Migrant family reunification slowed by tech issues

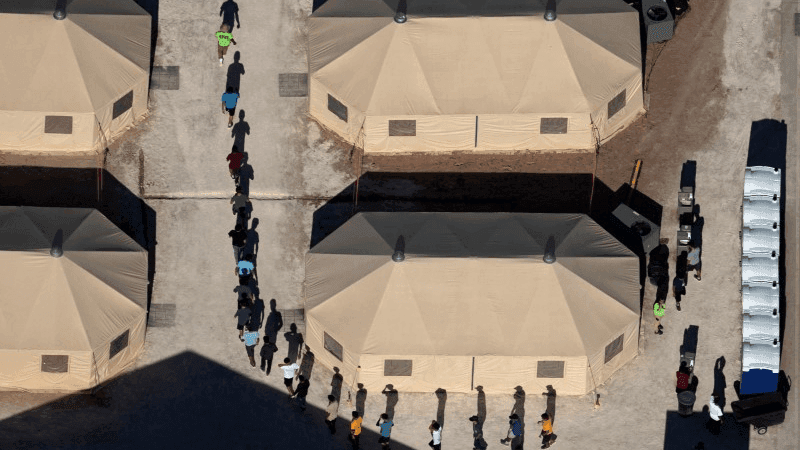

Immigrant children now housed in a tent encampment under the new “zero-tolerance” policy by the Trump administration are shown walking in single file at the facility near the Mexican border in Tornillo, Texas, June 19, 2018.

In late June, attorney Sebastian Harley tried to log into a US government web portal to check on a Guatemalan child who had been separated from his parent at the border. He got an error message saying there were too many users.

“I just couldn’t get in,” he said. “The system appeared to be down.”

It was not an isolated incident. From the moment it went online in January of 2014, the computer system designed to track unaccompanied immigrant children and process their release has created headaches for the shelter staff, government employees and others who use it, according to interviews with a dozen current and former users, government reports and congressional testimony.

Users described a frustrating array of issues, including that the portal could only handle a limited number of users at once without crashing, lost saved data, had poor searchability and required significant manual work for even small updates.

Now that system, operated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) and known as the UAC portal, has become a key part of the effort to track thousands of children under government supervision who were separated from their parents by immigration officials in recent months. It is being used by government employees, legal service providers, shelter workers and call center operators looking to answer parents’ questions about their children’s whereabouts.

But the system was set up to track unaccompanied minors rather than those separated from their parents by border officials, and it has little ability to interact with the separate database used by Immigration and Customs Enforcement to track the children’s parents, users said, complicating efforts to easily link family members.

One caseworker involved in reunification efforts said she has used the portal regularly over the past eight months, and that “for some weeks during that period, it was making our daily work impossible.”

A Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) official said the UAC portal is what call center workers use to locate children in ORR custody. The agency is “constantly making improvements to the portal,” he said, but did not provide further details.

Paige Austin, an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union, said she and her colleagues have documented numerous cases this year in which issues with the UAC portal delayed the release of children from ORR custody.

“We definitely observed that issues with the portal were an impediment to finalizing release and referrals,” said Austin.

The portal’s shortcomings are just one of many challenges that have cropped up as the government races against court-imposed deadlines to reunite children and families it has separated at the border.

Federal judge Dana Sabraw ordered the reunifications after the American Civil Liberties Union filed a San Diego lawsuit challenging the government’s policy of separating children from their parents. In his order setting a July 26 deadline for reuniting all separated families, he noted that while the government routinely catalogs detainees’ possessions, it “has no system in place to keep track of, provide effective communication with, and promptly produce alien children.”

A trail of problems

Issues with the computer system have been repeatedly documented.

In October 2015, HHS data analysts told a US Senate subcommittee that the portal had shortcomings the agency was “working to fix.” Users had to be extremely specific when entering a name or address, for example: an entry for a street name including “Pl” is not the same thing as “Place.” And a minor misspelling of a name could mean a search would come back with no results, they told the committee.

The next year, a report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that ORR still did not have the processes in place to ensure data were reliable, systematically collected, and compiled in a useful manner.

Related: Chronic insomnia plagues young migrants long after they reach their destination

Michael Weiss, chief operating officer of the system’s initial developer Patriot LCC, said the government’s needs changed drastically from September 2013 when his company won the contract to build the first iteration of the system.

“They gave us very minimal requirements to get something up and running that they could at least use internally in their office,” he said.

After the system was launched, “they kept changing their requirements,” said Weiss, necessitating frequent updates. Still, he said, the company was unaware of any issues with the system beyond the usual software bugs. From 2013 to 2016, when Patriot’s contract ended, the company met or exceeded ORR’s requirements, he said, according to evaluations it received.

In mid-2016, a government agency known as 18F, which does small-scale technology projects, was brought in to help strategize how to manage increasing demands on the system and address its problems.

Related: In New York, volunteers engage in a quiet form of advocacy for immigrants facing deportation

The homepage took minutes to load, even without heavy traffic, and the system would crash if too many people logged on at once, said former 18F developer Kane Baccigalupi. “There were really significant performance problems.”

For one thing, she said, caseworkers who wanted to add to or fix a child’s record had to copy what was in the fields before they went into edit or else information would be deleted.

Baccigalupi said her team ran out of time to address system-wide problems and instead focused on building a feature that allowed users to check bed capacity. When the developers’ contract ended around the time of the 2016 presidential election it was still “not a working system,” according to Baccigalupi.

The HHS official said upgrades to the portal were made in 2016 to refine the process for entering addresses and add the bed capacity feature.

Problems persisted

A former government contractor who used the portal daily from when it launched until June 2017 said the system made it difficult to find children with multiple last names, which are common in Latin America, or to search for different spellings of names such as Cortez and Cortes.

“If you have the wrong one, it’s not going to find anything,” he said. He described working around the system by putting in different combinations of names until he found the child he was looking for.

When he went to edit or update a child’s file, he said, he learned to save the information in a separate document on his computer in case the system crashed or the information did not upload correctly. “I wanted a Word document to make sure I had it,” he said.

Currently, Pennsylvania-based Applied Intellect has the contract for operating the portal. The company referred requests for comment to HHS, and it is unclear what work has been done since Trump took office in January 2017.

A GAO report this year noted some improvements by ORR in “systematically collecting information that can be used internally and shared, as appropriate, with external agencies,” such as more timely and complete record keeping of the quality of care children received after they leave ORR facilities.

But the report also found that as of April, “case management functionality had not yet been built into ORR’s web-based portal,” a crucial component for tracking the care of children.

Kathryn Larin, who directs the GAO’s education, workforce, and income security team, said that as of April 2018, caseworkers maintained paper files for children and the data were not always entered into the UAC portal. Caseworkers often collected information in their files which did not fit readily into the portal’s data fields, she said.

A day after attorney Sebastian Harley was unable to log in to the portal, his colleague was able to get an update on the Guatemalan boy — by calling the child’s caseworker.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?