There’s a fight going on in schools over when history begins

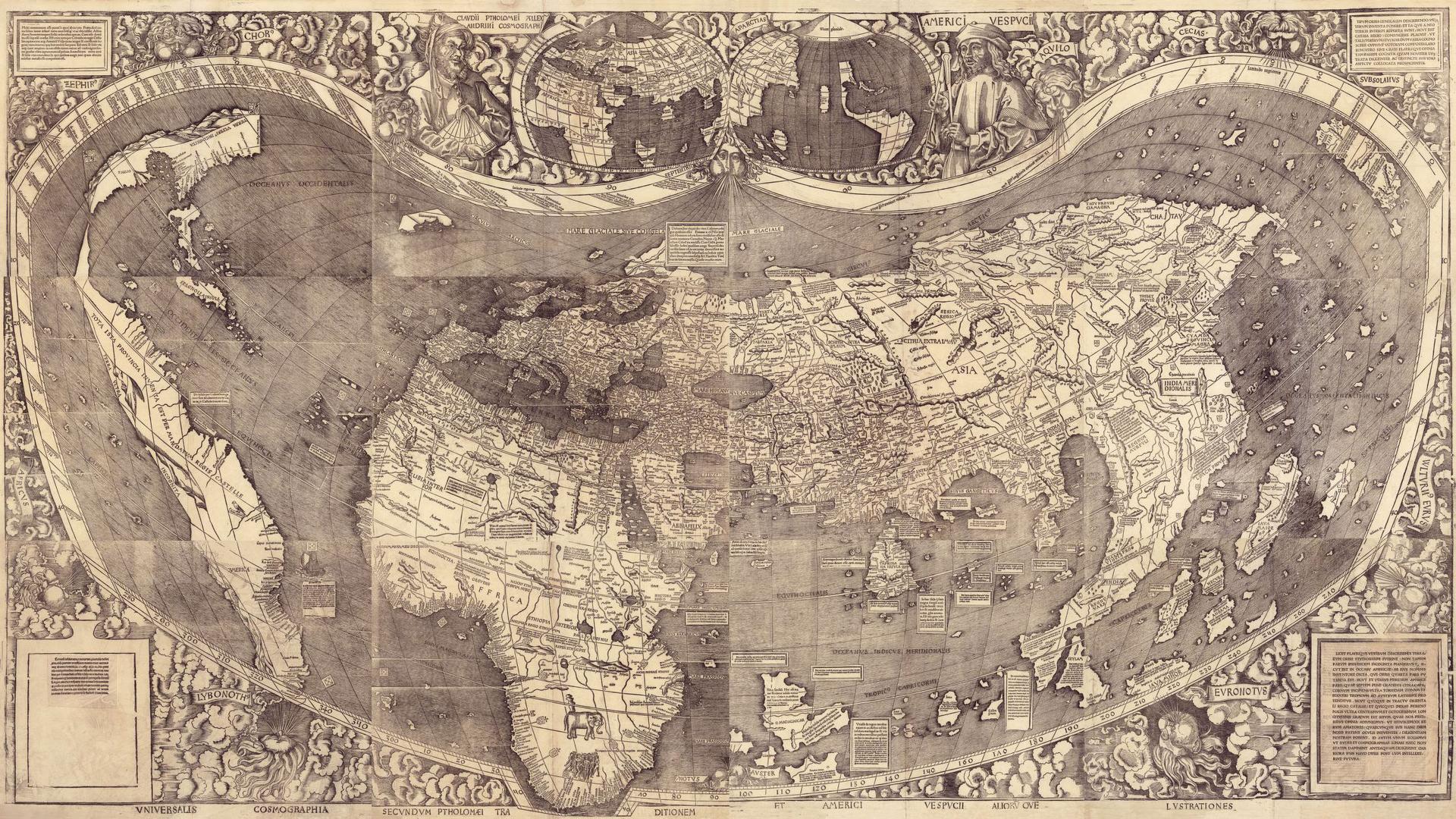

This 16th century map was the first to name America. Students and teachers fought a recent decision by The College Board to begin teaching Advanced Placement world history courses at 1450.

AP world history covered about 10,000 years when 16-year-old Paige Becker took it last year in Lady Lake, Florida.

“For me, it wasn’t too much because I love the course,” she says, “but I know not everybody’s a history lover.”

She had to read about 30 pages every night, analyze documents, write essays and take lots of tests to prepare for the big exam. After she took it, she went online to look at the website for the College Board — the nonprofit that runs the advanced placement curriculum and exam — and saw an announcement that AP world history was going to change. Starting in the 2019-2020 school year, the class materials would begin in 1450.

“And I was like, ‘Wait, no, there’s more to history than that,’” Becker says. “That change would make it so that everything was cut out basically before colonization from Europe.”

Many teachers reacted that way too, because the change meant students wouldn’t learn about things like the Golden Age of Islam, the rise of mathematics in India, the innovation of Chinese dynasties or the great West African trading kingdoms.

At a conference in June, teachers confronted College Board Senior Vice President Trevor Packer. Amanda DoAmaral, who taught AP world history in Oakland, California, for five years, told Packer he was sending the wrong message to students of color.

“The people in power in our country already are telling those same students that their history, that their present, that their future, doesn’t matter,” she said. “And by you making this decision, you are going along with that. Their histories matter. Their histories don’t start at slavery.”

Packer said he was offended by that, and by people who suggested the College Board’s change to AP world history was financially motivated — because everyone would have to buy their new materials. Packer said he was just being realistic about how much information students could absorb in one year to prep for a $90 AP exam.

“If we wanted to increase revenues, we could make a very simple move,” he said at the conference. “It would be to take the two college courses that comprise AP World and create two separate world history exams: part one and part two.”

But that’s what they ended up doing.

“There’s no longer going to be one big AP world history course,” Becker explains. “It’s going to be split up into modern history and AP ancient history.”

Becker got this news earlier than everyone else. She and another student in New Jersey — Dylan Black — connected over the internet and started a change.org petition. More than 12,000 people signed, asking Packer not to change AP world history.

“I guess I just annoyed him enough that he finally contacted me,” Becker says.

The two students got on the phone with Packer, and he told them the College Board had decided to change course. The College Board would create another AP class to cover history before 1200. And the existing AP world history class would start at 1200, instead of 1450.

“And we both agreed that it was a much more acceptable change,” Becker says, “because you can go more into detail rather than keeping them really basic and general.”

The College Board says it won’t benefit financially from the changes, but declined to comment further.

Peter Stearns, of George Mason University, has been involved on and off with AP world history since its development.

Stearns says starting at 1200 isn’t ideal — but at least this way students will learn about a few cultures before they were conquered.

“It’s important to be realistic,” he says. “I support the change because I think they’re trying to satisfy a number of different constituencies and I honestly believe this is the best we will get. I have no reason to suspect [the College Board’s] motives.”

But for many schools, it’s hard to add another AP class. Stearns isn’t sure how many will take the time or have the resources necessary to offer the new AP world ancient history class.

“I’m very skeptical that many schools are going to jump into the development of the second course,” he says.

And that means many AP teachers across the country remain skeptical that the College Board should be making any changes to AP world history.

Eric Beckman’s taught the class for five of his 30 years in St. Paul, Minnesota, schools.

“AP world history had a lot potential to be a tool to kind of interrupt institutionalized racism,” he says. “And now this diminishes that.”

Beckman says cutting back on the time period covered by AP world history doesn’t make sense because the class is supposed to look at long-term trends in how history unfolds.

“When the president referred to the homes of some of my students as shitholes, I just want to publicly say I’m glad families are here,” Beckman says. “It’s a lot easier to say that having spent time talking about some of the golden ages in those parts of the world.”

Teacher Amanda DoAmaral says reframing AP world history may influence how students think about themselves.

“When you grow up as a person of color in this country and you learn about your history as beginning with oppression it paints a picture for you, that your history has always been one of oppression,” she says. “And then it normalizes that — it becomes ‘that’s the way things have always been and that’s the way things will always be.’”

But DoAmaral says she still doesn’t feel like educators are being heard.

“I think that’s that’s exactly the same issue that’s happening across the country,” she says. “It’s like people are just frustrated and can’t get things changed because we’re not being listened to.”

Becker, the Florida student who’s going to be a junior in the fall, thinks teachers might be over-reacting. She says the creation of a new AP ancient world history class solves many issues, even though it may take a few years before the course shows up in schools.

“All these teachers are upset — they’re like, ‘Oh, that’s still Eurocentric.’ Well, it’s AP modern history; they’re not trying to say it’s world history anymore,” Becker says. “That’s the main thing I was having an issue with.”