22 million reasons black America doesn’t trust banks

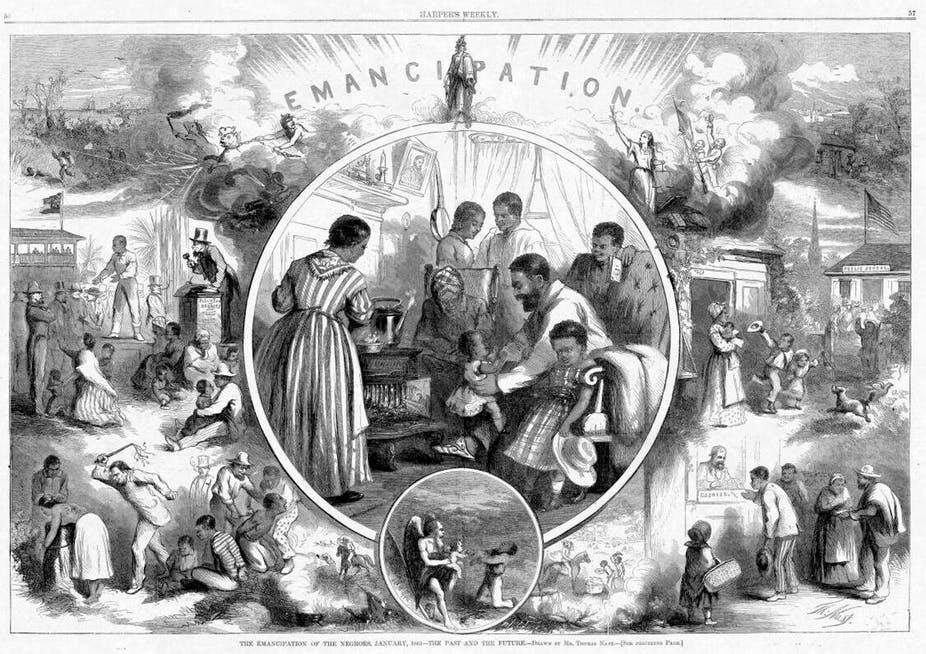

Emancipation is about financial security, too.

“This bank is just what the freedmen need,” remarked President Abraham Lincoln on March 3, 1865, as he signed the Freedman’s Bank Act, authorizing the organization of a national bank for recently emancipated black Americans.

A little more than a month later he was killed, making the Freedman’s Bank Lincoln’s last act of emancipation.

His assassination, however, did not impede its rapid growth. By January 1874, less than ten years after the establishment of the Freedman’s Bank, deposits at its 34 branches across the United States totaled US$3,299,201 ($65,200,000 in current dollars).

Despite such successful expansion, the Freedman’s Bank closed on June 28, 1874, under a shroud of suspicion and accusation.

The story of the rise and collapse of the Freedman’s Bank is an important and little-known episode in black and American history in the years following emancipation.

While it is widely known that there are severe disparities in wealth and income between black and white Americans, the origins of this are less appreciated. Indeed, before there was a Great Recession or a Great Depression, recently emancipated black Americans had their first monies as freed persons mishandled and never returned in full.

The genesis

Several issues led to the creation of the Freedman’s Bank: The emancipation of slaves, increased pay of black soldiers and migration of black Americans throughout the North and South.

Cases of black soldiers being swindled, for instance, were quite common, highlighting the need to establish a formal and central banking institution for newly freed blacks.

Following a meeting of key political and business leaders on Jan. 27, 1865, plans proposing the Freedman’s Bank were sent to the United States Congress, which swiftly approved the banking institution.

The subsequent outreach efforts by the bank’s initial president (and inspector and superintendent of schools for the Freedmen’s Bureau — the organization authorized by President Lincoln on March 3, 1865, to support and assist freedmen and freedwomen during Reconstruction) was a white Northerner named John W. Alvord.

Alvord, a former minister and attaché to General William Tecumseh Sherman during the Civil War, traveled throughout the South recruiting blacks using endorsements from General OO Howard (the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau): “as an order from Howard … Negro soldiers should deposit their bounty money with him.”

To assure possible depositors, Alvord also carried a handwritten letter from General Howard which read: “I consider the [Freedman’s Bank] to be greatly needed by the colored people, and have welcomed it as an auxiliary to the Freedmen’s Bureau.”

Success

Due to such recruiting efforts, the bank’s list of black depositors grew quickly, and soon 34 branches were established in locations across the country including New York City, Atlanta, Memphis, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., which also served as the headquarters.

“Go in any forenoon and the office is found full of Negroes depositing little sums of money, drawing little sums, or remitting to a distant part of the country where they have relatives to support or debts to discharge,”

remarked a reporter in 1870 in Charleston, South Carolina, amazed by the bank’s popularity.

Problems

By 1871, Congress had authorized the bank to provide mortgages and business loans.

Such mortgages and loans, however, were usually given to whites, creating a financial paradox — a bank using the savings and income of black depositors to advance the economic fortunes of whites who had at their disposal mainstream banks that excluded blacks.

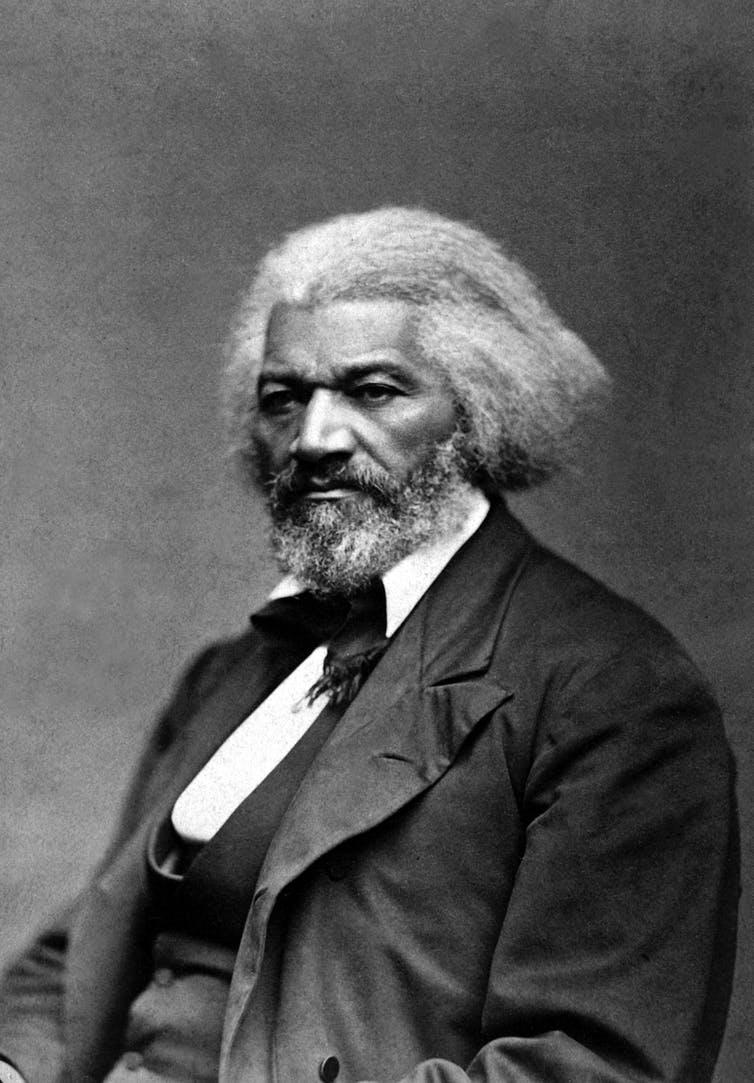

Soon reports and rumors of corruption within the bank’s white management threatened the bank’s existence. In response, the bank’s management was replaced with a variety of black elites, most notably Frederick Douglass, who was appointed to head the bank in March 1874.

These changes did not prevent the bank’s closing, with Douglass later describing the experience as being unwittingly “married to a corpse.”

Despite their usual disagreements, both W. E. B DuBois and Booker T. Washington did agree that the bank’s collapse was a major blow to the confidence and livelihood of scores of black depositors who trusted the bank with their savings.

DuBois would remark:

“Then in one sad day came the crash — all the hard-earned dollars of the freedmen disappeared; but that was the least of the loss — all the faith in saving went too, and much of the faith in men; and that was a loss that a Nation which to-day sneers at Negro shiftlessness has never yet made good.”

Booker T. Washington noted:

“When they found out that they had lost, or been swindled out of all their savings, they lost faith in savings banks, and it was a long time after this before it was possible to mention a savings bank for Negroes without some reference being made to the disaster of [the Freedmen’s Bank].”

By 1900 only $1,638,259.49 ($43,900,000 in current dollars), or 62%, of the total amount of deposits prior to the bank’s failure had been paid. Deposits worth some $22 million in today’s dollars were largely lost.

In the end, most black depositors lost their savings, receiving little to no money back from the bank or the federal government.

Echoes today

As we mark the 155th anniversary of the Civil War, the lessons of that era remain potent.

For its part, the story of the Freedman’s Bank reveals the important foresight Lincoln had in seeing a connection between the political freedom of black Americans and their financial security.

It also reminds us that to understand black banking and wealth today, we need to know some history.

Black wealth issues are not new problems. Rather, they are historically rooted in a persistent pattern of loss and mistreatment beginning with the mishandling of freedmen and freedwomen’s money during Reconstruction.

This is part of the promise of Black History Month, as it provides an opportunity to shine a light on not only the successes of black Americans but also on the roots of persistent patterns of unequal and unfair treatment endured.

Indeed, as we continue to carve a path through the aftermath of the Great Recession, the mortgage crisis and growing racial disparities in wealth, the history of the Freedman’s Bank can serve as an important reminder of the connection between financial and political freedom and mobility.

![]() Damage was done to black wealth and confidence long before banks were too big to fail.

Damage was done to black wealth and confidence long before banks were too big to fail.

Marcus Anthony Hunter, assistant professor, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.