Free after five decades on death row, a Japanese man may be forced to return

Iwao Hakamada, thought to be the world’s longest-serving death row inmate, at his sister’s house where he now lives, waiting for the Supreme Court to decide whether he’ll be sent back to death row.

Every day, in any weather, 82-year-old Iwao Hakamada walks around the small Japanese city of Hamamatsu for up to six hours. A volunteer follows a few steps behind to be sure he doesn’t get hurt and can find his way home.

Hakamada suffers from a mental condition diagnosed as “prison psychosis,” the result of spending nearly five decades on death row — thought to be the world record — for a quadruple murder that evidence suggests he did not commit.

In 1966, he was a 30-year-old former professional boxer working at a miso factory, when the manager, along with his wife and two children, were found stabbed to death in their home, which was then set on fire. Hakamada lived on-site and was the only suspect. No one could corroborate his alibi that he’d been in his dorm room and rushed to the fire to help put it out.

Police detained him for about three weeks and according to records from the detention center, interrogated him for up to 14 hours a day. He alleged they beat him with nightsticks, pricked him with pins to keep him awake and denied him adequate food and water until finally he confessed. He later retracted the confession in court.

“It’s striking, almost stunning, how long the interrogations went. Day after day after day, before finally on day 20, Hakamada confessed,” said David Johnson, professor of sociology and an expert on the Japanese justice system at the University of Hawaii. He said false confessions are a major source of wrongful convictions in Japan.

Overall, Japan’s conviction rate is above 99 percent, meaning almost every criminal case that goes to trial ends in conviction. In part, that’s because prosecutors only bring cases they think they can win, said Johnson, and many of those cases are built on confessions.

Hakamada was imprisoned for 48 years — 30 of them in solitary confinement. Every morning, he awoke at 7 a.m. to find out whether that would be the day he would die by hanging. Japan does not give prisoners advance warning of their executions.

The US and Japan are the only G7 countries that still have capital punishment. The UNHRC has urged Japan to consider abolishing it, pointing to the large number of crimes that can carry a death sentence, the lack of pardons and the execution of elderly and mentally ill convicts.

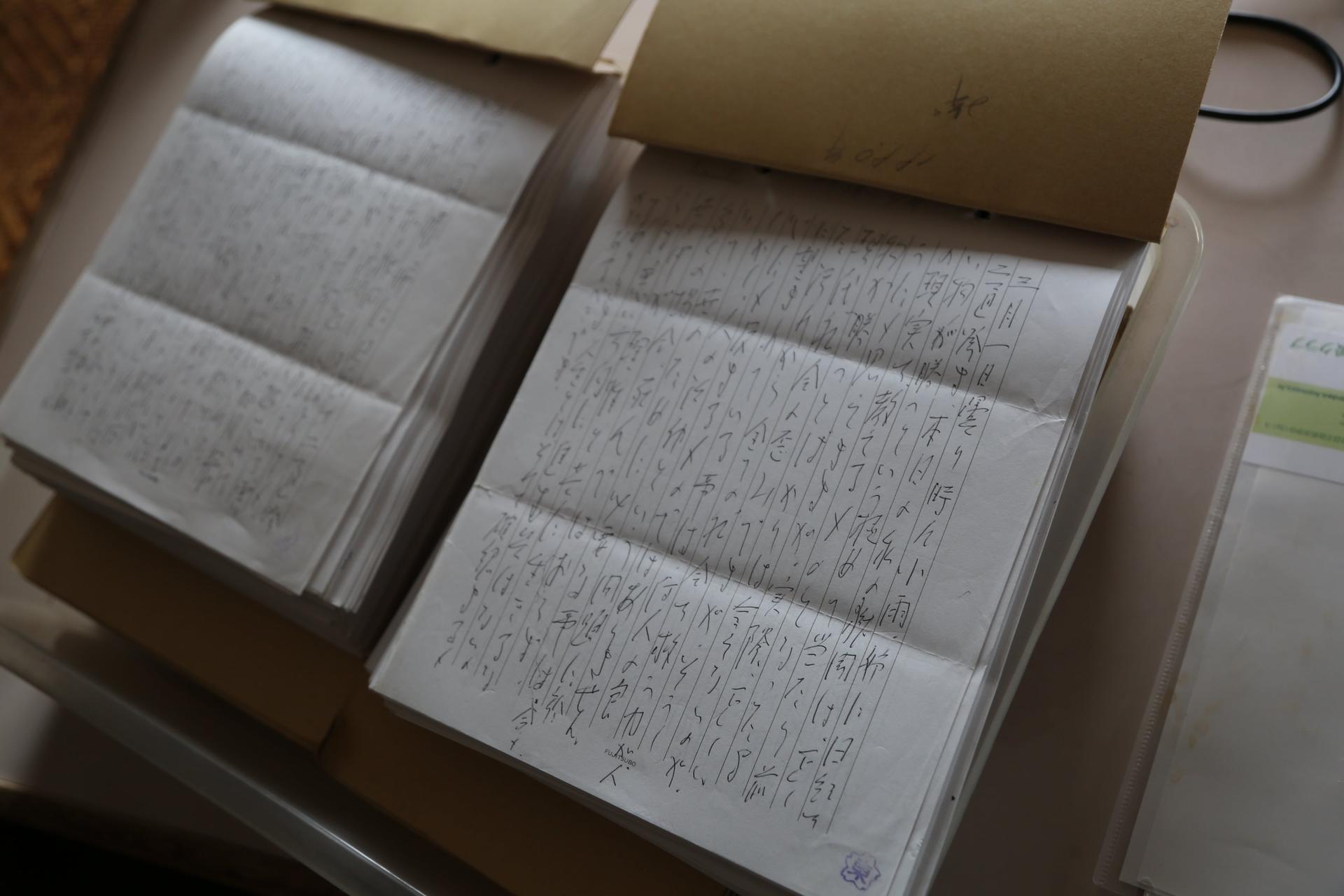

For Hakamada, decades of living in existential limbo took a toll on his mental health. His decline can be charted in the letters he wrote his family that his sister Hideko keeps in a box at her house, where he now lives.

The earliest letters from the 1960s, are written in neat rows of Japanese characters and filled with hope.

“The report about the first trial showed evidence was faked and the court misinterpreted the facts, so I truly believe there will be a retrial and I’ll be cleared,” one reads. “I’m doing OK so don’t worry.”

Then in 1980, after 12 years of appeals, the Supreme Court upheld his death sentence. Hideko says that was a turning point for her brother.

“Not long after that, he told me the man in the cell next to his had been taken away and on the way out, he said, ‘so long, hope you stay well,’ then never came back. And that was when the death penalty became real to him, and it was very scary.”

His letters from that time show his mind starting to unravel; he writes about devils tormenting him in the shower.

“I could tell he was getting seriously mentally ill,” said Hideko. “So I visited every month, but sometimes he refused to see me. I kept going though, to tell him his family hadn’t abandoned him.”

Then nearly 50 years after he was first imprisoned, Hideko filed for a retrial based on new DNA evidence: Hakamada’s lawyers said his blood did not match blood from the crime scene.

A district court granted the retrial in 2014, writing it was “possible that key evidence had been fabricated by investigators” and that it was “unjust to detain him because of the clear possibility he was innocent.” Hakamada was released to his sister.

“I remember that day so clearly. I was 81 and I smiled for the first time since I was 33,” Hideko said. “It was like I became myself again.”

It was also a joyful day for a judge in the original case. Norimichi Kumamoto was chief of the three-judge tribunal that heard Hakamada’s case in 1968. He later said he believed Hakamada was innocent but couldn’t convince the other two judges. Still, as head of the panel, he had to write the death sentence. He said the look on Hakamada’s face when he heard the sentence haunted him. So he quit the bench a few months later, became estranged from his family and wandered the country.

When Hakamada was released, Kumamoto met him to apologize. The judge was so frail he couldn’t speak but Hideko still thinks the visit meant something to her brother.

That is not the end of the story though. Because in Japan, prosecutors can appeal rulings and this past June, the Tokyo High Court overturned the decision that set Hakamada free.

The case now goes to the Supreme Court. If Hakamada loses his appeal, he could be sent back to death row.

“Obviously it’s a tragedy for him if he goes back to death row after being released,” said attorney Kiyomi Tsunogae, a member of Hakamada’s defense team. “But it’s also a tragedy for this country. I don’t know any other nation that has done this. They don’t want to admit that they fabricated the evidence and made a mistake 50 years ago.”

Tsunoga said judges are political appointees and can sometimes be more concerned with satisfying the government than administering justice.

Still, there were concerns about how the DNA evidence was handled — the expert witness failed to keep records, for example. Despite that, Johnson at the University of Hawaii said he thinks the court made the wrong decision and Hakamada should have been granted a retrial.

“I believe he’s actually innocent but I can’t be 100 percent sure of it,” said Johnson.

Johnson said it’s possible Hakamada could be sent back to death row but then granted executive clemency, and that it could actually increase public support for the death penalty because the government would be seen as acting mercifully.

For now, the court has allowed Hakamada to remain free on bail at his sister’s house and a community group formed to help care for him. Every day, a volunteer named Ino drives over an hour from her house to cook lunch and make sure there is always someone to accompany him on his walks.

Hakamada himself doesn’t seem to fully grasp his situation but remains upbeat.

“I feel good, I’m healthy,“ he said. “The world is developing and becoming a good world — the companies tell you, you can make a lot of money and the authorities don’t punish you anymore.”

His sister just listens and doesn’t push him to talk about his time in prison.

“Even death row inmates, they’re not animals. They’re still human and they should be treated with humanity — so I do think Japan should get rid of the death penalty,” she said. “As for my brother, of course, I’d like the Supreme Court to say he’s innocent but if he gets to stay out of prison, that’s better than nothing.”