In South Korea’s war panic economy, sales thrive on nuclear angst

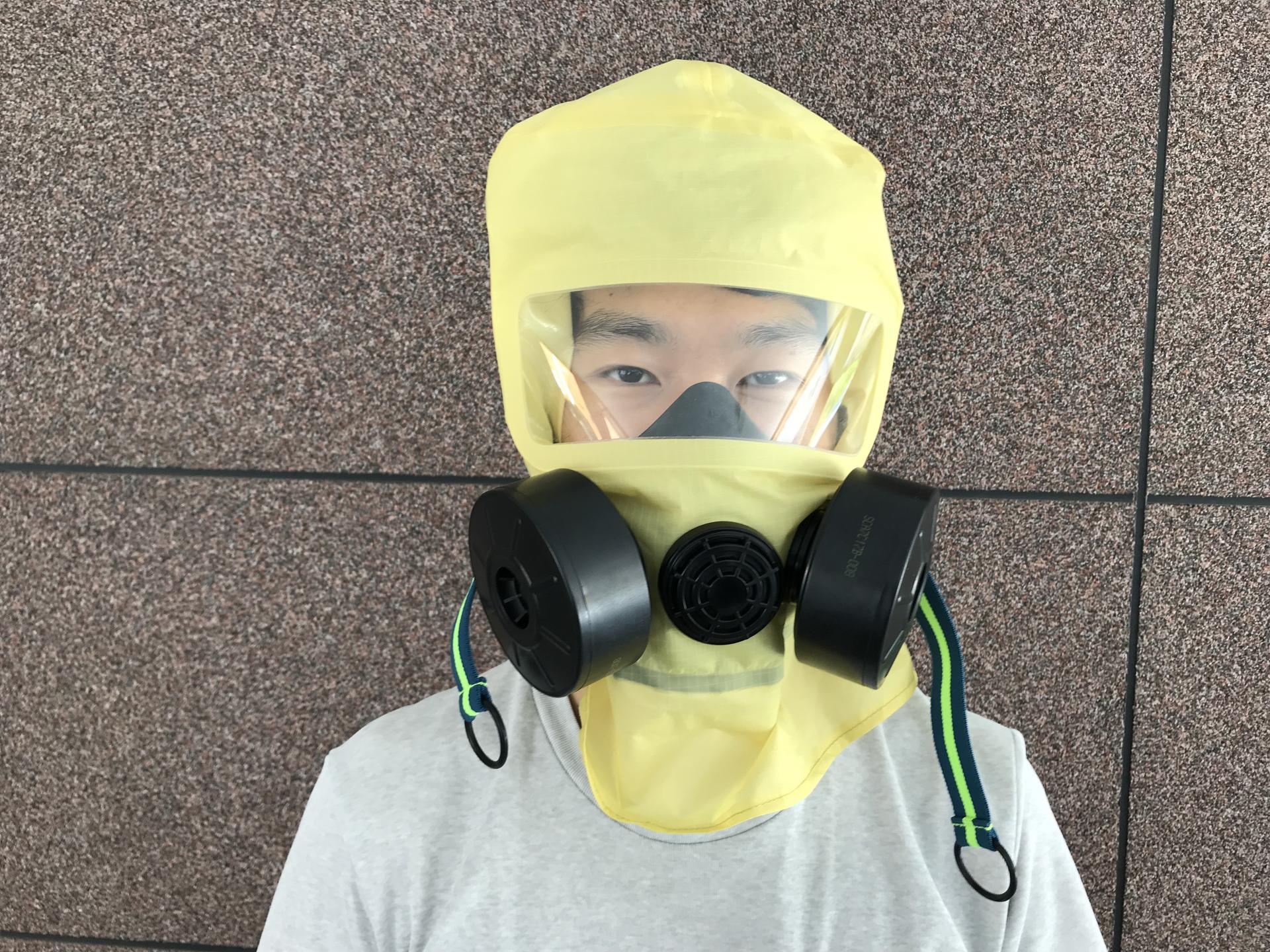

South Korean teenagers near Seoul wear gas masks for a military drill to prepare for radiological attacks.

Seoul is renowned for its stoicism in the face of potential war. At least that’s what we’re often told, that the majority of people in this city of 25 million can wake up to North Korean threats about immolation in a nuclear “sea of fire,” shrug and just go to work.

Even when Pyongyang was detonating nukes last fall — and US President Donald Trump spoke of bringing “fire and fury” to their peninsula — polls suggested that roughly six in 10 South Koreans believed there was “no possibility” of war. (Even Americans living an entire ocean away appear more panicky over North Korean nukes than that.)

But what about those in South Korea who can’t shake an impending sense of doom? For that anxious minority, there is a marketplace offering to aid in their survival should North Korea ever unsheathe its self-proclaimed “nuclear sword of justice.”

Call it the war panic economy: a small industry selling all the stuff you might want on doomsday. Think gas masks, hazmat suits and emergency rations. Or, for the upper classes, your own personal bunker.

“We have government shelters all over South Korea. But we all know they’re not completely safe,” says Go Wan-hyeok, a Seoul-based entrepreneur in his 50s. He is referring to the nation’s 3,000-plus civil defense shelters, many of them located in train stations or under malls.

“They’re not as sturdy as the real bomb shelters — the ones on our army bases or run by the Americans,” Go says. “So I wondered: Why shouldn’t civilians have access to their own top-notch bunkers?”

Interact:What would you do if you ran a country with nuclear weapons and were asked to use them?

In September, Go opened up a showroom selling customizable, nuclear radiation-proof personal bunkers. So much for stoicism; Go wanted to target the roughly 40 percent of South Koreans who do anticipate North Korean aggression.

His timing was ideal. Trump had recently dropped his line about fire and fury. The US president followed that with a fusillade of tweets about his “nuclear button.” Go’s shop was soon fielding dozens of calls each day.

“For the most part, my customers are very conservative,” Go says. “They’re rich, basically. Because they can (afford to) build a bunker under their houses.”

His priciest bunker runs about $37,000. That buys a roughly 600-square-foot sanctum, complete with four beds, a sink trickling out purified water, an electrical system powered by a hand crank and an air purification system that can filter out radiation.

Imagine a small studio apartment with rounded steel walls, as in a submarine, with an entrance hatch that’s heavy as a bank-vault door. To make the bunker fully nuke-proof, he says, it must be buried underground and encased in cement.

“My clientele tend to be people in their 60s or older who might have memories of the war,” he says. “Often they want to provide bunkers to their sons or daughters.”

Those old enough to recall the aftermath of the Korean War can be forgiven for shivering at any mention of a redux. Between 1950 to 1953, parts on the peninsula were turned to veritable seas of fire, largely thanks to more than half a million American bombs.

As Curtis LeMay, the US Air Force general overseeing the aerial campaign, put it:

“Over a period of three years, we killed off — what? — 20 percent of the population of Korea as direct casualties of war or from starvation and exposure.”

That these horrors exist within living memory might explain why some elderly Koreans feel especially jumpy over Pyongyang’s bombast — or aggressive tweets sent from the White House. Go has noticed that calls have spiked when either side makes threats.

But there is a flip side to this war panic economy. When fear runs hot, it thrives. But when peaceful vibes pervade, it practically collapses.

Images of Trump and Kim Jong-un shaking hands have been great for lifting the blanket of dread over South Korea. But for any business that relies on war angst, peace is poison. Go has sold 10 bunkers since he opened, but once Trump and Kim became friendly, interest plummeted.

Not that this is altogether bad, Go says. “That handshake is a very, very good thing. A peace mood has come to Korea.” He has since taken to emphasizing the merits of owning a bunker during a Fukushima-style nuclear meltdown or a tsunami.

He’s been quoted in a UK tabloid, The Mirror, as saying that he is “wishing (Kim Jong-un) presses the button and shoots the bomb” just to drum up his sales. Go says this quote is totally fabricated and that he does not, in fact, long for the nuking of his own country, which would make it tricky to run any business whatsoever — even one selling bunkers.

It is indeed unfair to assume that every entrepreneur in the war panic economy is cynically exploiting fear for profit. Sellers such as Lee Sang Joon, the proprietor of the online mail-order outlet Prepper Shop, are emblematic of the smaller players in this boutique market. He is a bona fide “prepper:” one so convinced that war is nigh that he or she actively plans for the worst.

Part hobbyists, part doomsayers, preppers are often keen to evangelize to the masses, shaking them by the shoulders until they realize they’re not as safe than they imagine. That conviction led Lee — a thin, bespectacled 25-year-old who studied aerospace in college — to open his shop.

Lee sells hundreds of items, all of which might prove handy in a world turned anarchic by nuclear or chemical attacks. Among his inventory: flare guns, attack batons, radiation detectors, four types of gas masks and, for the discriminating survivalist, emergency rations that taste like French Basque-style chicken stew.

Preppers in South Korea, he says, “almost always have a story. They’re people who’ve experienced some sort of disaster.”

His own disaster was lymphoma, which struck in college and receded only after a barrage of chemo treatments. That taught Lee a lesson: life can be unpredictable and cruel.

In South Korea, men and women who experience a similar epiphany, he says, will often suddenly become sensitive to the ever-present chatter of war: the routine threats of death and darkness that swirl around the media.

“We hear this all the time in Korea,” Lee says. “It’s not that the general public is naive. They too know disaster may come. They’ve just decided preparing is pointless.”

But Lee notes that there is a big exception to this status quo. Sometimes events will rile the public, such as Pyongyang testing nukes in succession or the US president bellowing about war. When that happens, Lee says, millions of Koreans start to think more like preppers overnight. All of a sudden, buying a gas mask doesn’t seem so irrational.

Last fall, after Trump’s fire-and-fury statements, Lee was hit with a deluge of orders. He would run around his stuffy little warehouse, frantically filling orders until he felt like fainting. Each new statement from North Korea or Washington, DC, seemed to bring on a new wave of calls.

Meanwhile, Lee was struggling to squelch his own feelings of alarm. He is, after all, someone who constantly frets about impending war. So when Trump and Kim finally met and shook hands, he felt immense relief — even as his sales plummeted by roughly 90 percent.

“I’m so much happier now,” he says. “We have hope for a peace era.”

“Imagine if war really happened. They might bomb my city first because it’s a military target.” (Lee lives in Changwon, an industrial city home to a naval base and factories supplying materiel to the military.) “Think about all the people who don’t prepare, including my friends and family, who would be in danger. Forget this shop. What good would extra money bring in such a terrible situation?”

When I met Lee in his warehouse, the young proprietor was busy taping up boxes, sorting through inventory and preparing to close down his business. Personally, he’s not at all convinced North Korea is ready to permanently forsake its nukes. But he’s pleased that the threats have subsided. As, it seems, is the public. Selling gas masks during peace negotiations is as hard as selling snowshoes in June.

Lee may head back to university, perhaps to study disaster preparation at a professional level. But in his free time, he’ll remain devoted to his prime avocation: amassing gear and perfecting his survival plan should the bombs fall.

“I can imagine how it would look,” Lee tells me. “People outside would first see a white light — one that would blind their eyes and scald their skin. Seconds later, the shock wave would come: shattering windows, causing fire, smoke and chaos. It would be cruel and brutal.”

Like most South Koreans, Lee isn’t wealthy enough to buy a private bunker. “But I know where exactly where I’d run,” he says. “To my apartment’s basement. I can get there in five minutes.”

Editor’s note: We’ve partnered with a video game company to let our readers put themselves in the shoes of someone charged with deciding whether to use nuclear weapons. Try the game for yourself at nucleardecisions.org.

Essential reporting for this story was provided by Sona Jo, a filmmaker based in Seoul.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?