Support for refugees increases when refugees participate in integration programs

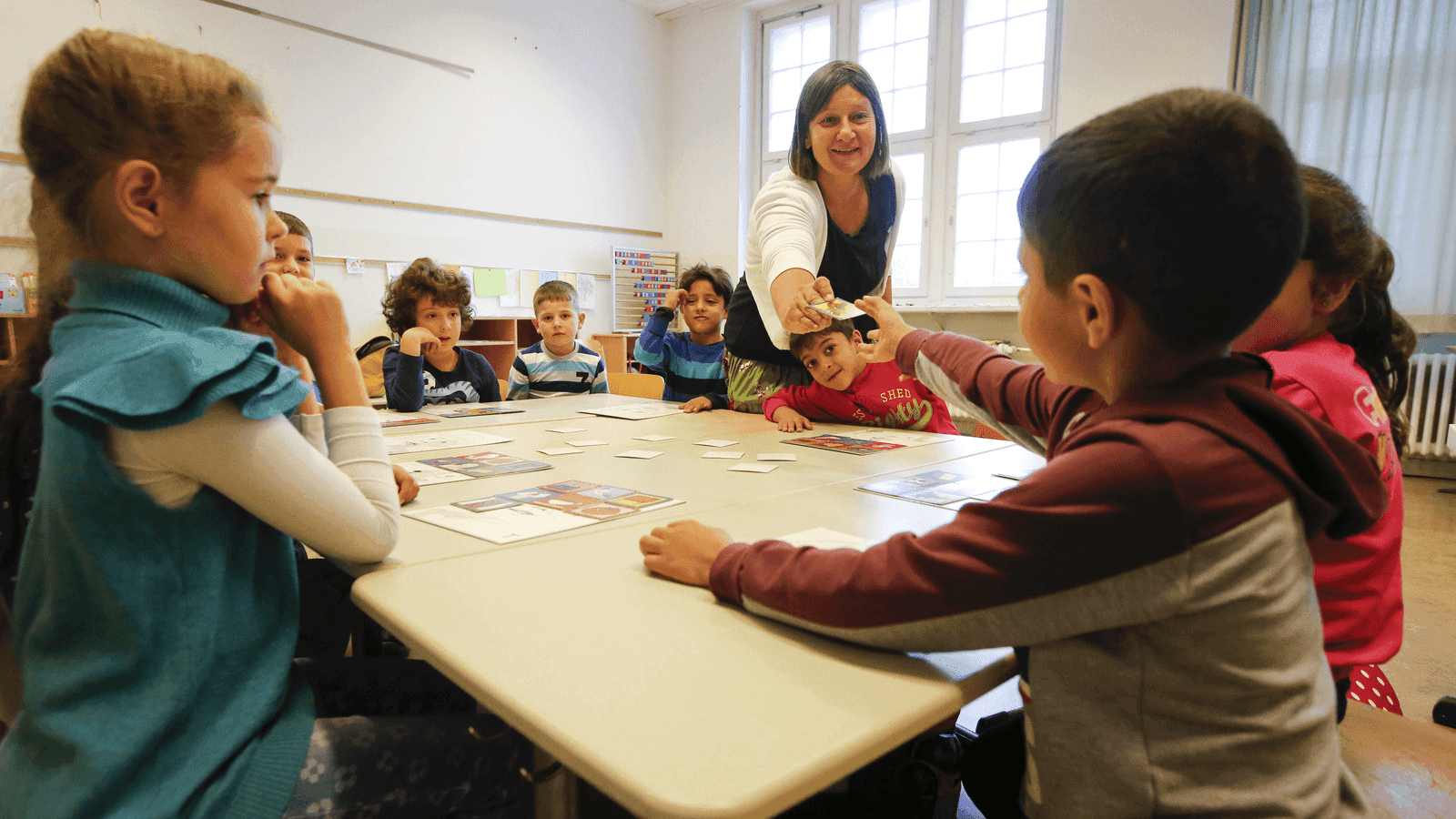

A teacher conducts a German lesson for children of a welcome class for immigrants at the Katharina-Heinroth primary school in Berlin, Germany, Sept. 11, 2015.

The executive branch has a fair amount of power to open or close US borders, as the US Supreme Court confirmed in its recent decision to uphold President Donald Trump’s travel ban.

But ultimately, as in most democracies, a country’s leadership needs at least some support from citizens for its decisions. What influences how people feel and think about refugees, and how willing they are to help?

Some research suggests that it depends on how well refugees are able to integrate into their host country. Refugees and other migrants coming to Germany, for example, are required to take integration courses — 600 hours of German language classes, as well as 100 hours of classes that cover the German legal system, history and culture.

According to the Migrant Integration Policy Index 2015, which uses numerous indicators to measure how much migrants are participating in society, Germany is doing very well. This is particularly true of integrating migrants into the German workforce.

We are scholars who study trust and cooperation between people. In a series of studies we conducted with other colleagues, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we found that citizens become more supportive — even willing to spend more of their tax money for refugee helping — if refugees are able to show that they are making an effort to integrate.

The ‘refugee game’

To model the refugee crisis for our study, we developed the “Refugee Game.”

For decades, scientists have used so-called “economic games” to model social issues in a laboratory setting. In these games, study participants are faced with a conflict of interest between their self-interest and the interest of the collective.

In our study, we invited more than 350 German participants to play different versions of the Refugee Game in an interactive computer laboratory.

In some variations of the game, we changed how costly it was to welcome and support refugees. For example, welcoming a greater number of refugees would pinch players’ pockets to simulate the costs of tax dollars going toward such programs. We also varied the neediness of the refugees, by changing whether they entered the game with a financial loss or not.

Moreover, we varied how much time and energy the refugees must invest into integration upon arrival, for example, by taking courses in the language and culture of the host country.

Ultimately, our goal was to find out whether variations, such as how needy refugees are or whether refugees must take integration courses, will influence participants’ helping, at a real cost to themselves.

Benefits of integration

Our results showed that citizens’ willingness to help refugees decreased as the personal financial cost to the citizens increased. At the same time, willingness to help increased when refugees were presented as being in great need.

Most striking was that players were much more prepared to pay — by allocating a greater amount of tax money to refugees — for the costs of welcoming refugees when a mandatory integration program for refugees was adopted.

This may be for two reasons. One is that by following integration courses, refugees can communicate positive intent to the host citizens to build a constructive future in the host country. Another is that by adopting a mandatory integration policy, a country also communicates positive intent: a strong commitment to invest in the future of the refugees.

The positive effects of such integration policies may be lasting. One-on-one contact between individual refugees and citizens has been found to reduce prejudice and promote further acceptance and respect.

As social psychologist Linda Tropp has suggested, the positive effects of contact are even more likely if people share the same goals.

For example, in the Netherlands, electricians are badly needed but refugees are often not hired because they do not speak Dutch well enough. This form of working together could more easily be fostered if refugees mastered the language, promoted by an effective integration policy.

![]() Promoting a more positive outlook on refugees among citizens may also involve storytelling. Our research suggests that when refugees and their children overcome adverse and precarious circumstances, citizens are more supportive and accepting. The same is true when they hear about the hard work it takes for refugees to integrate. Telling these stories in detail could help increase support and acceptance among citizens.

Promoting a more positive outlook on refugees among citizens may also involve storytelling. Our research suggests that when refugees and their children overcome adverse and precarious circumstances, citizens are more supportive and accepting. The same is true when they hear about the hard work it takes for refugees to integrate. Telling these stories in detail could help increase support and acceptance among citizens.

Paul van Lange is a professor of psychology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Robert Böhm is an assistant professor of decision analysis at RWTH Aachen University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?