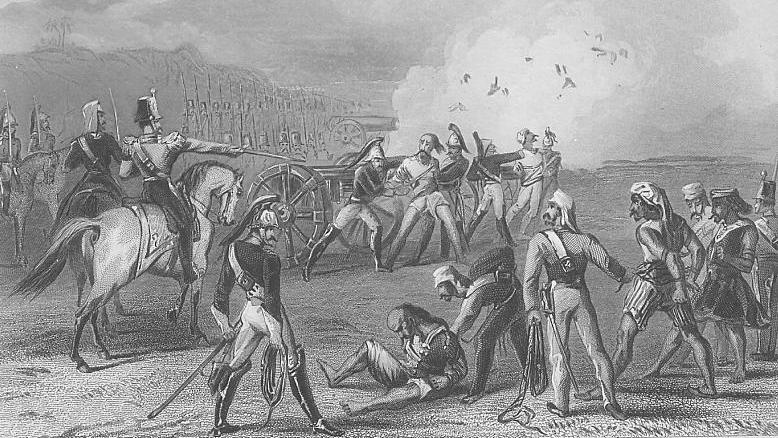

Indian rebels being executed by cannon, Sept. 8, 1857.

It’s not every day somebody brings you a skull. But for historian Kim Wagner this is exactly what happened one day in 2014.

“I received an email from a family who had a skull,” he says, “and didn’t know really what to do with it.”

The family had inherited the skull from parents who found it when they took over a the London pub, the Lord Clyde. That was back in 1963 and it made a local news story largely because of the note that was found with it.

“Skull of Havildar Alum Bheg,” the note begins, “who was blown away from a gun, amongst several others of his Regt. He was a principal leader in the mutiny of 1857.”

British historians used to call it the Indian Mutiny. Most Indian historians call it the First War of Independence. Wagner and other academics call it the Indian Uprising.

“It was perhaps the largest anti-colonial uprising in history,” says Wagner.

Wagner specializes in Indian colonial history and is a senior lecturer in British imperial history at Queen Mary University of London.

He began the long and difficult process of verifying the skull and story with it. His findings are published in a new book, “The Skull of Alum Bheg.”

It turns out Bheg was not “a principal leader” of the revolt. “Alum Bheg was in many ways an insignificant soldier,” says Wagner. “Just one amongst thousands who served in the East India Company army, but who got entangled in the uprising of 1857.”

The revolt failed and British retribution was savage.

Bheg was captured after a year on the lam. He was accused of murder and mutiny.

“At Sialkot, where Alum Bheg was, it wasn't as violent as was the case elsewhere,” explains Wagner. “But there was a Scottish missionary couple and a small baby who were waylaid and cut down. And that is one of the murders that Alum Bheg was alleged to have carried out.”

“As I found out in the process of researching the book,” Wagner says, “Alum Bheg was actually innocent but as far as the British were concerned it didn't matter much. Because all Indian soldiers — and in many instances, all Indian men in areas where the outbreak had happened — were considered to be guilty. With or without any evidence, really.”

Wagner’s story of Alum Bheg and the Indian Uprising is sensational, but he says his goal is different.

“My main aim with writing the book was to tell the world about the existence of Alum Bheg because nobody knows about him. But also, ultimately, to having [him] repatriated to India,” he explains. “But that's a rather lengthy and complicated bureaucratic process. But that is what I would like to see. I'd like for Alum Bheg to finally be put to rest in a respectful manner after he's been kept in various boxes and attics for more than a century.”

The book also comes out at a time when there's a lot of debate in Britain about the legacies of the empire and how to remember it.

“And my take is that you really cannot reduce the past to a simplistic binary of either good or bad,” says Wagner. “So, although my book describes in great detail a lot of horrific violence, at no point do I suggest that the British Empire in India was ‘bad,’ nor that it was ‘good.’ So what I would like for people to take away from a book like mine would be that it makes it difficult to be too proud of the empire when you remember these things.”

Wagner says, as a historian, he hopes that ultimately people have a more a more nuanced appreciation of the complexities of the past.

The Lord Clyde pub, by the way, is named after Colin Campbell, later the first Lord Clyde, a British general who played a leading role in suppressing the Indian Uprising of 1857.