North Korea bombards South Korea with propaganda leaflets

South Korea and US soldiers stand guard during a commemorative ceremony for the 64th anniversary of the Korean armistice at the truce village of Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone dividing the two Koreas July 27, 2017.

North Korea has switched its printing presses into overdrive and is bombarding South Korea with propaganda leaflets in numbers not seen for decades.

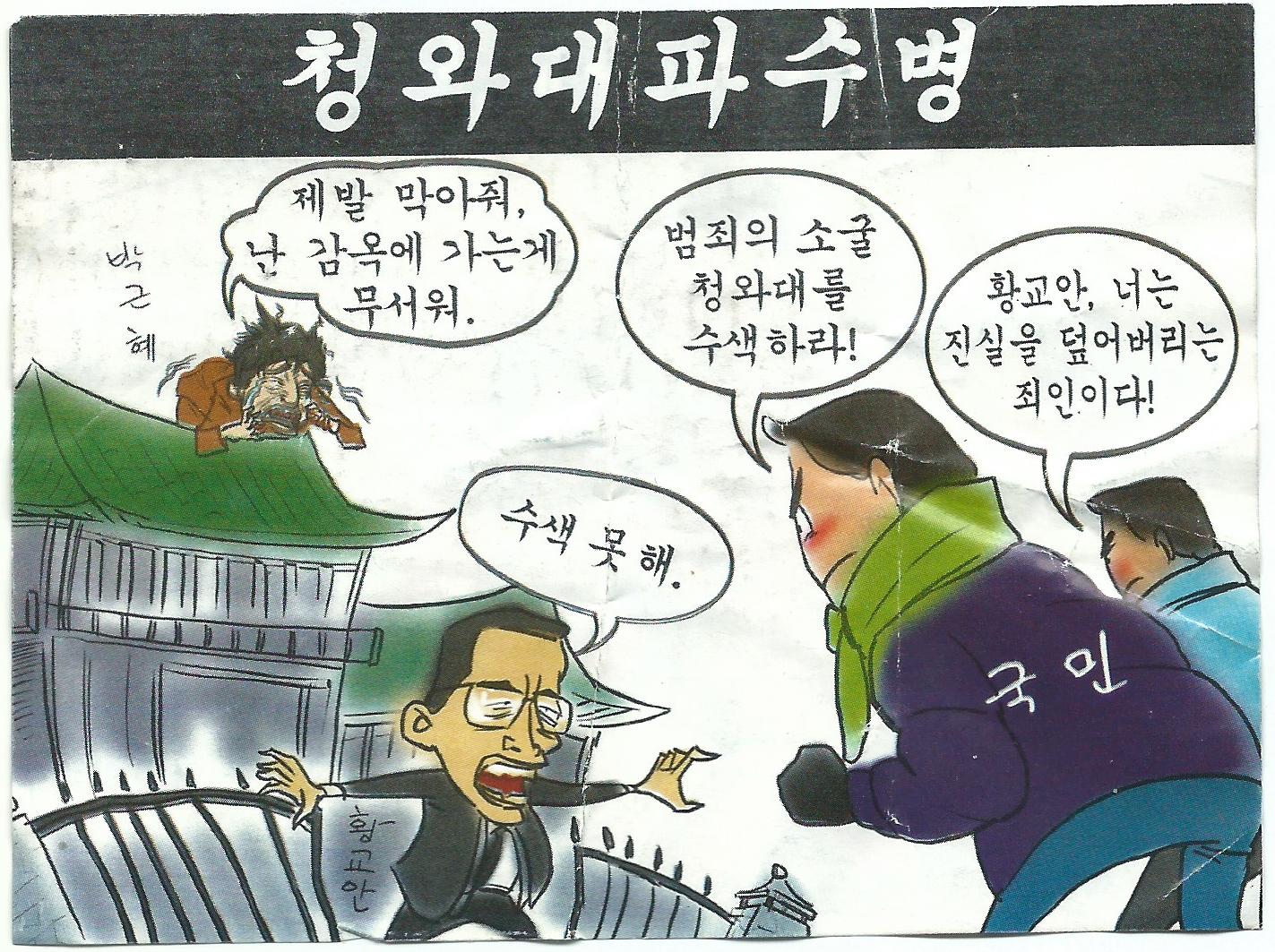

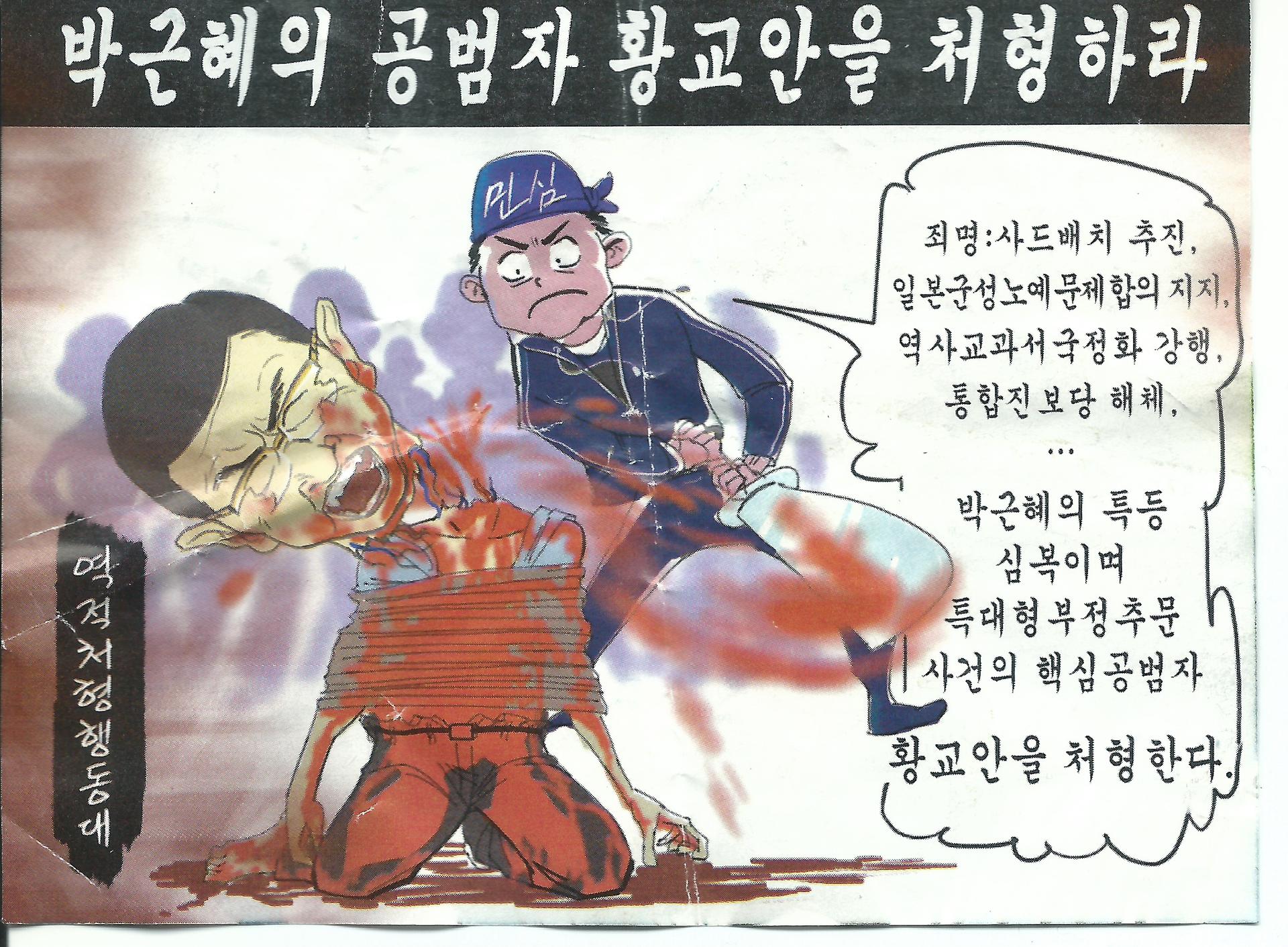

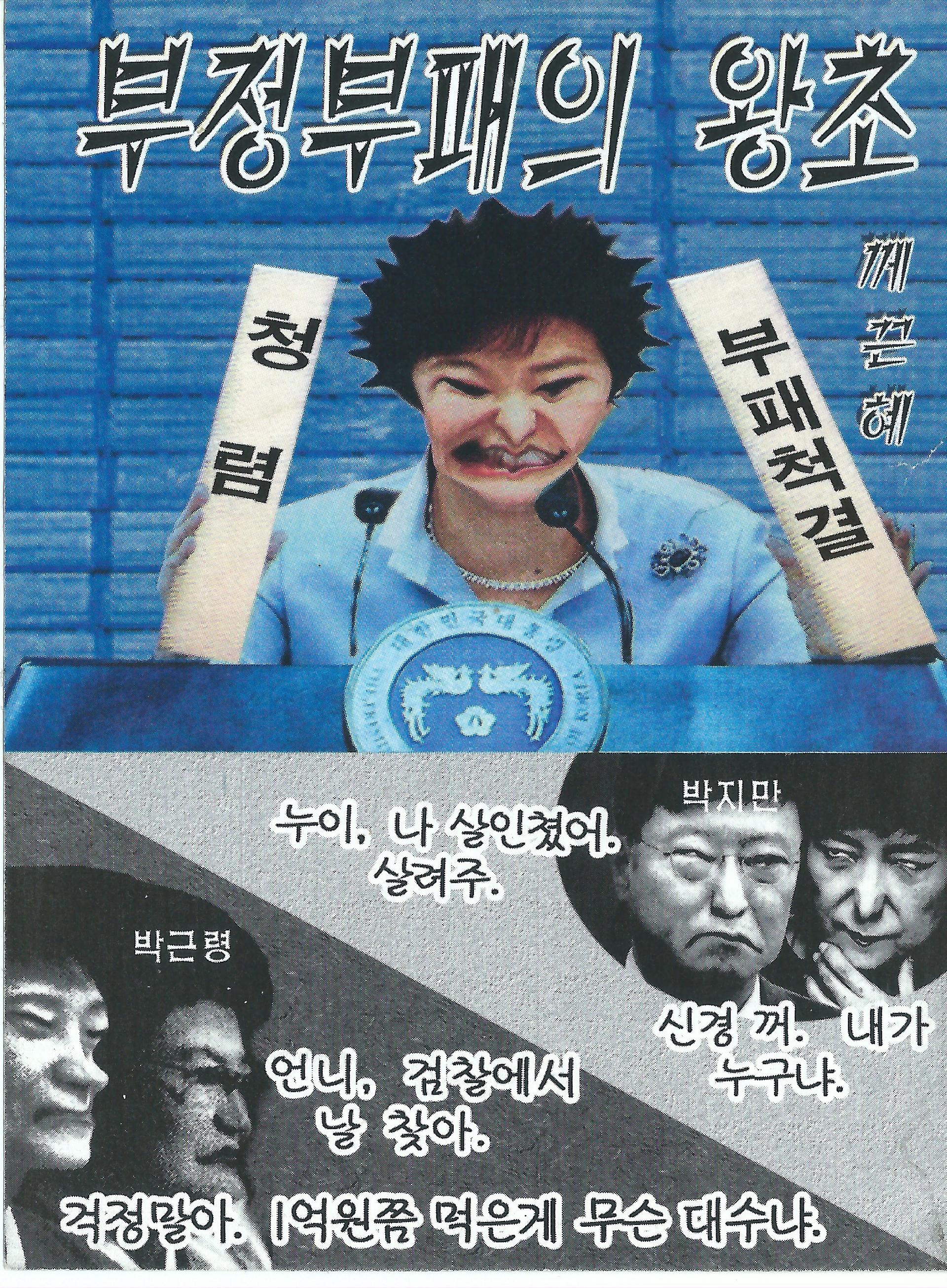

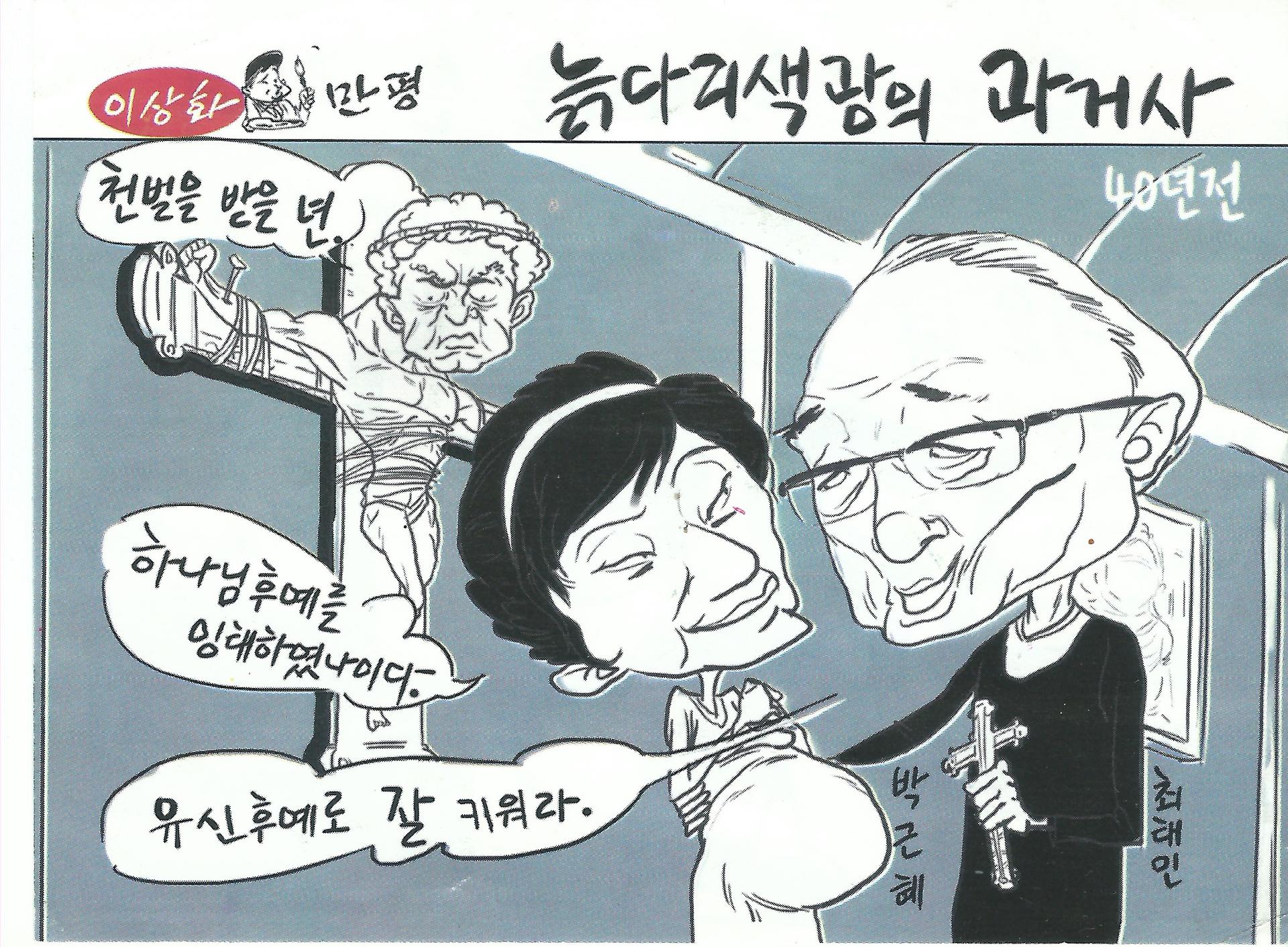

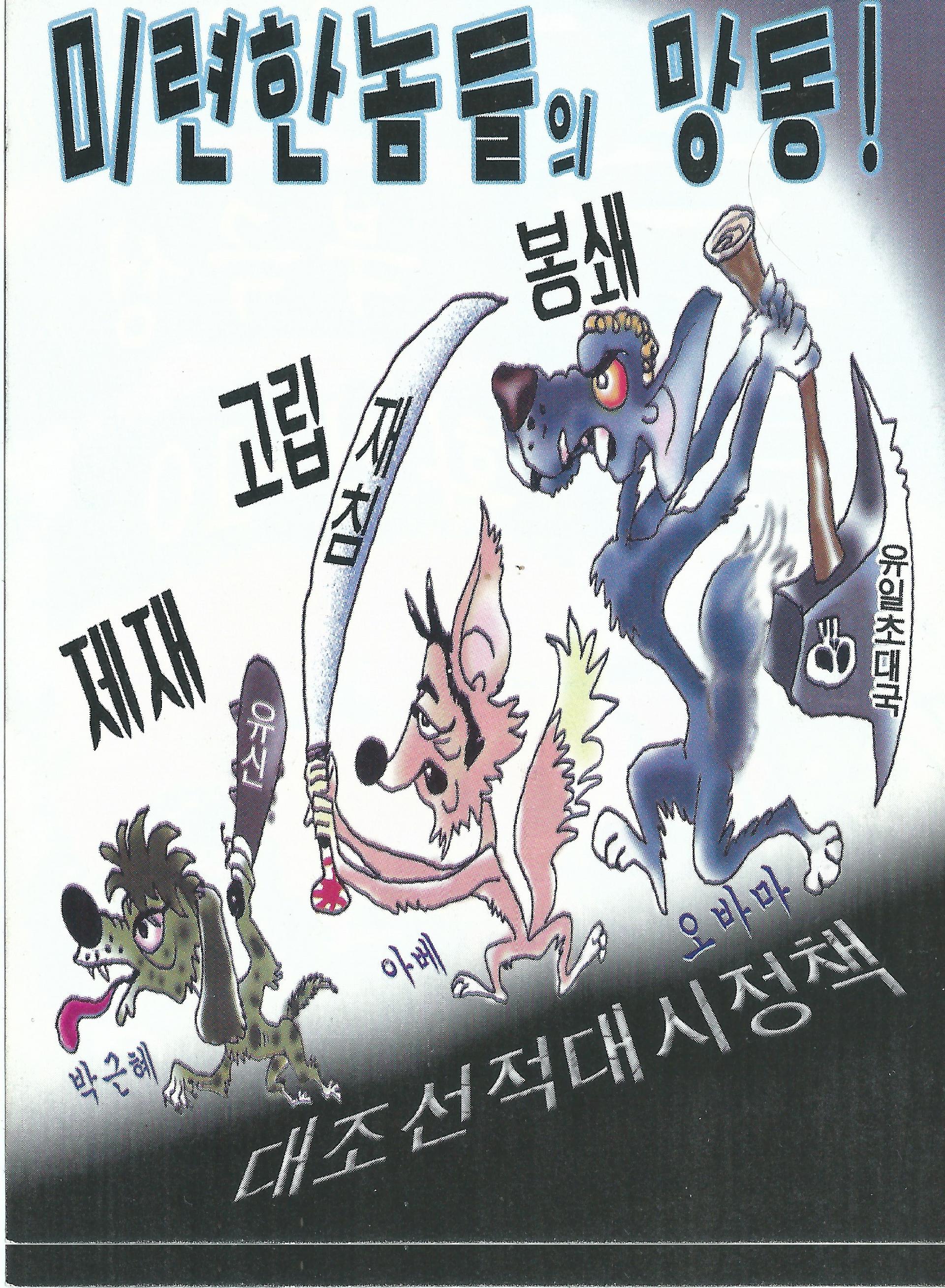

The papers, which feature both hand drawn and Photoshopped images as well as text, are Pyongyang’s “attempt at spreading fake news,” says Yoo Dong-ryul, who heads an independent research center in Seoul.

According to local media reports, more than 2 million of these papers have been found scattered on the streets of the capital and in provinces near the border since the end of 2015 — a volume not seen since the 1970s and '80s.

North Korea’s military is believed to send the flyers over the demilitarized zone via balloons equiped with timers that release their payload in seemingly random locations. In March, a group of hikers came across several of these glossy sheets of paper strewn along a wooded trail on Seoul’s Gwanak Mountain.

After one look at the images, they realized this was no ordinary litter.

Yoo Dong-ryul says the flyers are meant to deceive those who find them by displaying “made up names of alleged South Korean organizations” — an attempt to make them seem “more legitimate.” He adds that many of the leaflets found over the past year capitalized on public anger directed at Park, who was removed from office in March following months of mass demonstrations.Anti-Americanism is another common theme, Yoo says.

Pictures have also been shared recently on South Korean social media showing recovered flyers. Some of those include depictions of President Donald Trump and refer to him as an “old beast lunatic” — an insult North Korea has in the past translated as “dotard.”

In the past, both Koreas dropped subversive material into each other’s territory with the intent of inciting insurrection or defection.

The tactic has been used ever since the 1950-53 Korean War, when American forces sent millions of anti-Communist flyers into the North, according to the book "Bury The Enemy With Leaflets."

In 2004 during a period of rapprochement, the North and South Korean militaries agreed to end this propaganda war. But, some activist groups in the south, often run by North Korean refugees or churches, stepped up their own northward balloon launches. Their content ranges from DVDs of South Korean dramas to biblical passages.

Yang Moo-jin, a professor at the University of North Korean Studies in Seoul, says Pyongyang’s recent uptick in flyer dispersal is a “counter measure” to Seoul’s condoning of these groups as well as the government’s decision two years ago to resume loudspeaker broadcasts across the DMZ.

Missed the mark

The flyers are unlike other forms of North Korean propaganda art due to their “visceral violence directed toward a small group of people,” such as the ousted president Park, according to Jacco Zwetsloot, who researched North Korean comic art at Leiden University in the Netherlands and has reviewed dozens of the recently recovered papers.

“The leaflets are much more personalized” and are unlike North Korean propaganda posters, which depict “a violence that’s more general,” he says.

Zwetsloot says the leaflets’ content shows the authors have significant access to news and information from outside of their country, which is forbidden in the North. But, if their goal is to sway the minds of South Koreans with these pictures, “they missed the mark,” he adds.

“They are far too gory and gross,” says Zwetsloot, adding “you never saw this level of hate toward Park,” even from her South Korean critics.

In addition to their over the top violence, the new batch of flyers provides examples of Pyongyang’s version of satirical art.

“They’re quite playful in their ugliness,” Zwetsloot says.

Suspicions

Questions have been raised in local media as well as by some observers whether subversive domestic groups participate in the production and distribution of the leaflets, due in part to a lack of balloon debris at some locations and how flyers are found in the same place on multiple occasions.

Kwon Ung-man, an inspector at the Korean National Police Agency, says “there is no suspicion” that South Koreans are involved in the production of the propaganda flyers and no arrests have been made in connection to the papers’ dispersal.

Some analysts say the text of some flyers might reveal their origins.

The way the two Koreas speak their common language has diverged over the decades and some words or expressions have taken on differing nuances or are not mutually understood.

Kim Seok-hyang, a professor in North Korean studies at Ewha Women’s University and author of a book on the Korean language divide, pointed out a handful of North Korea-only words and phrases that appear on some of the flyers.

Those include the word jechim, a word only used in the North that means “re-invasion” and chodaeguk, another northern expression that translates as “super power”.

Terms like these are “not natural to South Koreans,” she says, but notes that other words on some of the papers don’t make sense in either North or South Korean vernaculars.

The awkward writing on some leaflets could be explained by North Korean propagandists’ attempts to sound more South Korean, but getting it completely wrong, explains North Korean defector Ahn Chan-il.

“The writers try to use South Korean terminology as much as possible,” he says, but they sometimes “get confused about which are the right words.”

It is for these reasons, say some observers, that despite North Korea’s renewed attempt to influence South Korean public opinion with propaganda leaflets, the effort might not be worth the paper it’s printed on.

“People do not take the information on these flyers seriously,” says analyst Yang Moo-jin. “Most South Koreans just laugh at them.”