Editor’s note: To provide a full picture of what hate speech victims experienced, we have not edited out offensive language.

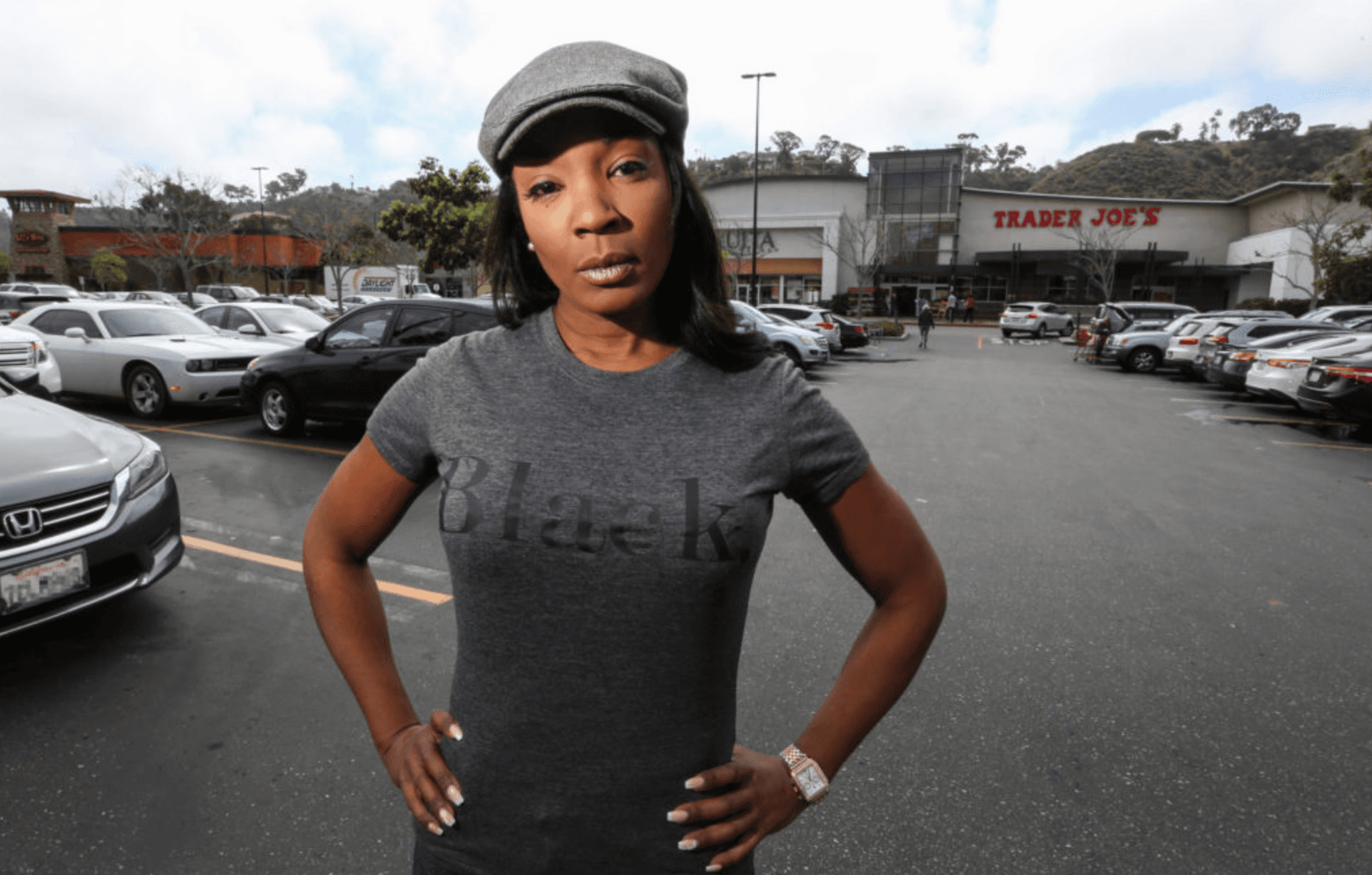

It was the day after the 2016 presidential election. Melissa Johnson was walking out of a Trader Joe’s in the heart of San Diego when a shiny BMW pulled up alongside her. The driver was a man in his late 30s. Dark hair. Green eyes. Her first thought: He’s kind of hot.

The car slowed down. Then the man shouted at her through the open window.

“Fuck you, nigger, go back to Africa. The slave ship is loading up,” he said. Then he added an exclamation point: “Trump!”

As the man drove away, Johnson, looked around at the shoppers who had witnessed the attack. She was the only African American in the parking lot. Not one person met her eye. Nobody said anything. So the 37-year-old walked, stunned, to her car, where she sat and wept.

Nearly every metric of intolerance in the US has surged over the past 18 months, from reported anti-Semitism and Islamophobia to violent hate crimes based on skin color, nationality or sexual orientation.

This renaissance of hate features something new: xenophobic, racist and homophobic attacks punctuated with President Donald Trump’s name. To understand the scope of the phenomenon, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting identified more than 150 reports of Trump-themed taunts and attacks stretching across 39 states over the past year and a half.

Interviews with the targets of and witnesses to these incidents showed a striking pattern. The abusers had a clear message: Trump’s going to take care of a problem — and that problem is you.

This pattern extended across races, religions and sexual orientation. Two days after the presidential election, a gay man in Michigan heard a taunt from a group of men: “Trump is going to get rid of people like you.” A week later, a Jewish woman in Austin, Texas, said she heard exactly the same threat from a middle-aged white man as she lined up to buy groceries. Two months later, a Latino man in California said he was told by a white ex-girlfriend that Trump was going “get rid of the Hispanics.” By March, a black woman in Houston reported that she was told by a white man that Trump was going to “get rid of all you niggers.”

Immediately after the election, there was a surge in Trump-related taunts. But all last year and into this year, the threats kept coming: An Asian American woman in Hollywood, California, had her hair pulled by an older white woman and was told that she had to “go back to China” now that Trump is president. In the Washington, D.C., area, the Trump-tainted threats got so frequent and so bad that Mohammad Qureshi, a Muslim American man who works at the Dulles Airport Marriott, changed his nametag to John.

These interviews reveal the trickle-down effect of a president who has called Mexicans rapists, proposed barring Muslims from entering the country and denigrated certain nations as “shithole countries.” Sometimes the perpetrators quoted the president’s words nearly verbatim. Other times, they signaled that as far as they’re concerned, the country has changed in their favor now that Trump is in charge.

For most of those targeted, it wasn’t the first time they have heard hateful speech. But dozens of people interviewed for this story said we’ve entered a new era of hate — one of open, blatant shouts, not whispers. And now that hate features a presidential seal of approval.

Racism in America used to be more subtle, Johnson said. As she shopped for dresses and handbags at Nordstrom, she said the security guards would follow her. The old lady in the elevator would clutch her Louis Vuitton bag a little tighter in the enclosed space — never mind that Johnson has five of those bags herself. Neighbors discouraged their son from dating her.

Now, things are different.

“Trump is giving these people so much power, so that they feel as though they’re also running the country,” Johnson said. “These horrible, ugly people now have a voice. And I’m so tired of hearing it because I’ve heard it my entire life. But it was whispers before. Now they’re yelling.”

Reveal culled the reports of Trump-themed attacks from Documenting Hate, a media collaborative led by ProPublica that tracks hate incidents across the country. Overall, Documenting Hate has received more than 300 reports of people using Trump’s name in hate speech since the effort launched in January 2017. That’s out of about 4,700 total tips.

Reveal spoke with more than 80 people who reported the Trump-themed cases, and located another 70 that had been reported by other media organizations or confirmed with documentation.

Most of the victims of abuse by Trump supporters said they’re scared. But their fear isn’t just that they will be attacked again by people emboldened by Trump. They worry that America has taken a step backward after generations of civil rights gains.

Najwa Sebbahi, for example, witnessed a middle-aged white woman’s Islamophobic rant against several customers in a store in the New York borough of Brooklyn three weeks before the 2016 election.

“Trump is going to get rid of all of you terrorists,” the woman said. The attack culminated in the woman pushing a Pakistani American girl and the police being called. Sebbahi, who immigrated to the US from Morocco in her teens, said police refused to charge the woman with a crime, citing her right to free speech.

It’s not the only attack Sebbahi has witnessed recently, and she said things have become palpably different for Muslim Americans since Trump took office. The president’s hostility toward Muslims, including his push for a ban on immigrants from six Muslim-majority countries, has opened the floodgates of hostility, the 32-year-old said.

“Every time I’m in public with my mom and she’s wearing her hijab, I’m very cautious and I tell her: ‘Don’t even, like, try to interact with anyone,’” Sebbahi said. “I just don’t want any of these interactions anymore. I feel like some people are just waiting for the slightest mistake to start an attack against you.”

‘He will get rid of all of you’

While most of the incidents were verbal, some taunts turned violent.

The week after the 2016 election, 32-year-old Dusty Paul Lacombe was arrested and charged with attacking an African American man outside a convenience store in Texas. Lacombe, who is white, announced that he was a Trump supporter right before the attack, according to a police report. He wasn’t charged with a hate crime.

In January 2017, prosecutors say Robin Rhodes, a 57-year-old white man, attacked a Muslim American employee at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. They say he knelt, mocking Muslim prayer, and yelled: “Trump is here now. He will get rid of all of you.” He also is accused of shouting, “Fuck Islam.” Rhodes was indicted on hate crime charges two months later.

In February 2017, Brandon Ray Davis rented a scooter while on vacation in Key West, Florida. The 30-year-old North Carolina man spotted a gay couple riding bikes and ran into one of the men, shouting “Faggots” and “You live in Trump country now!” Davis was charged with aggravated battery with hate crime enhancements and pleaded guilty to lesser charges in a plea agreement. He was sentenced to probation and community service.

But even in the dozens of cases of Trump-related abuse that did not result in physical attacks, victims of the hate speech say they were left scarred.

Kelly Ha was walking to the bus stop one day in January 2017 near her home in Washington, D.C., when a middle-aged white woman suddenly screamed at her. Ha had stopped briefly in the middle of the sidewalk to search for something in her handbag, and this delay had sent her attacker into paroxysms of rage.

“Go the fuck back to China or wherever you came from,” the woman said.

“Trump should have started with people like you,” Ha remembered the woman saying. “You’re the real threat to this country.”

Ha, a 23-year-old Korean American who has lived in the US her entire life, was dismayed by the outburst. She has spent her life studying and working hard and has never considered herself anything other than just another American.

As she recalled the incident, Ha’s voice trembled and broke with emotion.

“You know, people have used (Trump’s) name to justify all sorts of things. And racism is really just the start of it,” Ha said. “Some people are just racist. They only see you for what you look like — the color of your skin or the color of your hair or what your face looks like.”

Dozens of people across the country said the same thing: What hurts most in these attacks is being told that you don’t belong in America. That you’re not welcome. That since Trump was elected, the country has been reserved for a certain group — a group that doesn’t look like you or dress like you or practice the same religion as you.

The more than 150 reports likely represent only a tiny fraction of the Trump-related hate speech going on every day. Most are never officially reported anywhere to anyone. Documenting Hate catches only incidents picked up by the media or in which people self-report. And Trump-tainted taunts are just a subset of a flood of hate speech and hate crimes that has been cataloged by Documenting Hate and advocacy organizations.

The number of hate crimes committed in 2016 reached a five-year high, fueled by a spike around the November election, according to official FBI hate crime statistics. The Anti-Defamation League reports that anti-Semitic activity such as harassment and vandalism of synagogues rose 57 percent from 2016 to 2017. The Council on American-Islamic Relations tallied a 24 percent rise in anti-Muslim bias incidents in the first half of 2017 compared with the first half of 2016.

“This dry kindling was already there,” said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “The president’s invocation of various negative stereotypes has both coalesced, solidified and, in some ways, normalized the stereotypes in a mainstream discourse.”

This mainstreaming of negative stereotypes has spilled over into an increase in hate incidents and hate crimes, Levin said. He pointed out that in the days after the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack, while candidate Trump was enthusiastically pushing his Muslim travel ban on Twitter and in public appearances, there was a surge in anti-Muslim hate crimes.

Reveal’s analysis showed that people reported being targets of Trump-inspired hate speech in at least 39 states. Most incidents involved angry shouts of abuse, sometimes in private and sometimes in public. There also were incidents of Trump-inspired property damage and graffiti on victims’ property. And Reveal confirmed two dozen incidents of people writing hateful notes, letters or social media posts specifically referring to actions Trump would take against racial or religious minority groups.

Attacks have occurred in tiny rural towns and liberal neighborhoods in major cities. People have shouted Trump-laced insults from car windows and threatened passengers on public trains and buses. Trump supporters have accosted shoppers in grocery stores and malls, on beaches and in diners. And even schools have become steeped in political poison as children interpret Trump’s words, tweets and actions in their own ways.

‘He’s trying to create a white world’

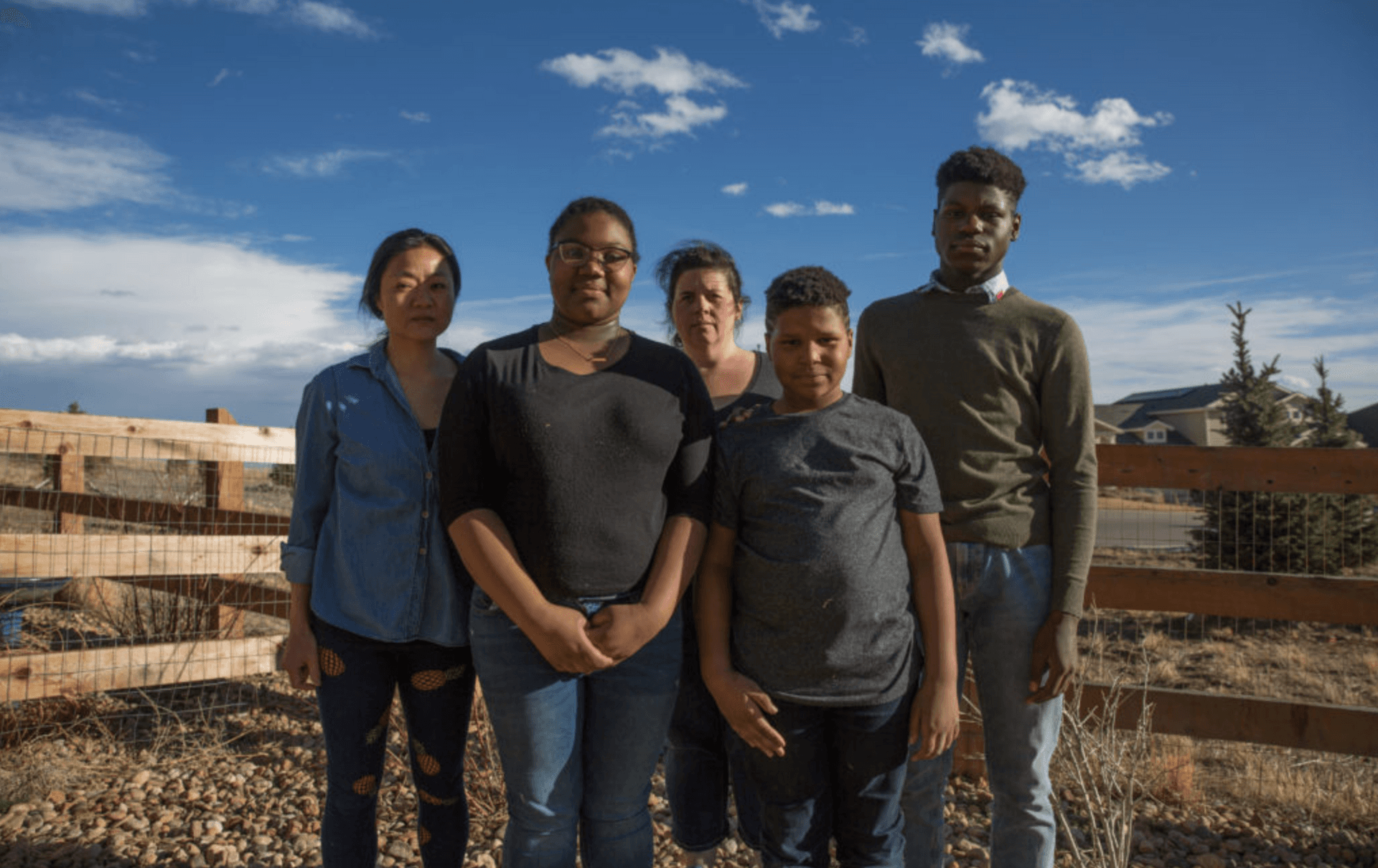

Growing up in Arvada, Colorado, was always going to have its challenges for Aaliyah, Chris and Khalil Stevens-Roesener.

The three biological siblings, who are African American, were adopted by their mothers, Jorie Stevens and Tara Roesener, in 2011. They live in a sprawling suburb northwest of Denver that is overwhelmingly white.

According to census data, Arvada was less than 1 percent African American in 2010, and little seems to have changed since then. Aaliyah, Chris and Khalil say they’ve always been among only a handful of black kids at school.

Still, 2011 was an optimistic time for Stevens and Roesener.

The US had its first black president. The country seemed more accepting every day. They didn’t believe racism was ever going to go away completely, but Stevens, who is white, and Roesener, who is Asian American, had hope for the future.

“You know, you’re still going to hear the occasional backwater person use the N-word, and that’s unacceptable,” Stevens said. “But we didn’t hear it as directly and as comfortably — the nasty things that people are saying right now.”

The kids dealt with isolated incidents of racism in their early years at school. But they largely brushed these off as anomalies. Aaliyah began dreaming of working for NASA, while Chris and Khalil got into football and set their sights on playing in the NFL. The color of their skin set them apart somewhat, but the kids never felt like they were targeted by their classmates.

Then came the 2016 presidential election.

Within a few months of Trump’s election, all three were targeted by explicit racist abuse at school. Thirteen-year-old Aaliyah was told by a white classmate that now that Trump was president, he could “shoot as many black people in the back as I want,” Tara Roesener said. Chris, 12, said his white classmates started ostentatiously using racial slurs in his presence, snickering at him when he told them to stop.

Khalil, now 10, said a white boy in his class started building a wall out of blocks during playtime. The boy purposefully placed the blocks between a group of white kids and a group of black and Latino kids.

“He said, ‘This is Trump’s wall,’” Khalil said.

Stevens and Roesener reported everything to the school district. A spokeswoman for the district said it has been receiving an increasing number of complaints about racial and political taunting.

Khalil said he thinks about the taunts he and his siblings have heard as he’s trying to fall asleep.

“At nighttime, I think about, like, what would happen if Trump did succeed in what he was planning to do, which he hopefully won’t,” he said.

Asked what he thinks Trump wants to do, Khalil was unequivocal. “I’m gonna say it like this: He’s trying to create a white world.” ![]()

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast. ![]()