In the US, fairy-tale royal weddings clash with reality

School children in uniform wave Union Flags outside Windsor Castle ahead of Britain’s Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding, in Windsor, May 16, 2018.

Unless you’ve been living in outer space, you probably know that on Saturday, Prince Harry will marry Meghan Markle. Many Americans will be setting their alarms to wake up early to watch the wedding, and some are even flying to London to partake in the big day.

Of course, there are always those who insist that none of it matters.

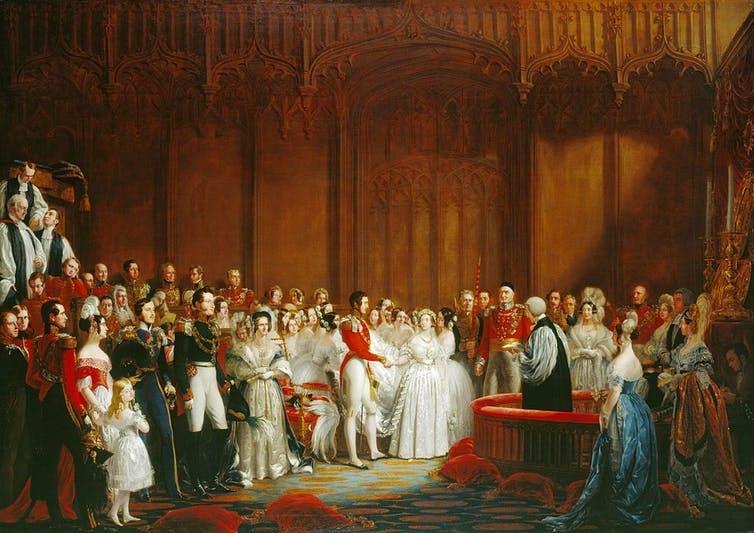

But royal weddings do matter. Since the wedding of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert on Feb. 10, 1840, they’ve shaped the expectations Americans have about their own nuptials.

In my book on romance and capitalism, I look at how engagements, weddings and honeymoons went from small affairs to spectacular, pricey events. Even though most Americans are unmarried, most of us would like to be. But marriage means a wedding, a ceremony that needs to be “perfect” in every way — an unrealistic standard that’s been shaped, in part, by what people see when they watch royal weddings and other celebrity weddings.

Like a Disney movie

At her wedding, Victoria wore a white gown, rejecting the traditional red dress. Within a few years, American women’s magazines were promoting the white wedding dress as a symbol of purity and innocence.

Victoria’s wedding was arguably the first celebrity wedding. It received massive media coverage, with stories circulated by telegraph to newspapers and magazines around the world. Upon learning about the trumpeters and the music, the glittering decor and luxurious attire, readers could imagine what a perfect wedding might look like.

Queen Victoria also wore a diamond engagement ring. Like the white wedding dress, the diamond engagement ring would eventually become a nearly mandatory item for a perfect love story. Of course, decades of clever advertising from De Beers also helped.

Fast forward to Charles and Diana’s wedding in July 1981. After decades of social upheaval and a sexual revolution, divorce rates in the US had peaked.

But Charles and Diana offered a public rebuttal to the social forces that were rejecting marriage. Their wedding played out like a Disney fairy tale, from Diana’s arrival in a white dress with a 25-foot train to Charles’ Prince Charming-esque military attire.

Around the world, 750 million people tuned in to watch the vows. In the US, spending on weddings soon began to climb.

While it’s hard to know whether the subsequent rise in spending on US weddings was tied to the royal ceremony, perhaps couples longed to mimic, in some small way, Diana and Charles’ dream wedding.

Any little girl can marry a prince

In 2011, the next royal wedding took this fairy tale narrative one step further when Prince William chose “commoner” Kate Middleton as his bride. Kate came from a middle-class background, and this was a central component of the media narrative.

I went to London for Kate and William’s wedding to conduct research for my book.

Nearly everyone I interviewed in the crowd that day talked about how the wedding gave them hope during troubled times. And a lot of the people I met were Americans. One young American woman told me she came all the way to London to see the wedding because it was a happy ending — and she needed happy endings.

“I don’t go to a movie unless I know it has a happy ending,” she said. “I don’t read a book unless it does.”

Another young American studying at Oxford told me, “It’s a true-life fairy tale, isn’t it? A commoner marrying a prince.”

Indeed, the couple followed the formula of any good fairy tale romance: An ordinary woman is plucked from her life in squalor by a dashing prince.

Now, with American Meghan Markle set to marry Prince Harry, another fairy tale plot twist is in the works. Meghan, who has a black mother and white father, shows that any little girl — no matter her race — can marry a prince.

It’s fitting that this royal wedding will take place exactly 50 years after Loving v. Virginia, which overturned bans on interracial marriage in the US.

Happily ever after … or not

The end? Not quite. Reality tells a different story.

Even as Americans might claim that love is blind, when we do marry, we continue to marry people who are pretty much like us — with the same education level, similar levels of earning power and mostly from the same racial background.

And even as Americans are spending more than ever on weddings, fewer and fewer are actually getting married.

Perhaps it is because many cannot afford their “perfect” wedding, so they’re simply putting off marriage. I’ve interviewed a number of couples who have already been living together, and maybe even have children together, but are just now getting married. The reason? They wanted to be able to afford their dream wedding.

But it seems that all of the time, energy and money spent on weddings isn’t actually making us very happy. In fact, research has shown that the more a couple spends on a wedding, the more likely it is that the resulting marriage will end in divorce.

In the 2017 World Happiness Report, economist Jeffrey Sachs wrote that Americans were looking for happiness “in all the wrong places.”

Attempting to mimic the luxurious pomp of royal weddings — as if it will somehow negate the work needed to make a marriage truly successful — might just be one of those wrong places. But it won’t stop many Americans from trying.

Attempting to mimic the luxurious pomp of royal weddings — as if it will somehow negate the work needed to make a marriage truly successful — might just be one of those wrong places. But it won’t stop many Americans from trying.

Laurie Essig is director and professor of gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Middlebury College.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.