Are young Chinese liberalizing as China’s political leaders crack down?

Riding bicycles in Beijing's Houhai neighborhood

One way to think about a century is to look at the generations that will shape it, and how their influences and expectations are different from the generations that came before. In few places is that difference more dramatic than in the generation coming of age in China, today.

China’s one-child policy started under Deng Xiaoping, in the early ‘80s, a time when China’s economic growth was just taking off. Chinese who have come of age over the past decade, and those coming of age now, have grown up in a peaceful, increasingly prosperous and powerful China.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

That’s radically different from what generations of Chinese had experienced. And this generation is radically different, too. It’s more tech-savvy, sophisticated and connected with the world — through the internet, through television and films, through travel. It’s also more urban.

During this generation’s lifetime, China’s population has gone from being not quite 20 percent urban in 1980, to almost 60 percent urban, now. At the same time, per capita GDP — the average income per person — went from about $300 a year in 1980, to more than $8,000 now, and rising. Think of what that means, in terms of the life you live, the people you meet, the expectations you have.

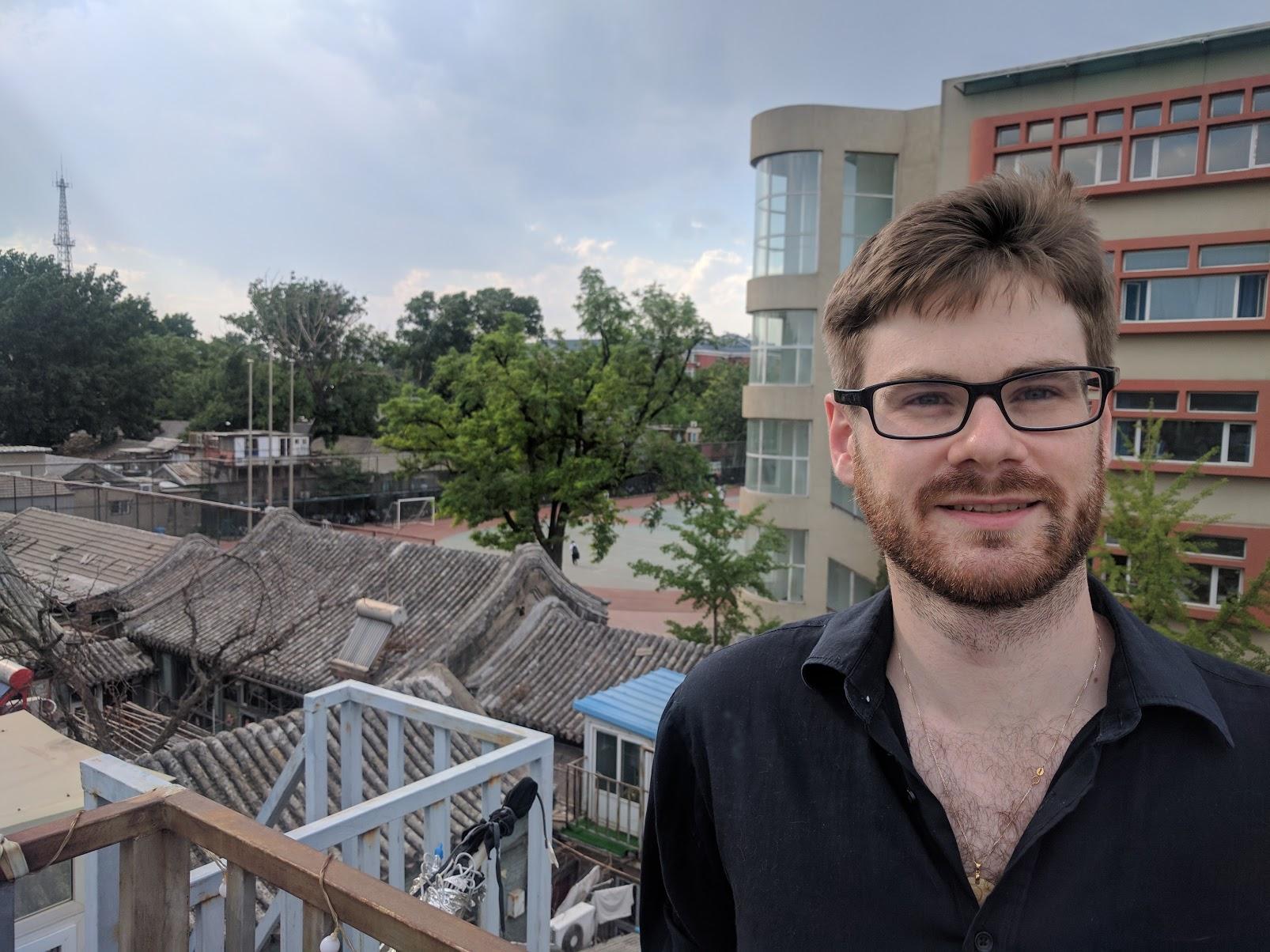

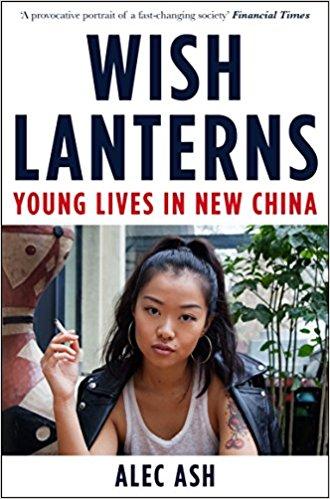

“I think sense of possibility is the key factor,” says Alec Ash, author of the book "Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China." The book focuses on six young Chinese adults, from disparate backgrounds, and the choices and challenges they have that set them apart from previous Chinese generations. He cites as an example, a young Chinese man who chose as his English name, Lucifer.

“His original plan was to be a rock star,” Ash says. “And when he realized that that wasn't working out, he thought 'oh, maybe it's because I'm singing in English. So he's formed a solo band, sang in Chinese. Then when that didn't work out, he went on dating shows and talent shows. When that didn't work, he opened a cafe. Now he's opened a second one. He is constantly reinventing himself. “

Of course, not every young Chinese adult reinvents himself or herself every few months, but there’s at least a feeling for many, that the possibility is there. Or was there? China’s economic growth is slowing, and as more Chinese have come online, President and Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping has strengthened censorship, banned many Western textbooks, and even discussion of what he apparently sees as such pernicious Western values as democracy, human rights and rule of law. That's a change for a generation that, in childhood, was encouraged to feel a more open sense of possibility.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

“For example, one guy my age, called Da Hai, who was very vocal on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, and had a very strong anti-authoritarian streak, he essentially gave up on that a couple of years back,” Ash says. "He got married. He has a car and a flat ) now, the supposed markers of having arrived in the middle class, or having succeeded in some way. But he tells me in as many words that he feels that he has compromised.”

But Ash says, he doesn’t see the tightening of space, the clampdown on expressing disparate views, to be permanent, or even decisive for this generation.

"I think [this generation of Chinese] is getting more liberal, as China's politics very clearly is getting more illiberal and more regressive,” Ash says. “I would even say that that movement towards political regression and clamping down at the top is a direct reaction to a liberalizing society and a liberalizing youth.”

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Ash cites the 330,000 Chinese now studying in the United States alone, “and that does have a knock-on effect when they come home.”

“Voices continue to be shared online, despite attempts to shut them down,” he says. “In general, perhaps to put it most simply, the cat is out of a bag. I don't think China, for all that it's trying, is able to … shut down all influence of ideas, however much the Education Ministry bans Western textbooks in universities. … China is part of a world now, and it will, as this generation grows up, will only see more engagement with the world from them. And I hope in a positive way.”

China's current generation of young adults is more likely than past generations to shape its own future, Ash says, rather than letting China’s political leaders define it for them. Many are nationalistic, in part thanks to a patriotic educational curriculum that started shortly after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, but Ash says he’s seen in Chinese his age an agility in bypassing government propaganda and shaping life on their own terms. Take as an example, he says, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s use of the term “China Dream.”

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

“His conception of the China Dream is everyone getting together behind the party, as China becomes the great, strong power in the world, and economically,” Ash says.

“Whereas, for this generation that I write about, and the China around me, it's more about the individual than the collective. It's about me, not about we. And so, those ambitions — right now I see a lot more of them at the individual level, a lot more of 'how can I change my life, or how can I get out of China?' — and a lot less of a collective ambition for 'how can I change China?’

“For many people in the cities, in this burgeoning middle class, and for many young people who already have a lot of the opportunities which those young people 20 years ago would not have had, the question is not now, 'how can I get rich?' The question is, 'what now?,'" he says. “And that's the big question for China as well. What now? What do we do now that we are becoming a rich country and a powerful country?”

How that question is answered, in this century, will matter to China, and to the world. And the generation of Chinese now coming of age, who have, throughout their young lives, surfed a wave of epic change, will play a pivotal role in finding the answers.

A note from Whose Century Is It creator & host Mary Kay Magistad:

When I started this podcast two years ago, the title “Whose Century Is It?” was meant to be both playful and provocative. I’d spent almost 15 years in China as an NPR and then PRI foreign correspondent, on either side of the turn of the century. And I’d heard, plenty of times, mostly in China, that if the 20th Century was America’s, the 21st would be China’s.

My feeling was, and is, that it’s not that simple. A century is a long time. And sure, China is rising, absolutely, but so is India, which has a much younger workforce, while China’s is aging. Also, by century’s end, Nigeria is expected to have a larger population than the United States. If it can educate and empower that population, and rein in corruption, it could be a force in the world, too, perhaps along with other African countries. Beyond that, why must a century belong to a nation-state, or to anyone? Surely, there are more interesting ways of thinking about who and what can shape a century, or any period of time, about what we can see coming, if we look in the right places, and what we can't.

Just think about how the world looked a century ago, in the late summer of 1917, people had no idea that a flu pandemic would start four months later that would infect 500 million people around the world, and kill 50 to 100 million of them.

They didn’t know that a few weeks later, in October 1917, the Bolsheviks would win in Russia, and create the Soviet Union, which would promote Communism around the world, nurture the Communist Party in China, dominate Eastern Europe and wage a Cold War against the United States that would shape most of the second half of the century. They didn’t know, fighting this war to end all wars, that a second world war would come slightly more than two decades later, bringing with it the end of empire and the beginning of the American Century — if you want to call it that.

They certainly didn’t know, probably couldn’t fathom, that by the end of the century, hundreds of millions of people around the world would have computers, mobile phones, televisions and cars, that they’d fly as easily as taking a train, that China would rise, and would be seen by many people around the world as a rival world power to the United States — in some cases, preferred to the United States.

Who knows what we can’t see, can’t fathom, from where we sit now, about what will happen next month, next year, in the next decade, or over the rest of this century? Who knows what technologies and tragedies, cooperation and conflict, opportunities seized, missed and scorned, will shape the coming decades?

And yet, it’s fun, useful, sometimes invaluable, to think about what we can see now that might matter going forward.

That’s been the project of this podcast.

And this is the last episode of the first long season of Whose Century Is It, two years, funded by the Henry Luce Foundation, and coproduced with PRI’s The World. Thanks to all who made this possible, especially Andrew Sussman, The World's executive producer, Jeb Sharp, a great reporter and editor at The World who liased with me to get segments related to the podcast on The World, and Jonathan Kealing, PRI.org’s executive editor.

Whose Century Is It? will continue, still available wherever you get your podcasts, with a new episode out the first week of each month. The archive of all 52 episodes so far will remain at pri.org/century, with a new website now in the works for future episodes. Keep listening!

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)