah with the Torah in July.

One of B’nai Jacob’s other scrolls will remain in Iowa City. Another will be sent to Israel. The fourth awaits a decision.

“There has always been a wax and wain and shift in Jewish demographics,” Hugenholtz says. “That’s the tragedy of the Jewish story, but that’s the triumph of the Jewish story. We have a fighting spirit in us, and we have a lot to give, and just because one community sunsets doesn’t mean another community doesn’t rise somewhere else.”

“We didn’t want [the Torah] to go to some congregation that already has six Torahs,” says Sue Weinberg, whose mother Irene Weinberg was the among last Ottumwa-born members of B’nai Jacob living in the town before she passed away last year at the age of 97. “We wanted it to go to a congregation that needed a Torah.”

“The Torah is our light. And for different reasons, the Jewish population in Ottumwa did diminish,” Federer says. “Now it will give life in another place of the world: here in the heart of South America. So the purposes for what the Torah was written, are still in tact.”

Before the Torah arrived, the community in Asunción voted to name their blossoming congregation. The result was nearly unanimous.

The spelling is a bit different, but the name is the same. They’ll call themselves B’nei Iacob.

Next: A fading Missouri monastery finds new life — in Vietnam