How a small church in Massachusetts became a destination for LGBTQ asylum-seekers from all over the world

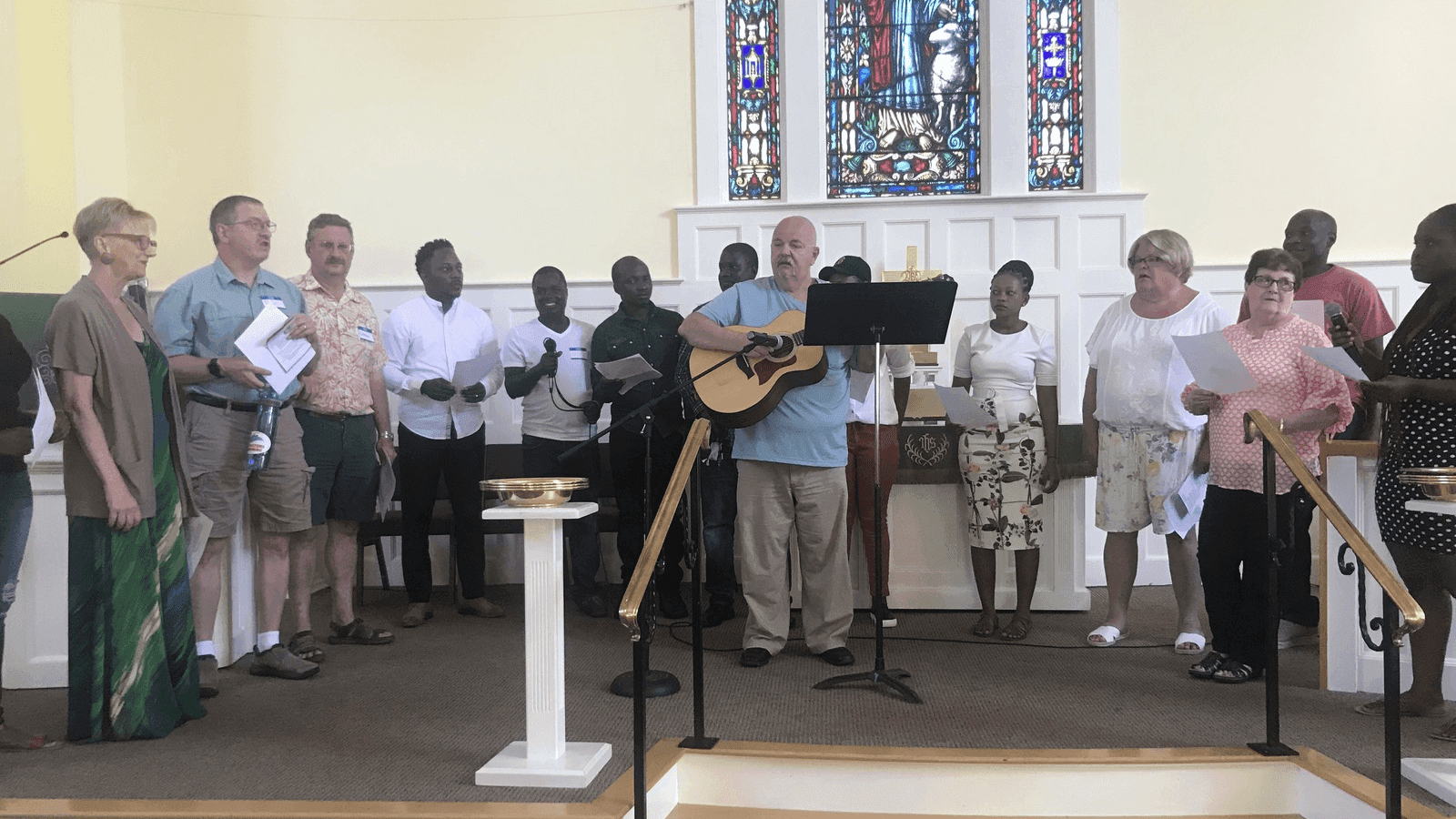

Rev. Judith Hanlon (far left) leads choir practice before mass at Hadwen Park Congregational Church.

On a quiet street in Worcester, Massachusetts, there’s a little white clapboard church with a steeple called Hadwen Park Congregational Church. Over the past decade, this classic-looking, century-old New England church has become a destination for migrants who were persecuted for their gender or sexual orientation and had to flee their homes. Some find the church online: If you google words like “asylum-seeker,” “LGBT” and “looking for help,” this church comes up. Others hear about it through word of mouth.

Thomas, a documentary filmmaker from Uganda, arrived here in December. He didn’t want to use his real name because he’s worried about the safety of his family members back in Uganda. Thomas is gay, and in Uganda same same-sex relationships are illegal. Thomas made a couple of documentaries about how gay people are treated in his home country and, while filming one of them, he was arrested and outed to his community.

Violence against gay people is common in Uganda and Thomas feared for his life. He had a visa to come to the US, because he had been in the country for a screening of one of his films, and a friend told him about Hadwen Park Church, and that it could help him.

Thomas shakes a little bit when describing his journey.

“In the flight up there, you don’t know what’s going to happen,” he says, “It’s like being on a canoe in the middle of the ocean, you don’t know where the wind is going to blow you.”

But Thomas’ leap of faith worked out. When Thomas arrived at the airport, a volunteer picked him up and brought him to Hadwen Park Congregational Church. There he met the pastor, Rev. Judith Hanlon, or Pastor Judy, as everyone calls her, a woman with bright glasses and cropped hair, who hugged him. Thomas says that after a long time of feeling afraid, he finally felt safe.

Through a mostly volunteer program called the LGBT Task Force, Hadwen Park Church has helped about 150 asylum-seekers like Thomas. The program provides them with housing and a stipend while they wait for their Social Security numbers and work permits to come through, a process that can take over a year. While many asylum-seekers rely on family or friends to get through that time, LGBTQ asylum-seekers often don’t have family to turn to and feel stigmatized by their community, even in the diaspora. That’s where Hadwen Park comes in. Currently, the church is assisting 25 asylum-seekers, which costs about $25,000 dollars a month. Most of the money comes from donations from other churches. Hadwen Park also holds an annual fundraising gala.

An important aspect of the LGBT Task Force program is the monthly meetings that Rev. Judith Hanlon leads with Al Green, a deacon and the LGBT Task Force’s only full-time employee. They take place on the second Monday of every month. The point of these meetings is to help the asylum-seekers adjust to life in the United States. During one, they cover everything from how to get your lawyer to focus on your case to roommate issues since many of the asylum-seekers live together. It ends with a vocabulary lesson.

“My wifi sucks,” an asylum-seeker calls out when Deacon Green asks if there is anything else anyone would like to discuss.

“What does ‘sucks’ mean?” asks another.

Two of the men at the meeting, who didn’t want to use their names since they were worried about impacting their asylum cases, are a couple. They came to the United States from Jamaica, where they dated secretly for years because of the anti-gay violence there. That’s why the first question that Rev. Judith Hanlon asked them jarred them. She didn’t ask if they were going to get married; her question was, “Are you going to book the church anytime soon?”

The two of them did get married here, in June, and the LGBT Task Force threw them a surprise reception.

“We got down and they had all the rainbow colors,” one of them says.

“It was so pretty,” finishes the other.

Hanlon says she never intended to become an activist for LGBTQ rights specifically. She was raised in a Pentecostal church in Indiana and gay rights were not exactly on her radar. But about 10 years ago, a lawyer referred a man from Jamaica to her church who was unable to focus on filing his asylum case because he was homeless. Her congregation, which is much more progressive than the one she grew up in, found the funds to help him. After that, the program grew and morphed.

“I believe in justice. And what comes to you. What does God send to you?” she says.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?