The liberal ideal that died with Robert Kennedy

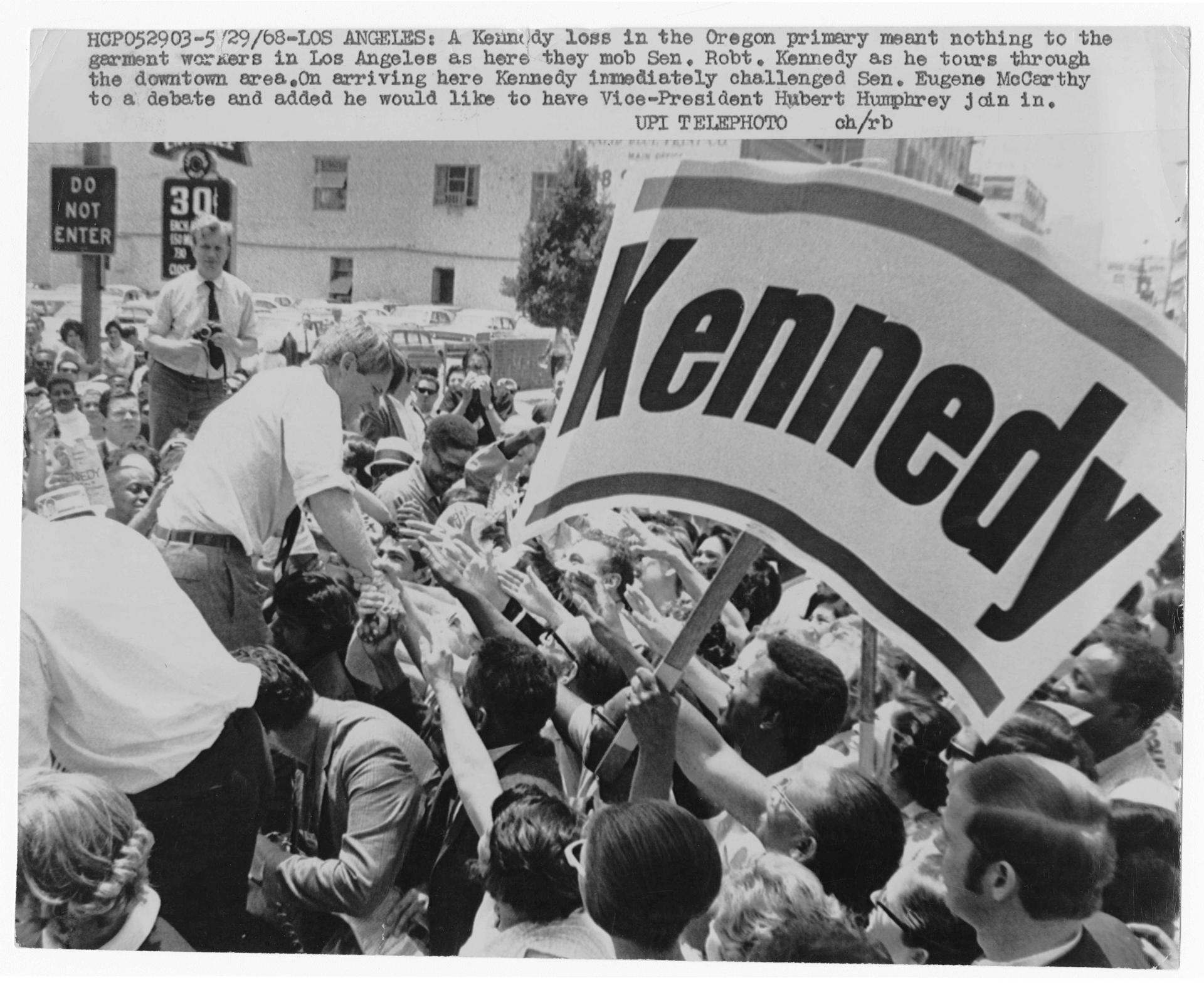

A contact sheet of photos taken by photojournalist Ron Bennett of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy campaigning in 1968 to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee. Challenges to the sitting president, Lyndon B. Johnson, by two members of his own party, Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy, turned the Democrat primaries into a de facto referendum on the unpopular war in Vietnam, especially after Johnson’s shocking announcement that he would not seek re-election. Kennedy entered the race in opposition to the Johnson administration’s Vietnam policy and as a progressive voice on urban and racial issues. “It was always a long shot for Kennedy,” Witcover says. “[But] he was a sensation in the campaign … generating so much enthusiasm and support.”

The words “blood” and “Oh my God” stand out among the indecipherable scrawl of hurried writing on two pages of a 50-year-old notebook that belonged to journalist Jules Witcover.

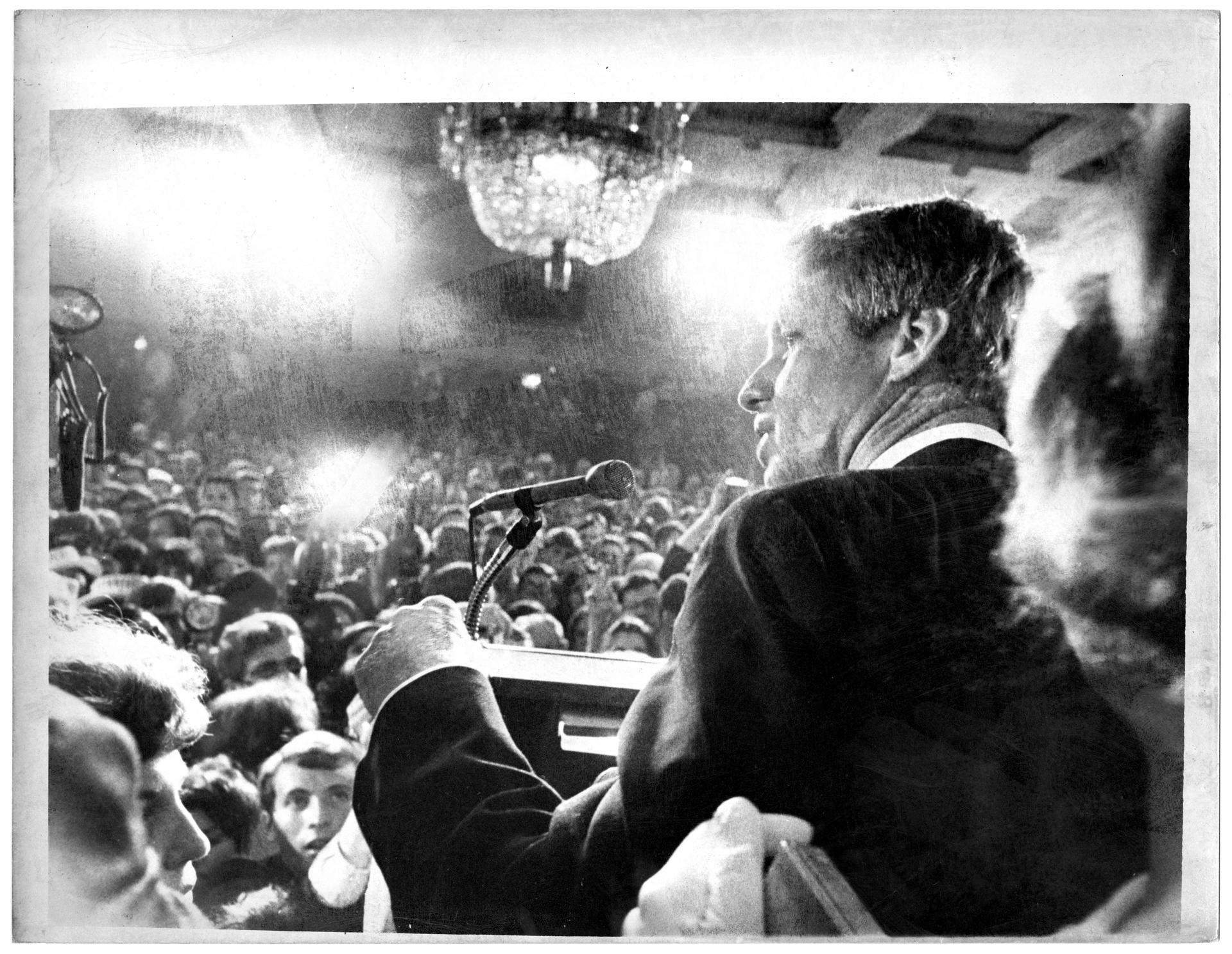

Late at night on June 4, 1968, Witcover had listened to Senator Robert F. Kennedy give a rousing victory speech at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles after winning the California primary in the race to become the Democratic nomination for that year’s forthcoming presidential election.

Following the speech and just after midnight, Witcover and other members of the press followed Kennedy and his entourage through the hotel’s kitchen passageway toward another room where the senator would give a press conference.

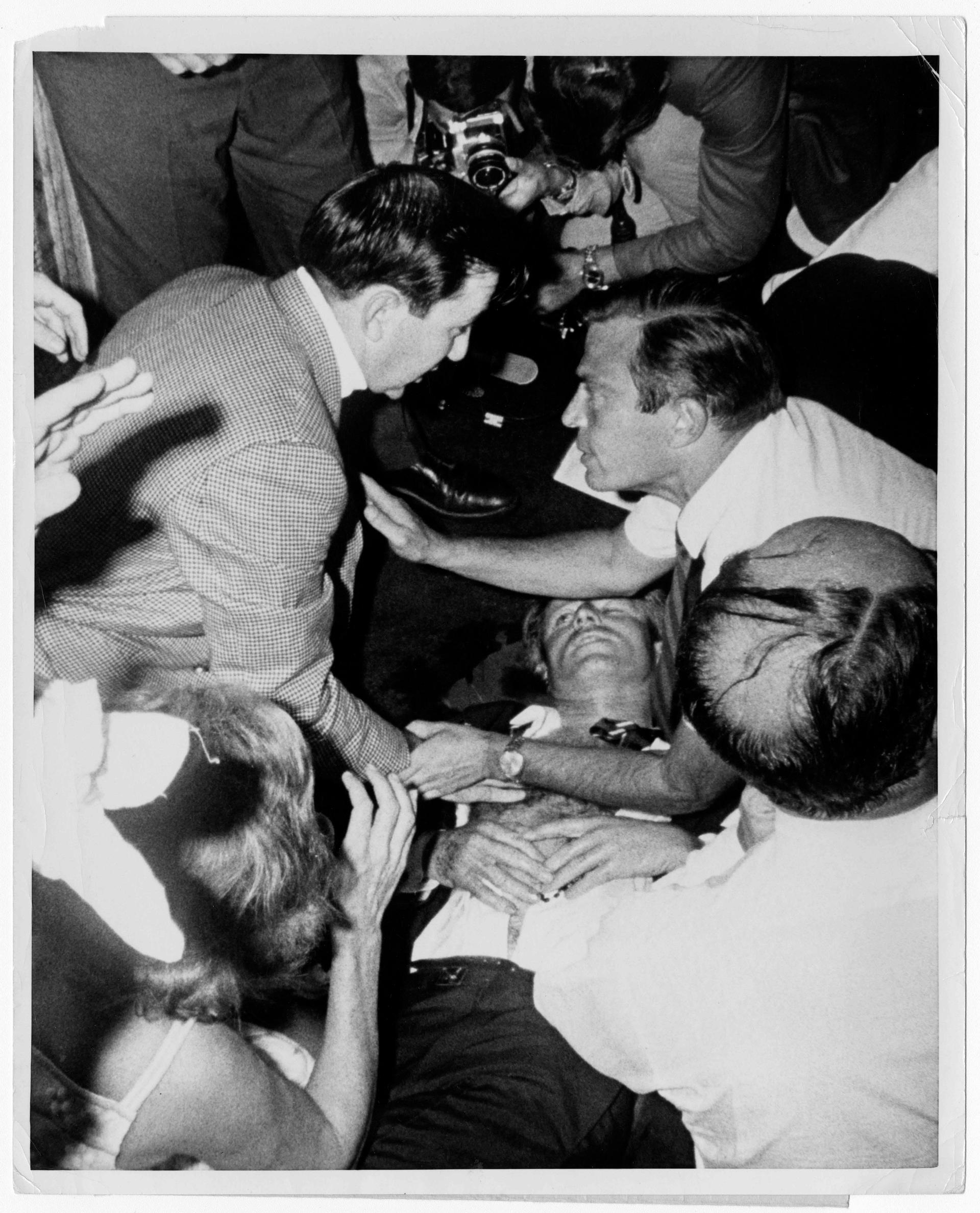

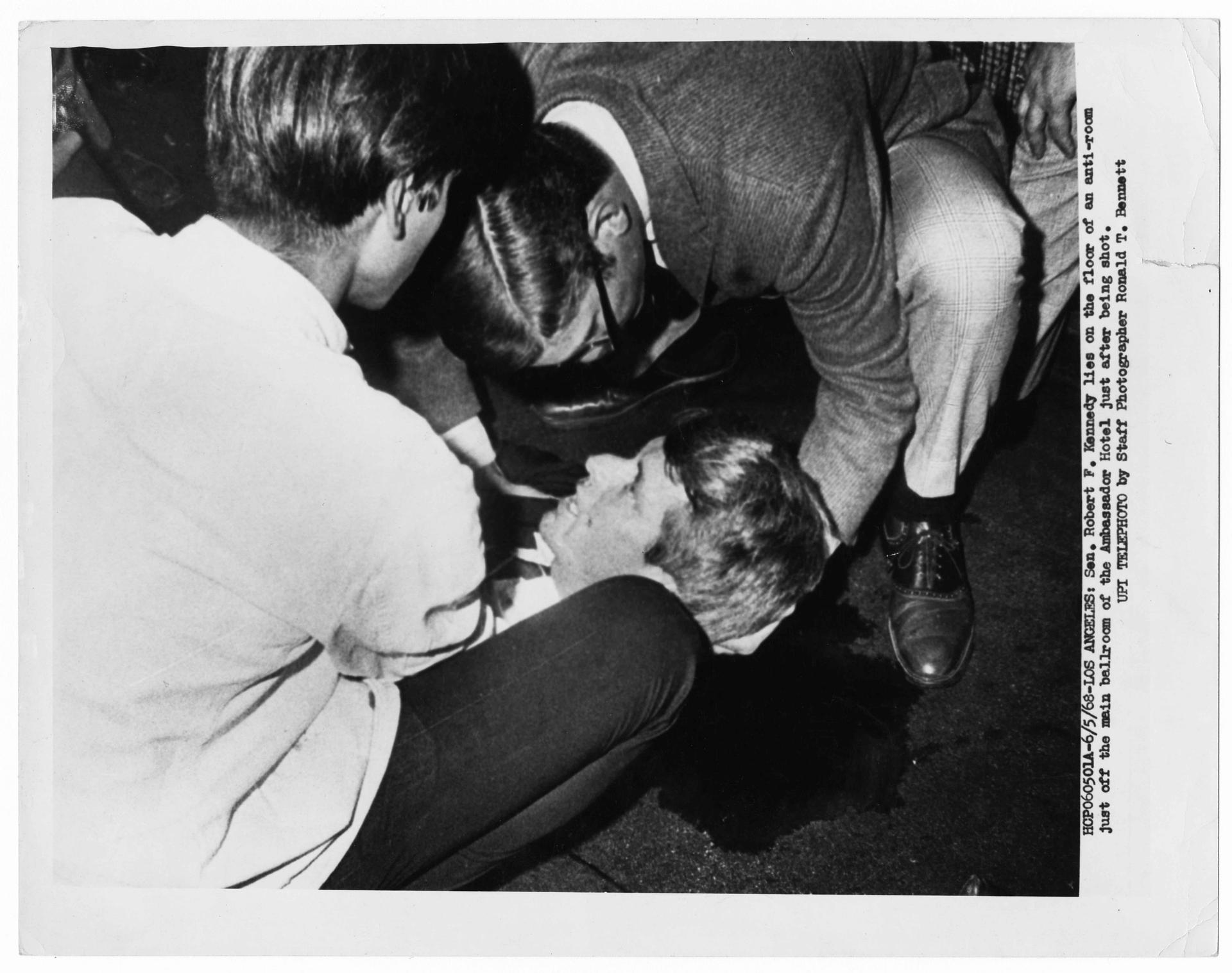

“This young man was poised by one of the steam tables and as Kennedy came through he reached forward and shot him,” Witcover says. “I turned and saw Kennedy falling — the place [became] bedlam, people screaming, shrieking and crying. He was conscious; he lay there with his eyes open, but was obviously on his way out.”

Kennedy died of his wounds 26 hours later in the early hours of June 6, a tragic end to one of the most interesting political careers in modern American history. His death came two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.— two shattering events that continued that spiral of violence that had dominated the 1960s, plunging an already dismal year into further darkness against the background of the Vietnam War.

“It was one of those extraordinary benchmark years,” wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and chronicler David Halberstam. It “seemed to signify that the country, under the ferocious pressure of rapid technological change (most particularly, the nightly delivery of televised news into each home), the growing pain of an unwinnable war in a distant Asian society, plus bitter, increasingly explosive racial division, was on the verge of a national nervous breakdown.”

Later that year the Democratic National Convention in Chicago descended into anarchy and farce amid anti-war protests. The presidential election followed with the Republican nominee, former Vice President Richard Nixon, defeating the Democratic nominee, incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

The loss of such strong voices as Kennedy and King’s advocating traditional liberal policies also meant there was no one to counter the emerging criticism of those policies, allowing a conservatism — that only four years earlier had been firmly rejected in the presidential candidacy of Republican Barry Goldwater — to take root.

“What ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s was a set of policies of expanding rights [and] expanding government services and assistance for those in need,” says Jeremi Suri, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of “The Impossible Presidency.” “The backlash against that was facilitated by the absence of effective figures like Robert Kennedy.”

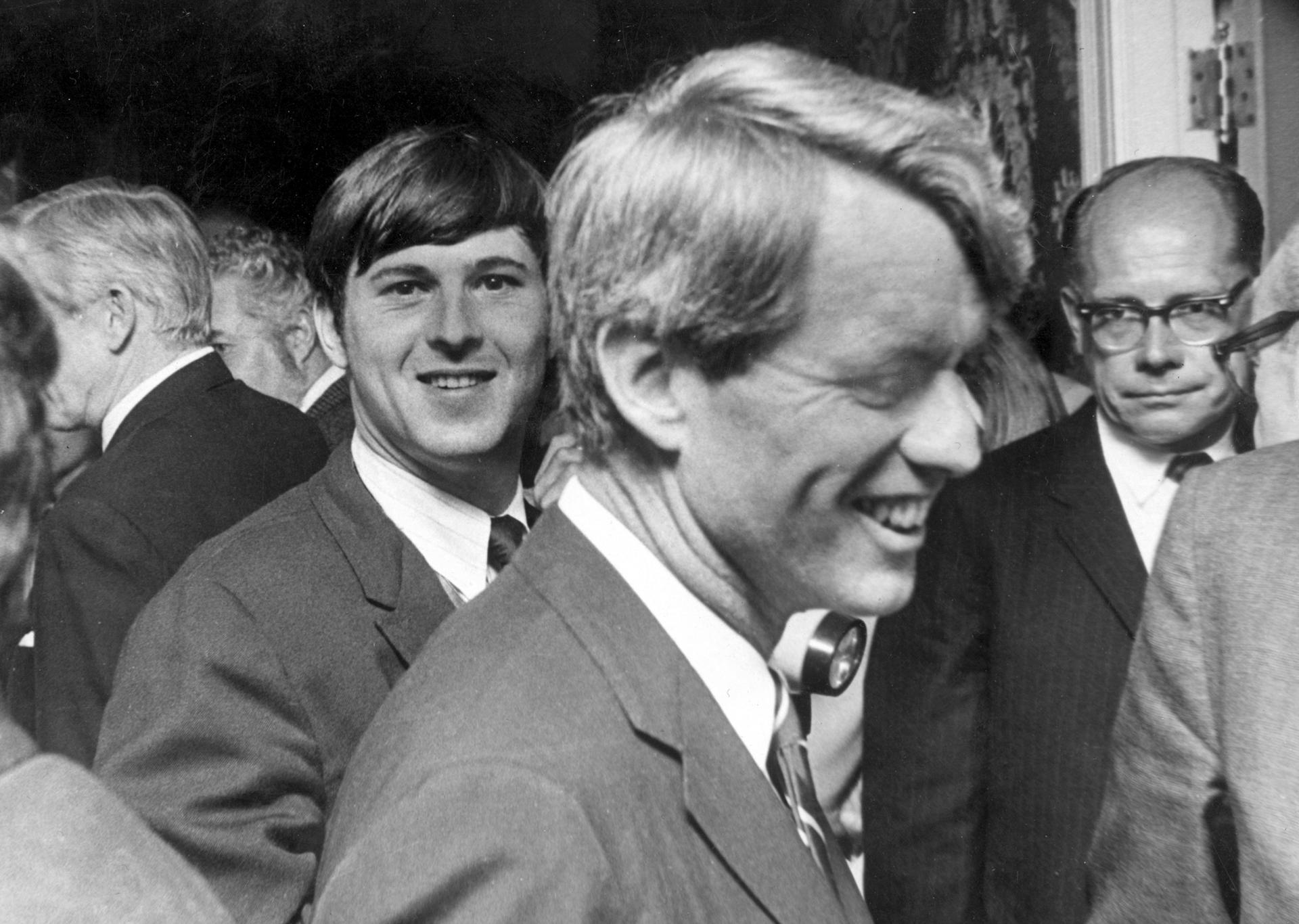

Robert Kennedy’s transformation

Robert Kennedy appealed especially to poor, African American, Hispanic, Catholic and young voters as an icon of modern liberalism who transcended the racial divide. He was also popular among the journalists covering him. “We had seen at close range his evolution from a rude, arrogant young brat as a favored brother of a prominent senator and a tough and abrupt campaign manager [for John F. Kennedy’s presidential bid] to a wrenchingly troubled heir to a political legacy that had increasingly taken him out of himself and made him a public man, espousing the public good,” Witcover wrote in his book “1968: The Year the Dream Died.”

A people’s person

Like Witcover, photographer Ron Bennett got to know Kennedy while photographing his campaign for United Press International. Bennett recalls how he enjoyed a cigar and a drink with Kennedy in the hotel’s VIP room before Kennedy made his California primary victory speech. “He was a good man, he loved people,” Bennett says. “He had a great following with Mexicans and blacks and whites.” During his time in office, Kennedy opposed racial discrimination and US involvement in the Vietnam War. He was an advocate for issues related to human rights and social justice and formed relationships with Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez.

Short-lived victory

Kennedy finished his California victory speech by saying “On to Chicago,” referring to the Democratic National Convention to be held later in the year. Despite the enthusiasm and momentum his campaign engendered, opinion remains split on whether Kennedy could have secured the Democratic nomination or managed to become president. “By 1968, the forces that were rising up in reaction against the Great Society, which was an extension of the New Deal of the 1920s, they were going to defeat whoever the Democrats put up,” says historian and author H.W. Brands. “So even if Robert Kennedy had got the Democratic nomination, I think he would have been defeated. It was a Republican year; Americans were disturbed and angered by all the violence of the 1960s and the failure of [two] democratic administrations to take the Vietnam War to a successful conclusion.”

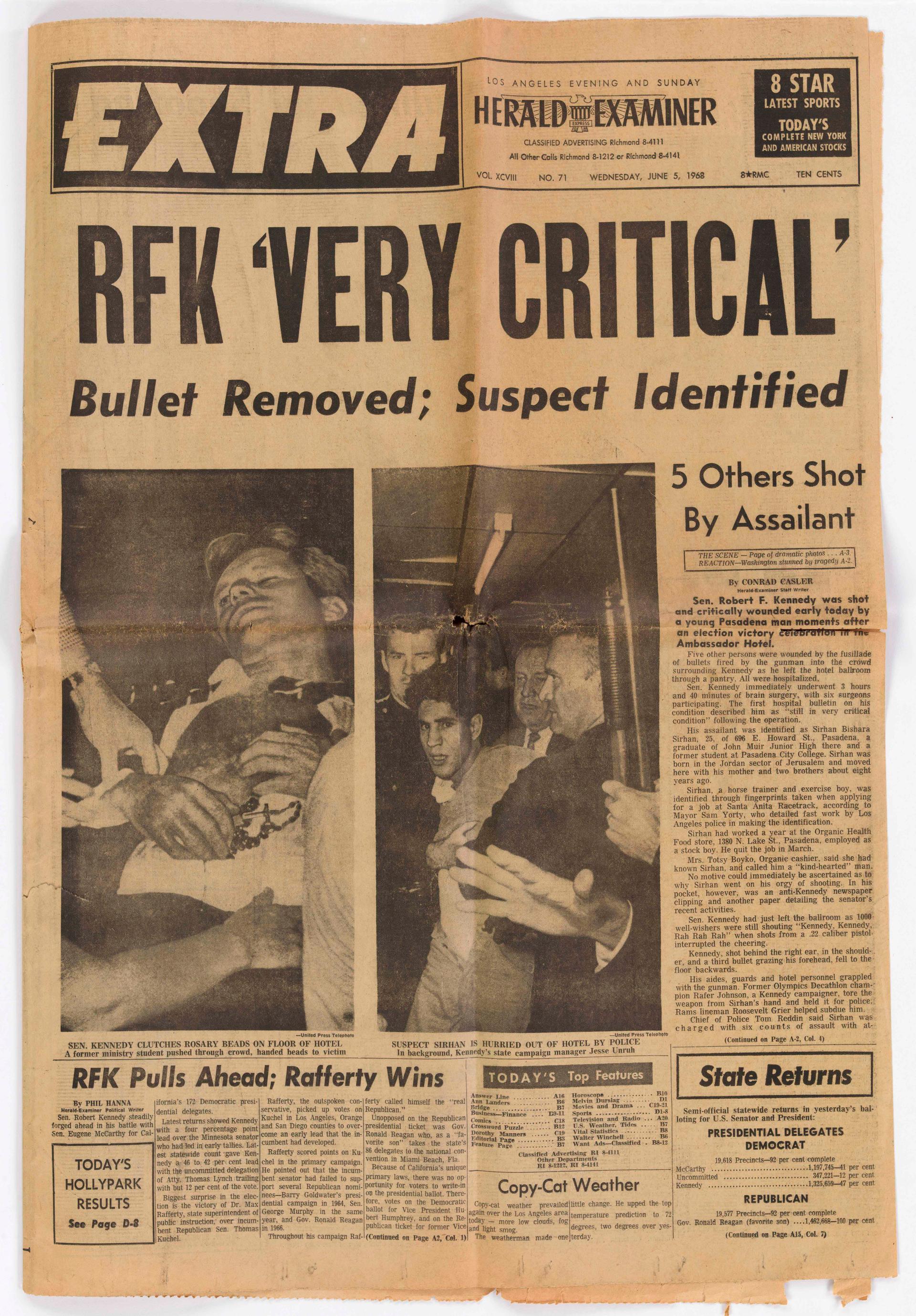

Another nightmare

One bullet lodged in Kennedy’s brain, another hit him in the back of his neck and a third grazed his forehead. The BBC’s American correspondent Alistair Cooke, who was at the scene, described how “on the greasy floor was a huddle of clothes and staring out of it the face of Bobby Kennedy, like the stone face of a child’s effigy on a cathedral tomb.” He also recorded: “I heard a girl nearby moan, ‘No, no, not again!’” and a dark woman suddenly bounded to a table and beat it and howled like a wolf, ‘Goddamn stinking country! No! No! No! No! No! No! No!’”

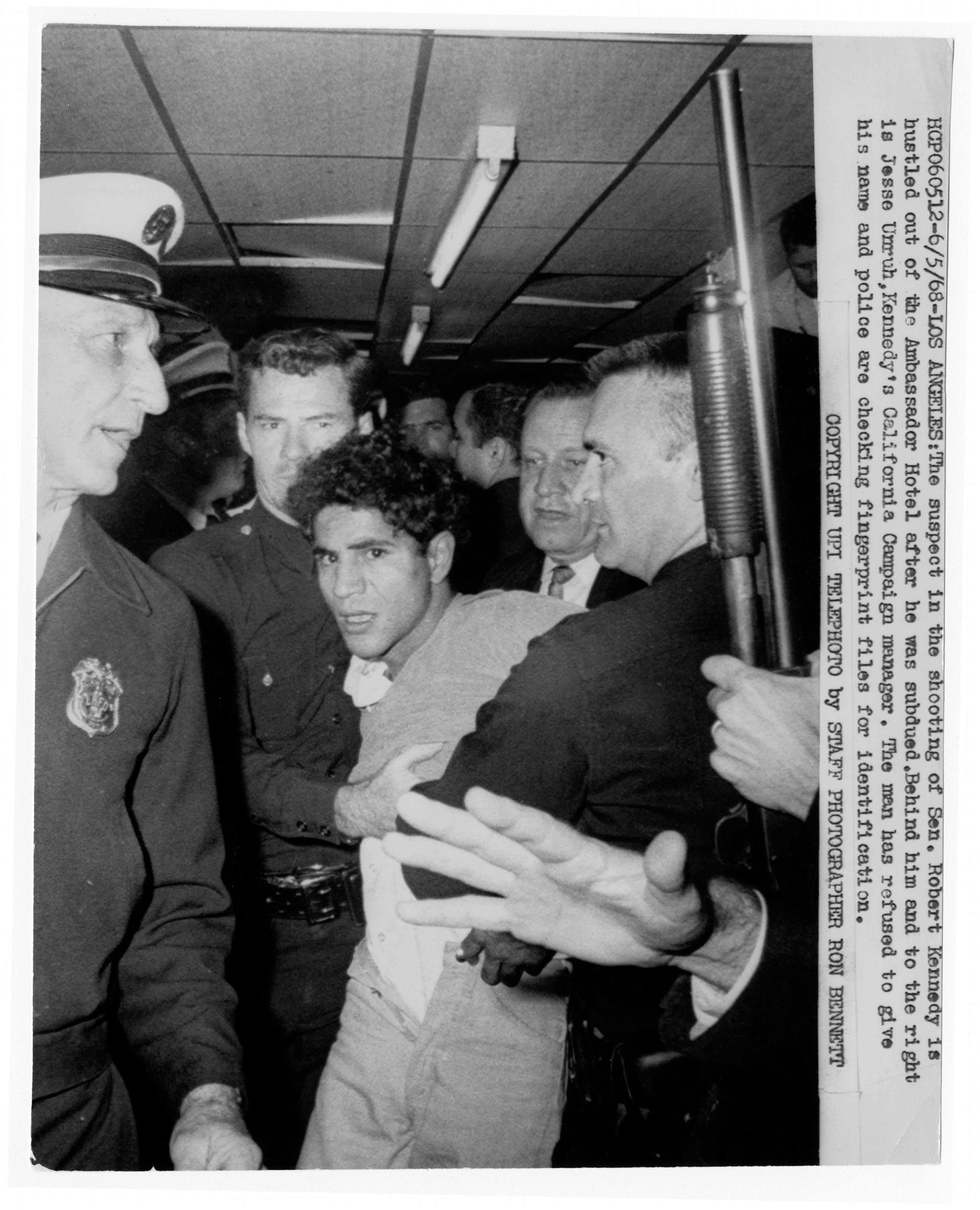

Hustled away

It emerged that the assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, was a 24-year-old Jordanian born in Jerusalem who had lived in the Los Angeles area since 1957. He attacked Kennedy for the latter’s pro-Israel stance. In notebooks found at Sirhan’s home, he wrote about the necessity to assassinate Senator Kennedy before June 5, 1968 — the first anniversary of the end of the six-day Arab-Israeli war.

Slipping away

Witcover recalls how a 17-year-old kitchen worker, later identified as Juan Romero, knelt next to Kennedy, took a set of rosary beads from his shirt pocket, placed it in Kennedy’s hand and prayed. “After what seemed like an interminable time but actually only ten minutes after the shooting, two medical attendants finally wheeled in a low hospital stretcher and placed Kennedy on it.” Kennedy said “Oh, no, no, don’t,” in obvious pain, as he was strapped onto the stretcher before appearing to lose consciousness.

Reverberations

“For people who did not live through those times it’s hard to understand the America of the 1960s,” says journalist and broadcaster Michael Goldfarb, explaining how it was a time both of violent upheavals and excitement and hopes for a better future. But Kennedy’s death, along with that of Martin Luther King Jr. and the other seismic events of 1968, set American on a course of disappointment, racial division and distrust in its leaders that persists today. “The dream of a nobler, optimistic America died, and the reality of a skeptical, conservative America began to fill the void,” Witcover wrote.