Here’s how Trump’s crackdown on ‘chain migration’ will affect migrant families

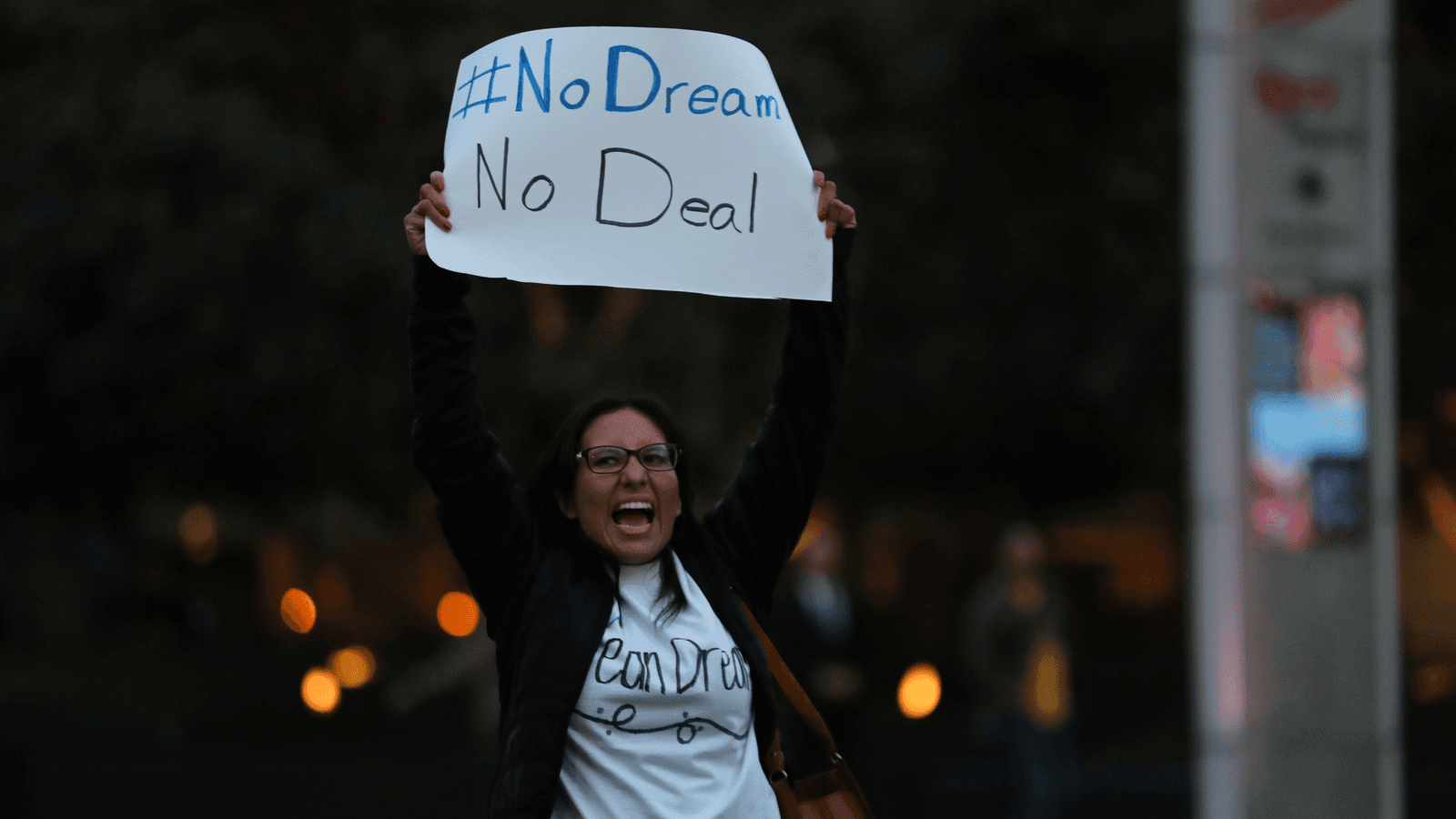

A small group of demonstrators block traffic to demand action by the federal government on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in downtown San Diego, California, Dec. 4, 2017.

Congressional leaders met Wednesday with White House officials to explore the possibility of a legislative solution that would give lasting legal status to people currently benefiting from DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Both Republicans and Democrats have expressed a desire to bring DACA recipients — typically, undocumented migrants who were brought to the US as children, then grew up here — into the fold. But with a president who rode into office using anti-immigrant rhetoric, it’s unclear what kind of concessions might be made.

Trump has repeatedly said that any DACA legislation must be tied to a border wall with Mexico. But in recent months, he’s ratcheted up his rhetoric on so-called "chain migration," or family-based immigration.

"Ending chain migration, and also ending the visa lottery, will allow us to have common sense immigration rules, that promote assimilation and wage growth," the president said in a Dec. 16 White House address. "It also promotes, most importantly, safety. It will help Americans both old and new to thrive, flourish and prosper."

Dara Lind, a senior reporter for Vox, says ending family-based immigration could have far-reaching consequences for the US.

“[It’s] the way that a little over half of people who come to settle in the US come — because they have a relative who’s a US citizen or in some cases a green card holder,” she says. “The thing is, a lot of kinds of family-based immigration don’t really create chains in the way you think of them.”

According to Lind, if a person is granted US citizenship or a green card, they cannot continually bring over family members.

“The most common types are just bringing over your spouse, which you can only bring one spouse over, or bringing over your kids, who don’t then have other relatives they can bring because they’re kids,” she says. “The more chain-like types of migration are like bringing over adult children or siblings, other people who might have families they can bring, and they’re pretty limited — they’re a lowest priority for immigration.”

An example: It can take a decade or longer for a US citizen originally from Mexico to bring over a sibling, Lind says.

“[Chain migration] is a term that, policy-wise, refers to this small slice of family-based immigration but politically has come to mean the whole thing,” she adds.

This notion is something that President Trump has continually tried to drive home.

“A single immigrant can begin a chain that can ultimately bring in dozens of increasingly distant relations,” the president said last month. “Because these individuals are admitted solely on the basis of family ties, not skill and not merit, most of this immigration is lower skilled, putting great strain on federal welfare.”

President Trump’s idea of chain migration, Lind says, represents the most extreme hypothetical scenario. In reality, she says most people who rely on family-based immigration only wind up bringing over a few relatives to the United States, adding that individuals who rely on social services like welfare are barred from coming to the country.

Despite the facts, a deep fear of “chain migration” has become a key focal point for those on the right. But how did we get here?

“For a generation, Republicans rhetorically said, ‘We love legal immigrants, we just don’t like illegal ones or unauthorized ones.’ For a lot of conservatives, however, that wasn’t really their problem with immigration,” she says. “Their problem with immigration was that they didn’t want the cultural mix of America to change, they thought that America had a traditional culture and traditional values, and they didn’t want people who didn’t respect that culture and values to start dominating the American population.”

While President Trump wants a merit-based immigration system that favors high-skilled workers, Lind says such systems are not always ideal. She points to Australia and Canada, which have had difficulty getting the long-term benefits of hosting immigrant workers, many of whom are reluctant to put down permanent roots in their communities without their family members.

Though he claimed on the campaign trail that Mexico would pay for it, President Trump is trying to secure funding for his border wall. Lind speculates that the president will give Democrats a DACA deal — if family-based migration is cut and at least some funding for the wall is secured.

“He’s asking for a cut in legal immigration to the US going forward by as much 50 percent in exchange for legalization of the 700,000 of the 11 million unauthorized immigrants currently living in the US,” she says “That doesn’t seem like a super-even deal. The continued insistence on ending chain migration in the White House seems like a signal that they’re less interested in getting to a deal on DACA than they are in treating their entire immigration agenda, which is a radical remaking of American immigration policy, as this obviously done deal that Democrats must ultimately fold on.”

A version of this story originally appeared on The Takeaway.