Vodun children in Togo must dedicate their lives to the convent

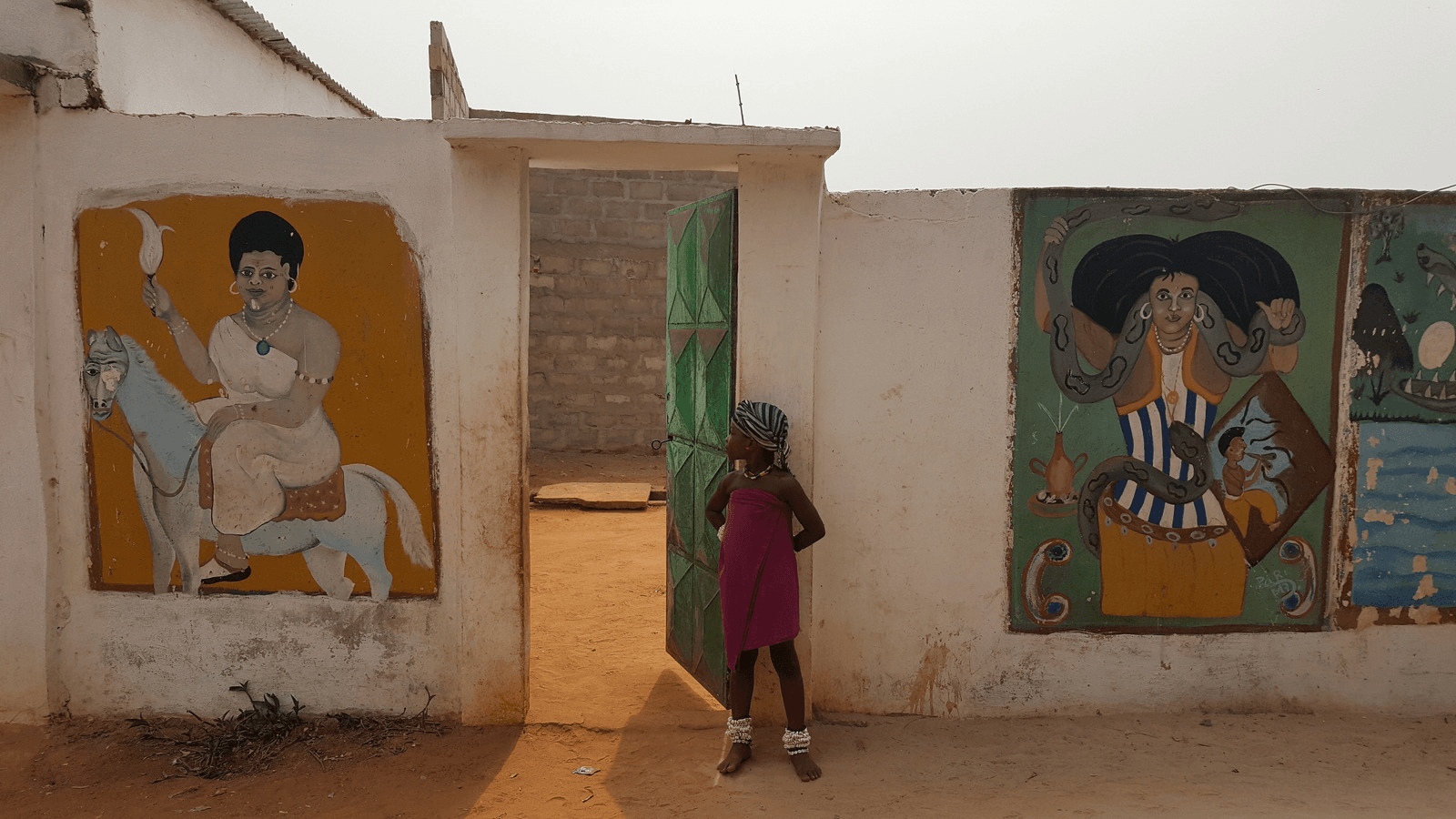

A young vodun initiate stands in front of the Anfoin convent, surrounded by images of vodun deities.

The walls of the vodun convent in Anfoin, a small village in the West African country of Togo, were painted with images of vodun and Hindu divinities. The 80-year-old mamissi, the convent’s head priestess, waited in a chamber covered in photos of her predecessors and depicting various vodun gods, whose cult she carries. Hers is one of many vodun convents spread across Togo, Ghana and Benin, where the West African traditional religion is amply practiced.

Vodun is an African religion that first appeared at the end of the 16th century on the shores of the Mono river, which separates Togo and Benin. The religion revolves around the adoration of the god Mawu through intermediary divinities represented in earthly objects. Father Bruno Gilli, an Italian priest who has lived in Togo for more than 40 years, explained that vodun divinities are separated into three main categories — celestial, sea and earth — based on the part of the world that they are responsible for. The world’s happiness is dependent on their collaboration.

To preserve and perpetuate the religion, children, both girls and boys, are introduced to the mysteries of vodun at a young age. Lasting one year, the initiation takes place in the convents, where the children are trained in worshipping one or several deities. Most children must remain in the convent for four months, after which they can return to their families and finish the initiation from their homes.

However, not all children are permitted to leave. Some are dedicated by their families to the convent and must remain for life, as they become their de facto property, catering to the demands of the priests and priestesses. They do not have access to formal education or healthcare outside the convent and are not permitted to be in contact with their parents.

The mamissi in Anfoin explained those dedicated are usually sick children whose parents are promised by the vodun priests that their kids will be healed if given to the convent; children of mothers who had not been able to conceive and promised that, were they to bear a child, they would give it to the convents; or children in special circumstances, who are “called” by the vodun gods to join the convent. Bruno Gilli added that children are considered to be summoned by the vodun through dreams, visions or surreal occurrences. Not responding to the calls is believed to expose the child and family to grave punishments.

Abdel Ganiou, a Togolese sociologist whose thesis focused on the traditional beliefs of the Tem populations of Togo, explained why women decide to cede their children to the convent and deprive themselves of the possibility of enjoying their children. According to Ganiou, women in Togo have traditionally the duty toward their husband, family and society to produce children. The inability to do so brings shame to the women and their families, leading them to appeal to the convents and fulfill their requirements, even if, in the end, this means giving up their children.

Luigi Pezzoli, an expert in West African vodun, emphasized that there are similarities between the young girls forced to live in the convent and the vestale, who were responsible for the cult of Vesta in ancient Rome. The difference is the vestale retired after 30 years of services and vowed to chastity, receiving a pension and being married off — usually to a Roman nobleman. Marriage to a vestale was considered a high honor and a source of good luck.

In turn, the vodun girls remain in the convent their entire life. Leaving the convent is difficult for them because they have no formal education and have been raised in complete dependence of the convent life without any reference system for the outside world. Exiting the convent means abandoning even the meager role they had and being rejected by a society that considers they are breaching their assigned social roles and that usually refuse to accept them back.

The initiated children — those who can leave the convent and those who cannot — are ascribed to one or multiple vodun gods, often having scars carved into their skin to symbolize their belonging to the respective gods. They sleep in designated locations and are looked after by the women in the convent.

They cannot attend school. International organizations, like Plan International, deplore the lack of access to formal education as a children’s rights violation. Still, there is a certain pedagogy based on oral traditions and the authority of the teacher, considered to be all-knowing.

The students are not supposed to know anything a priori, but are expected to listen and imitate. They learn sacred chants, dances and rituals specific to their respective vodun god or gods. They wear a specific initiation attire and are taught the vodun language, dissimilar to the one spoken locally and different among the convents from each region.

They are taught to forget their past, as they are being reborn: Upon entering the convent, they are given a new name by an oracle, according to the spiritual function of their life’s meaning.

The mamissi in Anfoin said that in the past, children used to be initiated at a very young age for more than 24 months. Now, the initiation takes place between the ages of 12 and 15. According to Hounongan Messan, one of the leaders of The National Federation for Vodun Cults and Traditions in Togo, the time spent by children in vodun convents should be even shorter: 45 days and only during school breaks. The Federation in 2017 started a vodun convent census covering all Togolese regions.

Some of the census’ key goals is determining the number of children in convents, their level of scholarization and professional training as well as identifying all priests and priestesses respecting ethical considerations. The first region covered was Maritime in Togo’s southern part. The census monitored over 4,963 convents and determined there were over 305 children being initiated for often up to two years, with their parents’ complicity. According to Hounongan, the children were nevertheless well looked after, facing no abuses or forced work. The four remaining regions will follow one by one until 2021.

Despite the substantial colonial efforts to suppress vodun as a devilish or primitive practice, the religion has survived and is now experiencing increasing popularity in Togo. While vodun is not an official state religion, as in Benin, over 50 percent of the Togolese population is believed to practice it. Many people still do so secretively, alongside Christianity or Islam, for fear they will be judged by colleagues, friends and communities as falling back into traditional, backward practices. As the West African religion continues to gain following, it can be expected that more children will be initiated in years to come, rendering it increasingly important to fully understand and improve their treatment in the vodun convent.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?