St. Shmuni Church in Bartella, Iraq, shows damage sustained while the town was under ISIS control for two years.

Ibrahim* peers through the steel gate of the St. Shmuni Church in Bartella, Iraq, into the dark and broken interior.

This used to be his favorite place. He spent countless hours here growing up, helping the priest prepare for his sermons and doing odd jobs.

Now, the pews where he used to sit are strewn about the room, the books are burned and the door is padlocked.

“I always came here before anyone else. When I came in the morning everything was dark. I was alone. I would sit and pray,” he says.

Things have changed since then.

“I don't see this as a holy place anymore,” he says, apparently eager to move on. “I’m totally different now.”

It has been one year since ISIS was kicked out of this Christian town, following a two-year occupation. But the damage the group left behind — both physical and otherwise — has not yet been repaired.

Most of the town’s residents were able to escape before the ISIS fighters arrived in the town. Ibrahim, now 17, and his elderly mother, Nour, did not. They were held as prisoners in the self-declared caliphate for two years.

Immediately after his release last year, Ibrahim said his Christian faith had got him through the ordeal. He had even hidden a small wooden cross — which he feared would be taken by the Islamist extremists if they found it — and swore to return to the hiding place to collect it later.

But he did not return there. His experience living under ISIS changed him in a way he could never have foreseen. After holding on to his faith so tightly in the face of repeated attacks by the zealots holding him, he let it go.

ISIS turned him into an atheist.

Bartella is still in the very early stages of recovery. A dry scrub of land just outside Ibrahim’s home is littered with twisted metal and burned out cars. It’s a sight repeated throughout the town — a result of the US airstrikes that forced ISIS out. Many of the houses are destroyed or pockmarked with bullet holes.

The town is mostly quiet, but little pockets of activity speak to the cleanup underway. On the main street, circular saws grind against metal and burning sparks fly from the curb.

Ibrahim has been back in his hometown for just a few weeks now, but this is the first time he is really venturing out. He sees a restaurant that wasn’t open the last time he was here, before ISIS came along

“I remember walking down here when ISIS came and there was no one here. Only the sound of dogs,” he says.

When ISIS fighters captured Mosul and the surrounding region, they offered Christians a choice: Convert to Islam or pay a tax. Anyone who refused these options, they announced, “will have nothing but the sword.”

The people of Bartella fled in the face of the ISIS advance. When the militants arrived, they immediately set about smashing the churches and everything inside them. Ibrahim was caught when he asked one of them why he was demolishing a cross.

During Ibrahim’s captivity, he and his mother were forced to convert to Islam. They were beaten regularly and tormented by ISIS fighters.

He was only 14 at the time, and spent most of his days on his computer, bored out of his mind. These were his formative years, yet he was isolated from the world, and had no one his own age to talk to.

“They would take me from the house and take me to a prison. They would sometimes keep me there for three days. Every time, they would give me 25 lashes, shave my head and then release me,” he says.

In Bartella, nearly a year after his escape, Ibrahim seems much older. It’s as though he is making up for lost time. He has grown a smattering of facial hair and learned some English.

The brutality he witnessed under ISIS stirred something inside of him. At first, his anger was directed toward the ideology being forced upon him by his captors. But it later grew into a deeper examination of his own faith.

"After they went, I dropped all religion, all the way. I took it out of my mind,” Ibrahim says.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” he says. “It doesn't make sense. I have read both the Quran and the Bible. I read a lot. How can I believe something written hundreds of years ago? If someone told me 10 years ago you can speak from here to US, I would say it’s magic. Now you can speak all over the world.”

Ibrahim didn’t get to this point alone. After being starved stimulation during his captivity, he has since become a vociferous reader. His battered old laptop serves as his connection to the outside world, allowing him access the same ideas as any other teenager.

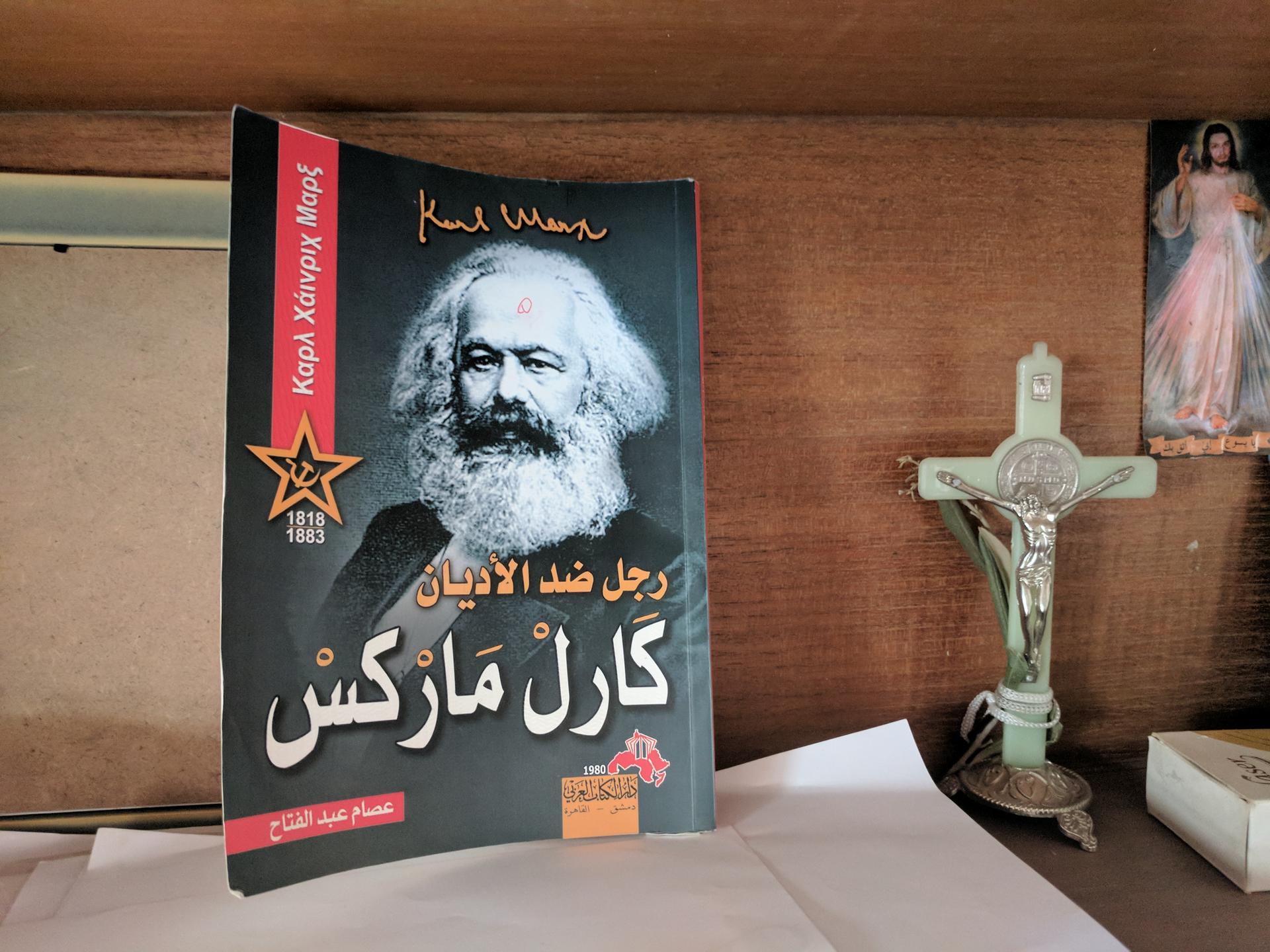

“This is Richard,” he says, opening up a video of British biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins. He has many more like it — most of them downloaded from atheist groups on Facebook. He walks over to the bookshelf and begins pulling books down. There’s Dawkins again, Charles Darwin, Karl Marx. It is as if the books had been carefully selected so as to most anger his former tormentors. He even has pictures of them all on his wall.

“I learned a lot of things from these books,” he says.

“There were a lot of questions in my mind about Christianity already. I started to question it before ISIS. After ISIS I went to research more. I discovered what religion was really about.”

Iraq is a deeply religious country where atheism is rare. The country has seen secular rulers before, but the vast majority are adherents of Islam.

Some 97 percent of the country is Muslim, according to the US State Department. The rest are Christians, Yazidis, Mandaeans and a small number of Jews.

Atheists don’t figure in these estimates, but there are indications that their number is growing — and that religious violence may be playing a role. As early as 2008, before ISIS came along, young Iraqis were showing signs of fatigue with religious teaching as a result of extremism.

Nonetheless, Ibrahim has found it difficult to talk about it with his friends.

“I feel that I have this information that my friends don’t. I feel like I can’t talk to them about it and it makes me avoid them,” he says.

In fact, he feels like a stranger in his own country now. He and his mother are trying to emigrate to Canada.

“There is not the ideology of extremism there. Here religion rules everything,” he says.

And he has a new purpose in life. He wants to be a scientist.

Richard Hall reported from Bartella, Iraq.

*The names of the people in this article have been changed to protect their identities.