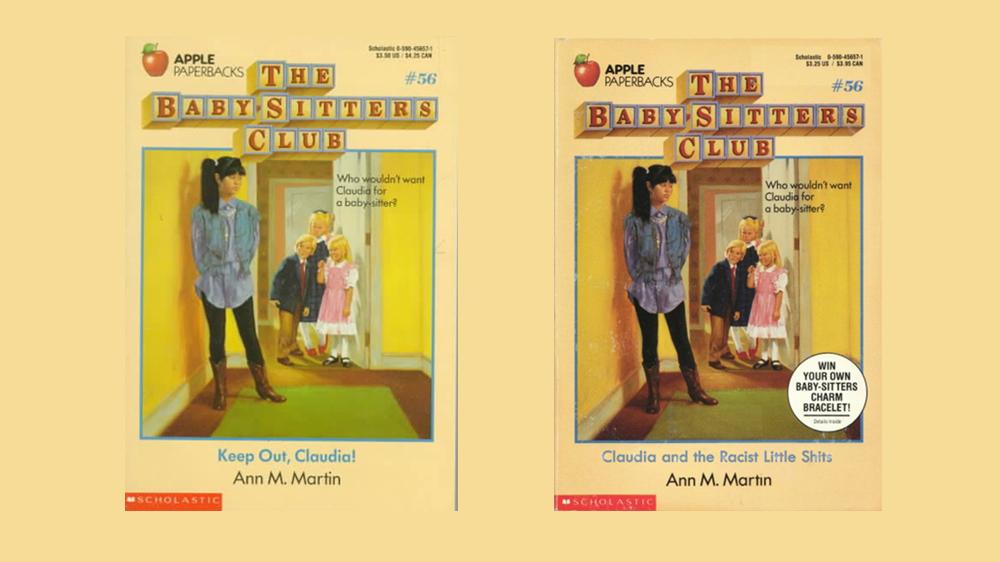

Blogger Phil Yu addresses racism directly in his remixed "The Baby-Sitter's Club" book covers.

Phil Yu still remembers reading “Keep Out, Claudia,” from the “The Baby-Sitter’s Club” book series. The story is about a client who did not want Claudia Kishi, a Japanese American member of the club, to babysit her kids. After some investigation, Kishi and her friends discover that the family, which also rejected another non-white babysitter, is racist.

The impact of the story on Korean American Yu, who grew up in Northern California, was lasting. It was one of the rare times he remembers reading about everyday racism as a kid.

More than two decades later, Yu is paying homage to the series’ lone Asian American main character by re-creating book covers about Claudia Kishi. He says the new covers paint a more realistic picture of what life must have been like growing up as one of the few immigrant kids in a mostly white town.

The popular young adult book series by Ann. M. Martin was released in the 1980s and 1990s and was about a group of friends ages 11 to 13 who ran a babysitting service in a fictional town in suburban Connecticut.

“I just kept thinking about all the microaggressions Claudia would have faced being Asian in this town,” says Yu, who runs the blog Angry Asian Man.

[[{"fid":"186046","view_mode":"default","type":"media","attributes":{"height":415,"width":900,"alt":"Three book covers.","class":"media-element file-default"},"link_text":null}]]

Yu's readers collectively lamented that there weren't many characters like artistic and fashionable Kishi during their youths. But more than that, the mock covers also illustrate how young adult books need to dive deeper into themes like race and identity.

Yu’s alternate titles covered a range of situations from everyday pet peeves — “Claudia’s Big Party” turned to "Claudia Thought She Told Everyone to Take Off their Fucking Shoes" — to more sinister situations. “Claudia and the Bad Joke,” which shows her at the hospital with a broken leg, became “Claudia Suspects It Was Racially Motivated.”

“Some people were like, ‘Is this a real book?’” says Yu. “But I did it for the fans who would get the joke.”

[[{“fid”:”186117″,”view_mode”:”default”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”attributes”:{“height”:783,”width”:615,”alt”:”A screenshot of a tweet that reads: "These remixed #Babysittersclub book covers gives me life Thanks, @angryasianman for articulating what I couldn't as a young Asian girl…"”,”class”:”media-element file-default”}}]]

Reera Yoo, who co-hosts the Asian American book club podcast Books and Boba, says that today, there are more young adult books that directly address contemporary race relations and represent the coming-of-age, immigrant experience in America.

The 2017 New York Times best-selling novel "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas is about an African American teenager who sees a police officer shoot her unarmed best friend. Samira Ahmed’s just-released debut novel “Love, Hate and Other Filters” is about a Muslim girl whose family becomes a target of Islamophobia after an attempted terrorist attack in her hometown. And C.B. Lee’s 2016 “Not Your Sidekick” is a superhero romance series that follows a Vietnamese and Chinese heroine. These are just a few examples of books published in the last two years.

Yoo points to a scene in “Not Your Sidekick” where Captain Orion, the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Commander of the League of Heroes, is talking about the protagonist Jess’ Southeast Asian refugee superhero parents. After mimicking an Asian accent to imitate Jess’ mother, Orion says she’s appalled that Southeast Asian refugees even applied to the League of Heroes and that they should be grateful they were accepted.

“It reminded me of how often people in marginalized groups are told they should be happy to just have a seat at the table,” says Yoo. “That they're lucky and shouldn't ask for more even when they deserve it.”

When Ahmed, author of “Love, Hate and Other Filters,” was a kid, her family was the first Indian Muslim family to move to Batavia, Illinois. She remembers an incident around the time of the Iran hostage crisis that began in 1979. Her family was stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic next to a car with a couple of young, white men inside.

She said one of men rolled down his window, pointed to her, and said “Go home, you goddamn fucking Iranian,” before laughing and rolling his window back up.

“It’s so crystallized in my mind, because I was in second grade, so I had never heard language like that, let alone directed at me,” she says. “At the time, I didn’t have anyone that I could talk to about similar experiences. I didn’t have literature that I could access to help me process this.”

The only book she remembers reading as a kid that featured a person of color was Scott O’Dell’s “Island of the Blue Dolphins.”

“Since then, I’ve read that some people have concerns about its representation of a Native American girl, but back in third or fourth grade, something about the book really resonated with me,” she says. “I felt like this girl did. It felt like a metaphor, that she was left alone on an island and had to learn how to survive.”

Most of “Love, Hate and Other Filters” details Maya Aziz as a regular American high school girl who is busy navigating boy problems (a love triangle between a charming Indian boy she meets at a wedding and her technically unavailable classmate she’d had a crush on since childhood) and figuring out how to tell her disapproving immigrant parents that she wants to go to New York University to become a filmmaker.

However, in between the chapters of Aziz's story are short one-page-long descriptions of a young, angry man who seems to be planning an attack. Inspired by the structure of “The Grapes of Wrath,” this subplot appears to be separate from Aziz's world, yet foreshadows a looming tragedy that will ultimately impact her life.

“I wanted to capture the everydayness of her life and then show how everyday life can be shattered by an act that really has nothing to do with her,” she says. “Unfortunately, so many kids experience that.”

“There’s also something insidious about the quiet racism,” she says. “You feel a tension walking down the street, these tentacles of prejudice spread, they impact your day-to-day life, and it’s a burden that you cannot feel or understand unless you’ve experienced it.”

A former high school English teacher, Ahmed points out that many characters of color in American literature taught to young people in schools have been written by white authors, such as Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Just over 10 percent of books for children in the US are by people of color and over 20 percent are about people of color, according to 2016 statistics from the library collection at the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin.

Also: A survey of who works in the book industry gives us a clue about why it's not diverse

But Ahmed hopes that having more books like “Love, Hate and Other Filters” can help young readers today — many of whom were not even alive when the 9/11 terrorist attacks happened — empathize with communities that are still affected by racism and hate. That’s not to discourage authors from writing characters of ethnicities that are not their own, says Ahmed. Her next book is about a biracial Indian and French girl who uncovers a literary mystery with a man who is a descendent of writer Alexandre Dumas.

“I think people should write what they want,” she says. “But do your homework and ask yourself the difficult and uncomfortable questions. Are you representing this character in a way that’s real, or is this character there just to be a learning tool for your white character or reader or yourself?”

In the end, Ahmed says, it’s especially important to create complex and nuanced characters of color for young adult readers — especially now, when messages of hatred and prejudice often dominate the news.

“For some kids, it can make them feel not alone,” she says. “For others, [they] can look through a window into someone else's experience to feel sense of empathy.”

So for everyone who thought or wished Yu's "Babysitter's Club" covers were real, there may be some comfort in knowing that a new generation of writers are making sure these stories of frustration, discrimination and survival are told to young readers.