Medical or funeral insurance? More Zimbabweans choose to secure death over health.

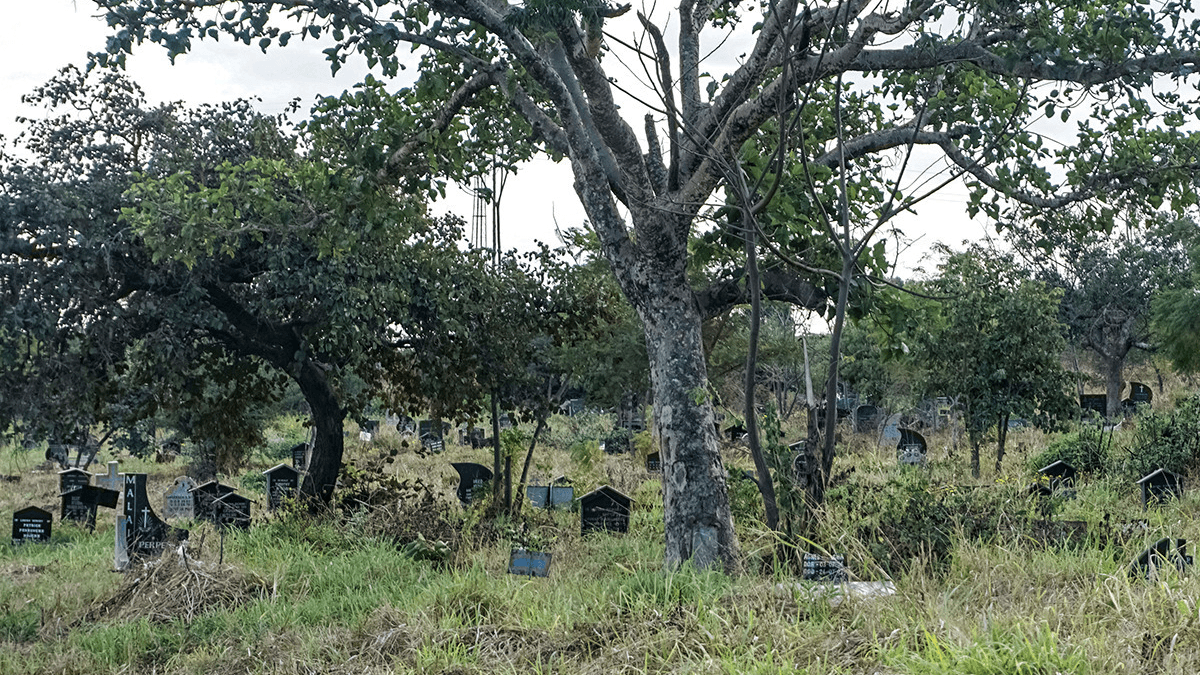

Many Zimbabweans choose funeral insurance over medical insurance, to guarantee that they’ll be able to afford gravestones, funeral services and other details that are expected here. Pictured is a cemetery in Mutare, Zimbabwe.

Cellphone minutes are in constant demand, so Susan Musungambira, who sells cards that replenish those minutes, has no problems with job security.

But her income is another issue. Musungambira doesn’t earn much, so she has to make tough choices.

One tough choice? To forgo medical insurance.

“We actually joke that a vendor shouldn’t get sick, as we cannot afford to get sick,” she says.

And yet, Musungambira has enough money to buy funeral insurance. In a culture where a funeral is often an expensive but required, days-long affair rich in meaning, she feels that it’s important to prepare.

“Given a choice, a funeral policy is better, because death is untimely, and funeral expenses are more than health expenses,” she says.

She’s not alone. The majority of Zimbabweans aren’t insured at all, but most who do carry insurance have it to cover expenses incurred for their last rites, rather than for medical costs that might otherwise keep them alive.

Just 30 percent of adult Zimbabweans have any form of insurance, according to 2014 research conducted by Finmark Trust and published by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. Of those people who are insured, 82 percent have funeral insurance.

Estimates by the Association of Healthcare Funders of Zimbabwe show that the situation is perhaps even more dire. A 2017 report noted that 1.3 million people — out of 14 million people in Zimbabwe — have medical insurance. That’s about 9 percent of the total population. (Some estimates note that Zimbabwe’s population is closer to 16 million.)

Medical insurance, often called medical aid in Zimbabwe, costs anywhere from $15 to $100 per month, depending on the plans and the services they provide.

Funeral insurance, on the other hand, can cost as little as 50 cents per month for a basic plan.

Traditional insurance companies offer policies that cover funerals, but often it’s funeral homes themselves that act as informal insurers throughout Africa, according to research published in 2011 by the Microinsurance Innovation Facility, a division of the International Labour Organization. Funeral insurance is especially popular in South Africa, where an estimated 45 percent of adults have policies. Last rites are a high priority in that country, even when they’re expensive.

The same is true in Zimbabwe, but with a serious, years-long economic crisis stunting daily life, people sometimes struggle to gather the money needed for even their most important traditions.

Zimbabwe’s unemployment rate is debilitating. Exact numbers are disputed, but some estimates note that it might be as high as 90 percent. Many of the people who are employed work in informal sectors. Jobs that offer benefits are rare.

Even for people who can afford insurance coverage, there’s not much motivation to pay into a system that might not be around when they need it.

In 2009, when Zimbabwe introduced a multi-currency system, crushing inflation came with it. Life insurance policies were wiped out, along with the life savings of many people.

Now, as Zimbabwe’s economy still struggles to stay afloat, some doctors no longer accept medical insurance, because they don’t get paid by the insurance companies, they say.

Dr. Enock Tatira, a general practitioner in Mutare, says doctors are forced to pay taxes to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority on money that they haven’t received yet.

“Many practices folded as a result, and the remaining ones started asking for cash payments from patients,” Tatira says.

When it comes to funeral insurance, the low price makes it affordable for Zimbabweans who want to plan ahead for future financial needs but who otherwise can’t afford to do so.

Mildred Matwenyu is a vendor who sells soft drinks and sweets — a job that offers little money for expenses other than basic necessities. She bought a funeral insurance policy that, for $36 per month, covers her and her children.

“I would want to have medical aid insurance … but with no salary and fixed income, there is no guarantee I would be able to pay every month,” she says.

If she has more children, she says, she’ll simply add them to her funeral insurance policy.

Evidence Chenjerai of GPJ translated some interviews from Shona.