How a rapper’s radio interview revealed a Saudi soft power campaign

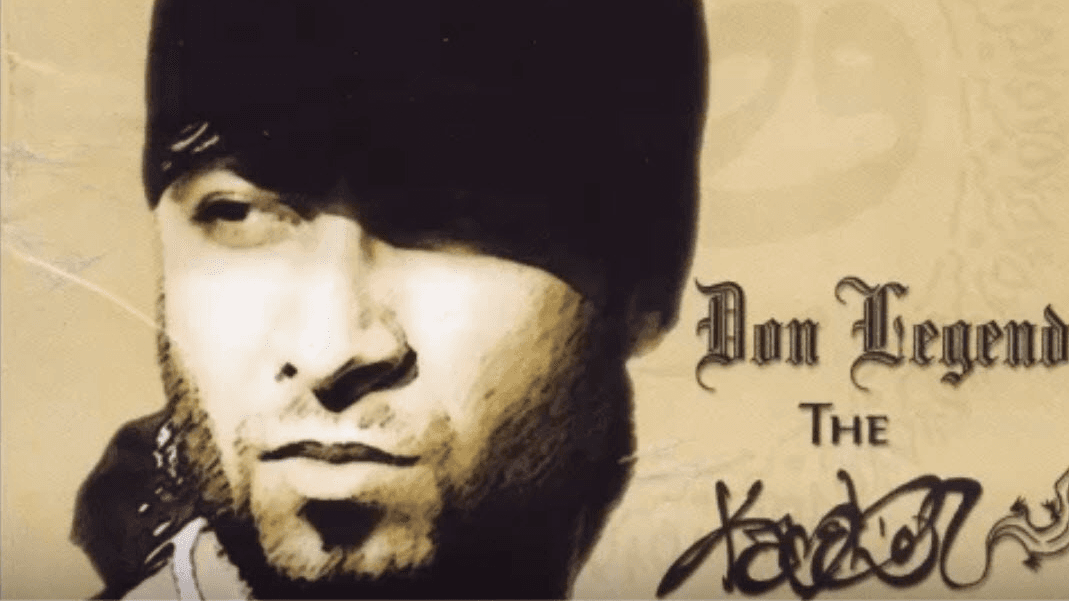

Saudi rapper Qusai Kheder on the cover of his album "Don Legend the Kamelion."

Is a foreign government funding that interview you’re reading or the podcast you’re listening to?

In early August, The Takeaway received an email with the subject line: “Feature Idea: The Middle East’s #1 Hip-Hop Artist Tours U.S.”

The email was from a communications firm in Washington, D.C., Keybridge Communications. The organization offered an interview with Qusai Kheder, which the email claimed was “the first person to ever record a rap song in Saudi Arabia.”

Qusai, who is also known as Don Legend the Kamelion, was born in Saudi Arabia, spent his teenage years in the US, and returned to his home country, where the story goes that he quickly made it to the top of a supposedly nascent underground hip-hop scene in the country.

There, Qusai ascended through the Saudi entertainment world, and is now the host of “Arabs Got Talent,” on one of Saudi Arabia’s largest television networks — The Middle East Broadcasting Center, or MBC.

His rise, the email claimed, represents a “vibrant new era of independent artistic expression,” and even “the resurgence of freedom of expression through music across the Arab World.”

It was one of the dozens of pitch emails that The Takeaway receives daily from large PR firms, think tanks, individuals offering up their self-published books, and more. And the story of what those pitches represent, and where they come from, can often be just as newsworthy as the guests themselves.

The Takeaway was told that Qusai was in the United States for a short window of time as part of a cultural exchange program with The Middle East Institute, a prominent American think tank, which was contracted by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, a cultural center in Saudi Arabia funded by the Saudi state-owned oil company, Saudi Aramco.

The cultural exchange program is called “Bridges,” and its goal is to bring a number of Saudi young professionals — from poets to the country’s first female lawyer — to the West and set up talks, performances and media appearances.

The Takeaway interviewed Qusai.

“It feels great that my country finally approved of hip-hop music and hip-hop culture, and I’ve been doing this for many, many years,” he told The Takeaway's Todd Zwillich.

When asked about politics and how he can perform his art in a country with strict censorship laws, he walked a fine line, saying that he is here in the United States representing the Saudi government.

“I stay away from politics completely,” he said. “I’m not a politician, I am a musician, I am an artist, and first and foremost, I am a human being. Politics is not my field, it’s not my area, and to be honest, I don’t get involved in it a lot.”

Qusai told The Takeaway that he was simply trying to be himself and represent, in a positive way, where he’s from — the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

But as the kingdom transitions into the 21st century, the long-term stability of its rule might very well depend on how it’s viewed by the rest of the world, and individuals like Qusai are helping to push a favorable message.

Last week, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, vowed to return the country to “moderate Islam,” saying “what happened in the last 30 years is not Saudi Arabia.” In recent years, the re-branding effort has been helped by policy changes, like the decision to rescind the ban on women driving.

But it can also take on subtler forms, increasingly through the funding of and partnerships with Western institutions.

Saudi Arabia seeks to soften its image

In Qusai’s political stance, or lack thereof, Paul Cochrane, a former contributing editor for Arab Media & Society, sees ties to Saudi soft power, which the nation has been pushing for years. While it’s not alone, the kingdom has been getting those ideas out through American think tanks like The Middle East Institute.

“What [Saudi Arabia’s] been trying to do for decades, and it’s really upped in the last several years, is to really try and portray a more cultured, softer version of the kingdom, rather than it being a more hardcore Islamic society,” he said. “Because a lot of media’s not allowed to operate so easily and freely within Saudi Arabia, there’s some restricted images that we can see, or stories coming out. They want to control that story within Saudi Arabia, but also on how it’s projected and pushed outside of the kingdom.”

After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia began to aggressively push a new narrative about its country. For example, the satellite channel Al Arabiya was started in 2003 and was established by individuals with close links to the Saudi royal family. It also established networks like MBC. It was a way to show to the rest of the world “a more cultured, softer version of the kingdom,” as well as to combat the rise of other networks like Qatar’s Al Jazeera, Cochrane said.

It should be noted that Saudi Arabia is not alone in its efforts to push “cultural ambassadors” onto the airwaves to help create a positive image. The United States has carried out such operations since the Cold War.

“It’s really a common sort of thing to reach out and tell other people about your culture — the sort of soft power approach — that works fairly well to quite a degree,” said Cochrane.

While the Saudis work to create a new image with positive interviews from cultural ambassadors like Qusai, the kingdom has also arrested dozens of dissidents in recent months, which includes artists and poets.

“The Saudis, they wouldn’t have let any sort of rapper to go and represent them in the US,” said Cochrane. “Qusai was sort of chosen because he was the right sort of candidate. He wouldn’t be doing things that would’ve been really against the monarchy, or being overly political. Anybody that doesn’t go along with their version would not be a cultural ambassador.”

And that came through in his interview with The Takeaway.

Cultural ambassador

“I know my limitations, and how far I can go,” Qusai said. “In the United States, you guys have the freedom of expression. We don’t have freedom of expression in Saudi Arabia. We have these limits that you can reach, but this as far as you go, because you have to respect the culture, the religion, the tradition, the ethics and the morals.”

When it comes to the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, which was founded in 2016, Cochrane said the organization is, in many ways, “window dressing.”

“It’s showing a positive image of the kingdom in the US, so when you have the rapper [Qusai] coming there talking, and being a cultural ambassador, people think, ‘Great! Wow! They have rappers in Saudi Arabia? This is not what you’d expect,’” said Cochrane. “It’s a good way to show that you are more cosmopolitan and open than you really are.”

After the interview recorded, The Takeaway received some pushback from the Middle East Institute about Zwillich’s line of questioning, taking issue with the number of questions asked about Qusai’s political views. That prompted The Takeaway to find out whether the Middle East Institute has a stake in Qusai’s messaging. In a phone call, The Takeaway asked the Middle East Institute about its relationship with Saudi Arabia and about its cultural program.

“We are under contract to deliver an exchange program for them, which involves bringing 30 social movers and thinkers in the arts and cultural world to the United States,” said Dr. Deirdre Evans-Pritchard, director of cultural and professional exchange programs at the Middle East Institute. “We are part of more than one program in the United States. There's also an arts section and a film section and a comedy section.”

When asked how much funding the kingdom pays to the Middle East Institute for executing such a program, Evans-Pritchard aggressively pushed back, saying that she was “astonished” by such a question.

While Evans-Pritchard was astonished by The Takeaway’s question about funding, Cochrane was not.

“A lot of these think tanks and organizations are supposed to be transparent, particularly about where their funding comes from,” Cochrane said. “Especially if it comes from a foreign government. But this has been going on for years now within think tanks and other institutions. Particularly in the last several years, the Gulf states have been really active in this — there’s sort of been an explosion of think tank funding. And it’s not just in the US, it’s also in the UK, and it’s within think tanks and organizations within the Middle East or the Gulf itself.”

“This is affecting their credibility in many ways, and their objectivity, because they’re not going to do critical things or do critical research about the Gulf countries as a result,” he adds.

Funding sources

According to its list of contributions in 2016, the Middle East Institute received $281,703 for a grant to fund an exchange program from Tam Development LLC, the funder of the Saudi program, as well as $2 million from the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a Gulf Studies Program and $200,000 in unrestricted funds from Saudi Aramco.

The Middle East Institute sent The Takeaway the following statement:

"The Middle East Institute places a great deal of value on maintaining its reputation for non-partisan, independent research and analysis. We do not advocate for any one policy or position. We are known in policy circles for our diverse body of research, writings and conferences on issues ranging from the refugee crisis to climate change in the region.

"For that reason, MEI only accepts unrestricted donations from foreign governments, meaning the contributions we do receive are for the general support of the Institute's scholarship, programming and operations.

"As for the Bridges/Talks program, it was a contract for services carried out by MEI's arts and culture program. The program fulfilled a key MEI mission to inform Americans about the Arab world's rich cultural output by introducing them to Saudi cultural leaders, including rappers, poets, authors and women mountain climbers."

A version of this story originally appeared on The Takeaway.