Farofa is a crunchy garnish, made from cassava root flour fried with some combination of meat such as bacon, fruit such as raisins, or other flavors like bell peppers and olives.

When I began cooking holiday meals in Brazil, guests appeared with a dish I did not expect — a reminder that the Christmas dinner menu is just as shaped by history and politics as everything else here.

Brazilian Christmas dinner usually stars turkey or a regional meat, which varies from beef from the cattle grazing south to fish from the northern waters of the Amazon. Frozen turkey is hard to find in supermarkets at other times of the year, which I discovered while searching for one in November.

Related: Is Christmas demon Krampus losing his edge?

We located a turkey in a market across toss and an American friend and I proposed a Thanksgiving potluck.

This is a scheme so foreign to the Brazilian hosting style that it goes by the nickname festaamericana — American party. But our Brazilian friends agreed to participate and several arrived at my Rio apartment bearing the same turkey topping, a dish called farofa.

It is a crunchy garnish, made from flour of a native Brazilian cassava root fried with some combination of meat such as bacon, fruit such as raisins, or other flavors, like bell peppers and olives.

“The sky is the limit” for farofa ingredients, said chef Natacha Fink — and chefs and home cooks nationwide tout different farofa recipes depending on whether they’d like to add a taste that is savory, sweet, or in-between to their roasts.

It was the native Brazilians — “our ancient grandpas” — who first developed the technique of drying and grinding a cassava root in order to make flour, said chef and culinary researcher Paulo Machado.

Cassava flour has a mild, nutty taste. It was such a staple of the indigenous Brazilian diet that it earned the nickname “bread of the tropics.” Machado said that farofa was then invented by using cassava flour to create a variation on the Portuguese breadcrumb-based topping migas.

Brazilian farofa is popular year-round, but Christmas inspires special variations. Fink makes one with walnuts and almonds; another common Christmas farofa features raisins made from in-season grapes from Brazil’s December summer.

But farofa was not always such a celebrated accompaniment to the Christmas turkey. In fact, for years Brazilian poultry producers ran ads promoting a North American or British-style Christmas turkey dinner.

Historian João Máximo da Silva explained that in the mid-20th century, after Brazil participated in World War II alongside the allies, American television and cultural imagery flooded the country.

“All of this accelerates into the Cold War,” Silva said, “and includes ideas surrounding food.”

The frozen Christmas turkey was first mass-marketed in Brazil during the 1970s, when the country was ruled by a US-aligned military dictatorship.

Today, Natacha Fink says the culinary world is moving away from the idea that “what comes from abroad is better.” She said the past 15 to 20 years have brought a new interest in researching and cooking foods with native Brazilian ingredients.

Related: Britain’s strange addiction to a medieval Christmas treat

João Máximo da Silva now coordinates a São Paulo university program about Brazilian gastronomy, and Paulo Machado has returned from years of overseas culinary study to lead “Brazilian food safaris” in far reaches of the country. Farofa has assumed a place of honor not only at Christmas dinner but also at restaurants like Fink’s Espírito Santa, recognized as one of the best in Rio.

There, Fink has served Amazonian fish farofa as a standalone dish and makes farofa sides with banana, coconut and palm oil.

“Today,” she said, “farofa is gourmet.”

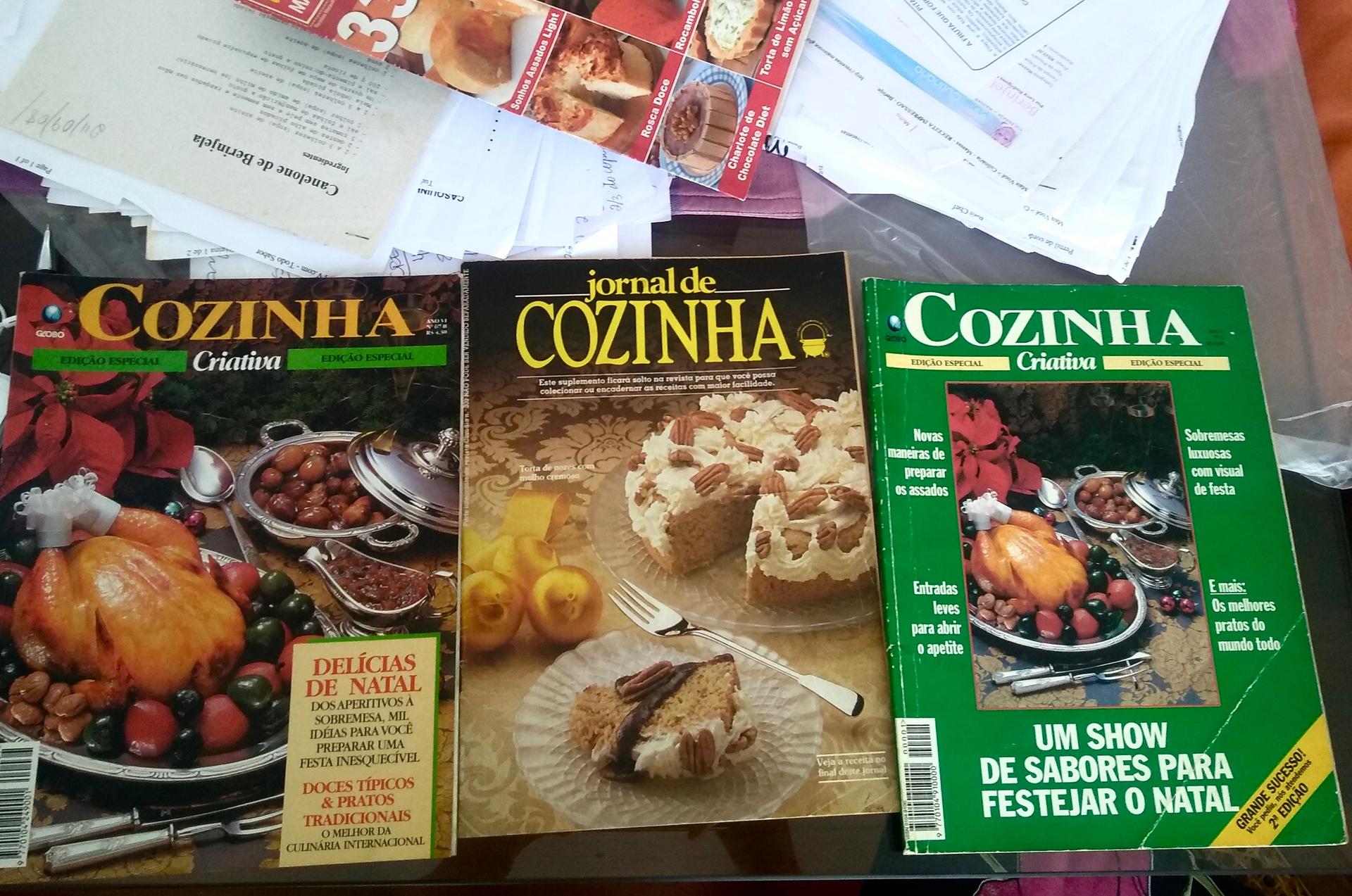

The curious home cook can find dozens of recipes by Googling “Christmas farofa.” One Brazilian friend told me she waits all year for her family’s Christmas farofa, made by a recipe passed down from her aunt to her mother, who sifted through stacks of cookbooks in order to share it with me.

“I used to think it was not a big deal,” said her mother, art teacher Magaly Henriques, chuckling. “But the kids have now made it clear that it is one of the most important parts of Christmas.”

Turning serious, she added, “Oh, it’s very good.” The farofa combines onions, garlic, bell peppers and parmesan cheese to complement Christmas meats.

“And it’s not just about the flavor,” Henriques said, with a now-familiar comment about the topping. “It’s about the texture. It’s a whole experience.”

Natacha Fink’s Basic Farofa

For a basic farofa with cassava flour, sauté onions and any meats together first, then add the rest of seasoning together with the flour.

2 cups cassava flour

1 diced yellow onion

2 teaspoons olive oil

2 teaspoons herbs such as parsley

Salt and pepper to taste.

1. Sauté onions in oil until they are golden.

2. Slowly mix in cassava flour, adding salt, pepper, and herbs to taste. The cassava flour will darken — either from white to gold or yellow to dark yellow — but should not smell burnt.

Henriques Family Christmas Farofa

This is an adaptation of a farofa said to have been invented by Brazilians who were living abroad and could not find cassava flour. It uses crushed cream crackers as a substitute.

250 g cream cracker

1 can of corn

1/2 cup raisins

1/2 cup chopped green olives

4 eggs, hard-boiled and chopped

2 teaspoons of butter

2 teaspoons of olive oil

1 diced yellow onion

1 clove of garlic

1 red bell pepper

1 yellow bell pepper

4 teaspoons of parsley

1 cup of grated parmesan cheese.

1. Crush the cream crackers.

2. In a deep pan on the oven, brown the onions in the oil and butter.

3. Add all of the remaining seasoning, including bell peppers, olives, and raisins.

4. Lower heat and slowly fold in the cream cracker until it is well-mixed with seasoning.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!