Guatemalans are sending a record amount of money home during Trump’s presidency. Will their investment pay off?

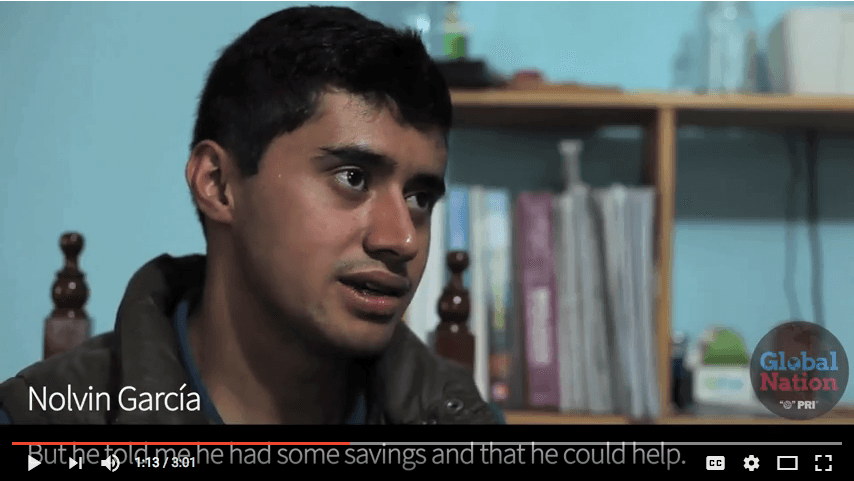

Video: What remittances from the US mean for one aspiring doctor in Guatemala

Nolvin García had never before received regular amounts of money from his relatives in the United States. That was not a problem for him. The 22-year-old and his family got along just fine, living in a small town in Guatemala’s western highlands. His undocumented relatives might send gifts for a birthday. But never large amounts of money, sent at regular intervals.

Two weeks after Donald Trump was sworn in as president, hundreds of dollars appeared in a local bank for García. A few weeks later, more than $1,000 arrived. By the end of Trump’s first 100 days, García estimated that his relative had moved at least $6,800 to Guatemala.

Through García, the undocumented relative who sent the money declined requests for an interview, citing the safety of his family. But he confirmed that concern over Trump’s immigration rhetoric was his reason for the transfers.

“He said perhaps it would be more secure in Guatemala,” García said in Spanish. “I told him that, that if he is deported, we could work the business between the two of us.”

In a country still wrestling with the effects of a decades-long civil war, more money is unquestionably good news. A tenth of Guatemala’s gross domestic product comes from remittances, or money sent from abroad. This year, Guatemalan immigrants are sending unprecedented amounts of remittances. But it is an open question whether an influx of cash will exacerbate problems of corruption and violence.

García, for one, had a very specific business he wanted to invest in with that money: his own. Whether his plan succeeds depends on how well he can navigate the same dangers that drove so many of those who send remittances to leave Guatemala in the first place.

This year, almost $7.5 billion has been sent from abroad, according to data from Guatemala’s central bank. That’s an increase of more than 15 percent from the same period last year and a record high for the country. The vast majority of that money — more than 97 percent — is coming from the US, according to a recent study by the United Nations. (The World Bank, which calculates remittances somewhat differently, reported even higher numbers).

Latin America, including the Caribbean, was the only region to see an increase in remittances last year, according to the World Bank. The increase has been particularly pronounced for countries like Mexico and Guatemala.

Sergio Hernández, a spokesman for Guatemala’s central bank, attributed the jump in remittances to an improving US economy, an increase in the number of Guatemalans living in the US (there were around 1 million Guatemalan immigrants in the US in 2015), and “recent announcements and actions that anticipate a more severe immigration policy by the US.”

One Guatemalan news report was more blunt, calling the increase the “Trump Effect.” Immigrants in the US, the report said, appear to be less willing to invest their money locally in case they are suddenly deported.

Edwin Castillo, an economics professor at Guatemala’s only public university system, said an increase in remittances had the potential to both help Guatemala’s poor and to artificially prop up Guatemala’s corrupt political and economic system.

“It is, sadly, a necessary harm,” he said, as he gestured like he was turning off a faucet. “We cannot close this job stream because this would generate even greater problems.”

The amount of money Guatemalans sent home has increased almost every year since 1994, the first year available in the bank’s public records. There have also been other spikes in remittances throughout that time. Since 2008, remittances generally increased between 4 and 9 percent each year. The beginning of 2015 looked like that trend would continue. During the first five months, remittances rose 8 percent compared to the previous year. But beginning in June, the month Donald Trump announced his candidacy, that number climbed to 16 percent over the rest of the year.

Still, many Guatemalans are not experiencing the boost. In interviews with more than a dozen people who reported receiving money from relatives in the US, several said that funds have actually slowed (or completely stopped) in the past year. Some attributed that to relatives getting fired for being undocumented. Others said family members in the US had become afraid to go to work.

For those who have benefitted, like García, success with the money is far from guaranteed.

One evening in June, García woke from a nap and shuffled into his family’s kitchen in the small town of Sigüila. His shirt bore the logo of a popular local pharmacy, “Farmacias Batres,” where he was headed for another night shift. He hadn’t had a full night sleep in almost a week. His two jobs wouldn’t allow it.

García had never planned to work at a pharmacy. But failing a psychology class grounded his plans for medical school: When you fail one class in a Guatemalan university, you’re not allowed to continue until you re-take that class. The fact that García is working toward medical school is, at least statistically, extraordinary. In a country where most people live below the poverty line, fewer than half of Guatemalan youth even make it past middle school, according to the United Nations.

García did have a few advantages. His father is a retired police officer who receives a pension from the government. The family’s washing machine, their 1992 Toyota Corolla and García’s purple braces all are indicators that García’s family could be considered part of Guatemala’s small middle class. It’s part of the reason they’d never received remittances before. They didn’t need it.

Inside “Farmacias Batres,” García gestured toward the front counter. “This is my first wife,” he said, referring to his night job. He then pointed back towards his home. “There, is my second wife.”

By “second wife,” he meant his day job, the place where all his remittances had been spent: his own fledgling pharmacy.

Money has long flowed between Guatemala and the US. In 1956, two years after the CIA orchestrated a coup that overthrew Guatemala’s democratically elected president, the US began sending the Guatemalan military what would today amount to millions of dollars. More money arrived when a guerilla movement popped up a few years later.

Over the next four decades, the US sent Guatemala almost a quarter of a billion dollars in military aid. During the same time period, hundreds of thousands of people were wiped out in an increasingly genocidal campaign by the Guatemalan army. Many Guatemalans who fled to the US were refugees of that civil war.

García is part of Guatemala’s first generation to only remember peacetime. Yet the war’s economic, political and human toll ensured a bloody peace. In recent years, the country’s murder rate has consistently been higher than many of its neighbors, including Mexico.

Unsurprisingly, “Farmacias Batres” paid a security guard to stay with García all night.

In the morning, after finishing his night shift, he made his first dangerous decision of the day: climbing into an overflowing public van for the ride home. This was dangerous for several reasons. Gangs often target drivers for extortion, sometimes murdering them in front of passengers, according to the research organization InSight Crime.

The man collecting the fare didn’t close the van’s sliding door, and the road blew by inches from García’s feet. Any error on the driver’s part and García would be launched into traffic.

“We are sardines,” García mumbled.

García arrived at his stop, paid for the ride, and walked more than a mile to his home. His mom was making breakfast, including beans grown in their fields and cheese from the family cows.

Now he was ready for his “second wife.”

To get there, he chose one of the few options more dangerous than a public bus: He rode his bicycle four miles up a mountain on a highway. There was no bike lane, only a deep concrete ditch to his right and a stampede of buses to his left. The vehicles adhered to no discernible speed limit. Clouds of smog blew in his face. An avid cyclist, he loved every moment of it.

He was barely winded when he arrived at his own pharmacy, located just outside one of Guatemala’s largest cities. García dismounted, lifted his bike onto the sidewalk and walked it inside.

Choosing to start a pharmacy was a logical choice for García. His night-shift job had prepared him, for one. But García also hopes to return to medical school. Doling out medicine keeps him in the game.

When García first pitched the idea of opening a pharmacy to his relative in the US, he wasn’t looking for money. He held out hope that a local cooperative might loan him enough cash to rent a space and buy supplies. But the relative liked the idea and jumped at the chance to move his money out of the US. Plus, he’d have a job waiting for him if he were ever deported.

“Farmacia Margarita” was named after García’s late grandmother and opened in April 2017. García quickly hired two employees.

Money, however, was tight. His biggest expense by far has been the medicine. He spent more than US$2,000 in early March to stock up on dozens of items. Combined with the rent and his employees’ salaries, there was often little left for himself at the end of the month. For the first few weeks after he found the location he wanted, he had to chip in some of his own savings to pay the bills. He certainly didn’t have the funds to spend hundreds of dollars for his own security guard.

García greeted Yoshi, the young woman working, then placed his hands on white metal bars separating the entrance of the pharmacy from the front counter. Previously, his only security had been a motion-activated camera.

He walked around the counter, bent down over a computer monitor and pulled up the sales summary. On Monday, they made about $16. Not ideal. The day after was better: almost $30. That was more normal. $30 each business day kept him on track to cover monthly expenses.

García slipped a handful of cash into an envelope and deposited it at a nearby cooperative. Now he could hustle. He grabbed a stack of promotional fliers from his store and began to work the town.

He approached a woman with an armful of corn, a young couple holding hands, a shop worker helping customers. One man was a friend from school who hadn’t heard that his former classmate was now a small-business owner.

Competition from the other pharmacies in town wasn’t the only thing García had to worry about. The gangs who extort bus drivers have also been known to threaten small businesses, and if that happens, there’s not always official recourse.

On a scale of 100 (not corrupt) to 0 (we’ve got problems), Transparency International recently gave Guatemala a 28.

There was a moment in 2015, around the time Trump announced his bid for president, when it looked like Guatemala’s shell of impunity might be cracking. That was the year mass protests precipitated the stunning downfalls of both Guatemala’s president and vice president, after each was implicated in a massive corruption investigation.

What happened next might sound familiar. A national election was already scheduled for that fall; one early front-runner was a left-wing political insider and former first lady. But the populace instead turned to a man who had never held public office, a man known primarily for his work on TV, who was sometimes accused of trafficking in racial stereotypes. The man’s entire campaign was built on his outsider status.

In October of that year, a former comedian named Jimmy Morales was elected president of Guatemala.

Two years into Morales’ tenure, and in the midst of an ongoing corruption investigation into the president, García was unimpressed. “The president is not helping the country,” he said, fliers in hand.

Back at his pharmacy, García ran his fingers across sheets of paper covering the back of a supply shelf. He wanted to replace them with something more permanent. He’d have to pay for it himself; his relative in the US was no longer sending remittances. The initial money he sent was supposed to be just start-up money.

The responsibility weighed on García.

In the early afternoon, García climbed back on his bike and headed down the mountain. As he rode, the temperature dropped and the mountains in front of him became a gray silhouette under advancing storm clouds.

García ate lunch with his family, took a six-minute shower, and was in his pajamas by 2:20 p.m. His next night shift started in a few hours. He wanted to be up well before then.

“If I’m not awake at 5,” he called out, “wake me up!”

“Five?” his mom called from another room.

“Yeah!” He closed the bedroom door.

Soon, he’d quit his “first wife” job down the mountain. He was going all in on “Farmacia Margarita,” with its metal white bars and its small security camera.

There was no security guard. García hoped he wouldn’t need one.

All interviews were translated from Spanish by Julio Castro, Gabriela Afre Dominguez, Abi Alvarado, Michael X. Sanders and Amy Nelson. This project was funded through grants from the Larry J. Waller Fellowship in Investigative Reporting and the G. Thomas Duffy Fund in Journalism at the Missouri School of Journalism, in addition to the Global Nation Reporting Fund for new contributors.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?