Jailed Kurdish politician looks to upset Erdoğan’s designs for a ‘new Turkey’

A supporter of Turkey’s main pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party holds a portrait of their jailed former leader and presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtaş during a campaign event in Istanbul, Turkey, June 17, 2018.

One candidate vying to become Turkey’s next president is spending the historic election in a jail cell.

Selahattin Demirtaş, who led the Kurdish political movement to a record electoral finish just three years ago, reaches voters from behind bars with Twitter posts that poke fun at his incarceration and a virtual campaign rally staged during his weekly 10-minute phone allowance to his wife.

The former human rights lawyer has been in prison for nearly 20 months without a conviction on terrorism charges arising from fiery political speeches that targeted President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s authoritarian style of rule. Now, opinion polls uniformly show the incumbent ahead in a crowded field of six contenders for an office with immense new powers as the country transforms from a parliamentary democracy into a turbocharged presidential system.

Related: These Turks would rather leave their country than continue living under Erdoğan

But Kurds, who make up a fifth of the population of 80 million people, could still upset Erdoğan’s plans by depriving his party of a majority in a concurrent parliamentary poll.

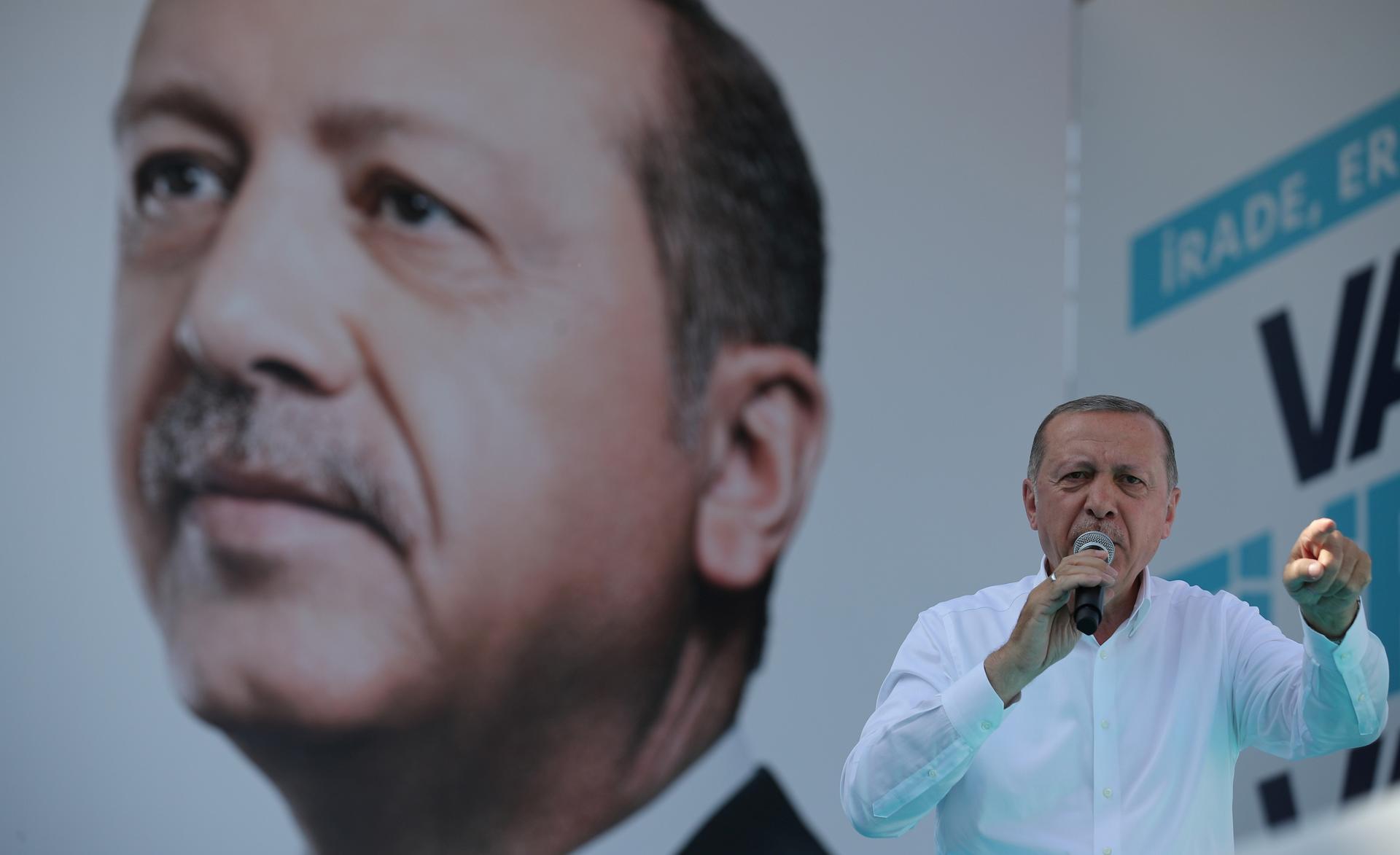

Erdoğan, 64, has dominated politics for 15 years, first as prime minister and then president since 2014, tripling the economy, driving a robust foreign policy and scrapping bans on the expression of Islam. His opponents accuse him of acting like a latter-day sultan. After a botched military coup attempt against him in July 2016, Erdoğan ordered a state of emergency and oversaw a crackdown on dissent and the press in which tens of thousands have been jailed and dozens of media outlets banned. His rivals now see a rare opening to tap voter discontent with an economic downturn and the state of emergency.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3Ddx3u1yegmSk%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

Keeping Demirtaş in jail during his quixotic bid to become head of state has cast a pall over the elections, and international observers have questioned how fair they will be under emergency rule.

“Erdoğan’s campaign would be far more difficult if I were free,” Demirtaş, 45, said in an interview submitted through his lawyers, describing his detention as “tragicomic.”

“Just think: I aspire to govern this country, and my application to be released was denied because I pose a ‘flight risk,’” he said. “This is less about punishing me than it is about seeking revenge.”

Turkey’s next president will gain vast executive powers as constitutional changes Erdoğan won in a 2017 referendum go into effect. He or she will appoint senior judges, issue decrees as law and draft budgets — the kind of authority Erdoğan insists Turkey requires to sustain rapid economic growth and confront a tumultuous Middle East. Critics say the president will have unchecked power with little oversight from parliament and the state’s few checks and balances that are still intact will be eliminated.

The “new Turkey” Erdoğan extolls at campaign rallies hinges on the head of state in control of all three branches of government.

Those plans could now be spoiled by the Kurds. About half traditionally back Erdoğan’s conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP), believing the strongman could bring peace and prosperity to their strife-torn homeland in southeast Turkey.

But many are disenchanted after the 2015 collapse of Erdoğan’s peace initiative with the armed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) unleashed the worst violence in the three-decade insurgency, killing some 3,500 people. A military campaign earlier this year to flush Syrian Kurds fighting ISIS from the Turkish border not only pitted Ankara against its NATO partner, the United States, but embittered Kurds at home.

Should they now turn to Demirtaş’ left-wing Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), they will push it across the 10 percent vote threshold parties must reach to enter parliament. If the HDP falls short, its seats will go to the AKP, the second-biggest party in Kurdish areas, clinching a majority in the 600-seat parliament. The HDP’s support hovers at 10 percent.

Related: The ‘Syrian Erdoğan‘ running in Turkey’s parliamentary elections

Erdoğan appears rattled. A surreptitiously recorded video this month purportedly shows him urging party leaders to conduct “special work” on voter registries to keep the HDP below the threshold. In public, he calls Demirtaş a “terrorist” and hinted he would like to re-introduce the death penalty as punishment for his opponent’s alleged links to the PKK.

Demirtaş, whom Erdoğan tapped to mediate with the PKK during the doomed peace process, calls those accusations “slander.”

“I have clearly stated that the HDP has absolutely no organic links with the PKK. I believe the PKK needs to lay down its arms in a process of transparent negotiations,” he said. He conceded his calls to the PKK to halt renewed clashes in 2015 proved fruitless but blames the government for “shrinking the political sphere, leaving us no space to make our voices heard.”

Demirtaş still faces an implicit boycott by the Turkish press and so has turned to social media to campaign, joking about prison-cell speeches to an audience of one, his cellmate.

Translation: Dear diary, I am about to attend the rally to complete today’s campaign work. I’m a little worried that the only participant, Abdullah, will short-circuit from overload 🙂

On Friday, he held a Twitter Q&A, responding to voters’ questions with handwritten notes that his lawyers ferried out of the high-security facility.

Tweet: “My chairman, is your faith total that if you run the country and everyone follows the orders you give, everything will suddenly be a bed of roses?”

Demirtaş’ handwritten response: “If the country were a bed of roses with orders, we would all be nightingales by now. Together we will right all of the wrongs with democracy. Greetings.”

It’s a far cry from his June 2015 campaign, when the PKK ceasefire allowed for a blossoming of civic life. The affable Demirtaş appeared on talk shows strumming a lute and fired up campaign rallies that drew supporters beyond the HDP’s Kurdish base who saw the lawmaker as a persuasive critic of Erdoğan’s drive for one-man rule.

They helped the HDP win 13 percent of the vote, depriving the AKP of single-party rule for the first time since 2002. A month later, the peace process had shattered and, amid the chaos, Erdoğan forced a rerun, when the HDP lost almost a million votes and the AKP returned to power.

This time, Demirtaş spends his days reading newspapers and watching television in a prison near the Greek and Bulgarian borders, 770 miles from his family in their hometown of Diyarbakir. He trails in fourth place in the presidential race, polls say.

He is not the only HDP politician in jail. He’s joined by eight other lawmakers and dozens of mayors of southeastern cities rounded up in the post-coup crackdown. They are not accused of involvement in the failed putsch nor of engaging in outright violence — but of supporting the PKK, which is listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States and the European Union.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D6PRGECMLXvI

Should the HDP face exile from parliament, peace with the PKK will become even more remote, said Kati Piri, the European Parliament’s rapporteur on Turkey.

“It is a crucial party when it comes to finding a peaceful, negotiated solution to the Kurdish question,” she said. “The focus is on whether the elections will be free on the day itself, but the whole election environment, like Demirtaş being in jail, has been anything but free and fair.”

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which is sending election observers, has already pointed to unfair media coverage and emergency-rule restrictions on speech and assembly ahead of the vote. It described HDP complaints of an “atmosphere of fear” due to attacks on campaigners and the detention of party activists.

The HDP has warned the integrity of the vote is at stake after the government moved polling stations for at least 120,000 voters in the southeast for security reasons.

Those voters will have to travel as far as 35 miles to cast their ballots, said Gozde Elif Soyturk, who heads the independent monitoring group Vote and Beyond, which will post observers nationwide.

The move raises fears “it will be harder in the southeast to securely vote,” she said. “We expect that some people won’t be able to travel, but still hope participation won’t decline.” She added that Vote and Beyond lacks the manpower to monitor about 4 percent of Turkey’s 55 million votes.

Demirtaş urged voters to safeguard their ballots in a televised speech, which state TV broadcast this week per election law. Thousands gathered to listen in a square in Istanbul, considered the world’s biggest Kurdish city as generations migrated there to leave violence and poverty in the southeast.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D4Z9TRbgaX9E%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

At the rally, Zeki Sezgin, a Kurd, said economic hardship and Kurdish cultural identity was driving more family and friends to support the HDP. “They won’t be fooled this time because someone brandishes a Quran,” he said.

Nearby, a woman held a cellphone up to capture Demirtaş on screen, tears streaming down her cheeks.

“Don’t worry about me,” Demirtaş said in the taped address from prison. “I will be free when you are all free.”

Ayla Jean Yackley reported from Istanbul.