Sweden was among the best countries for immigrants. That’s changing.

For now, Hadi and Mahdi are living with uncertainty. They are lucky to be granted permanent residency in Sweden, but with rising anti-immigrant sentiments across the country, they live in their new home as an outsider. They don’t know if their family will join them or if they will face their future alone.

In a small Afghan restaurant in Malmo, Sweden, twins Hadi and Mahdi happily ate food that smelled of home. Their solo journey from Iran to northern Europe was traumatic and it sets them apart from their new Swedish peers.

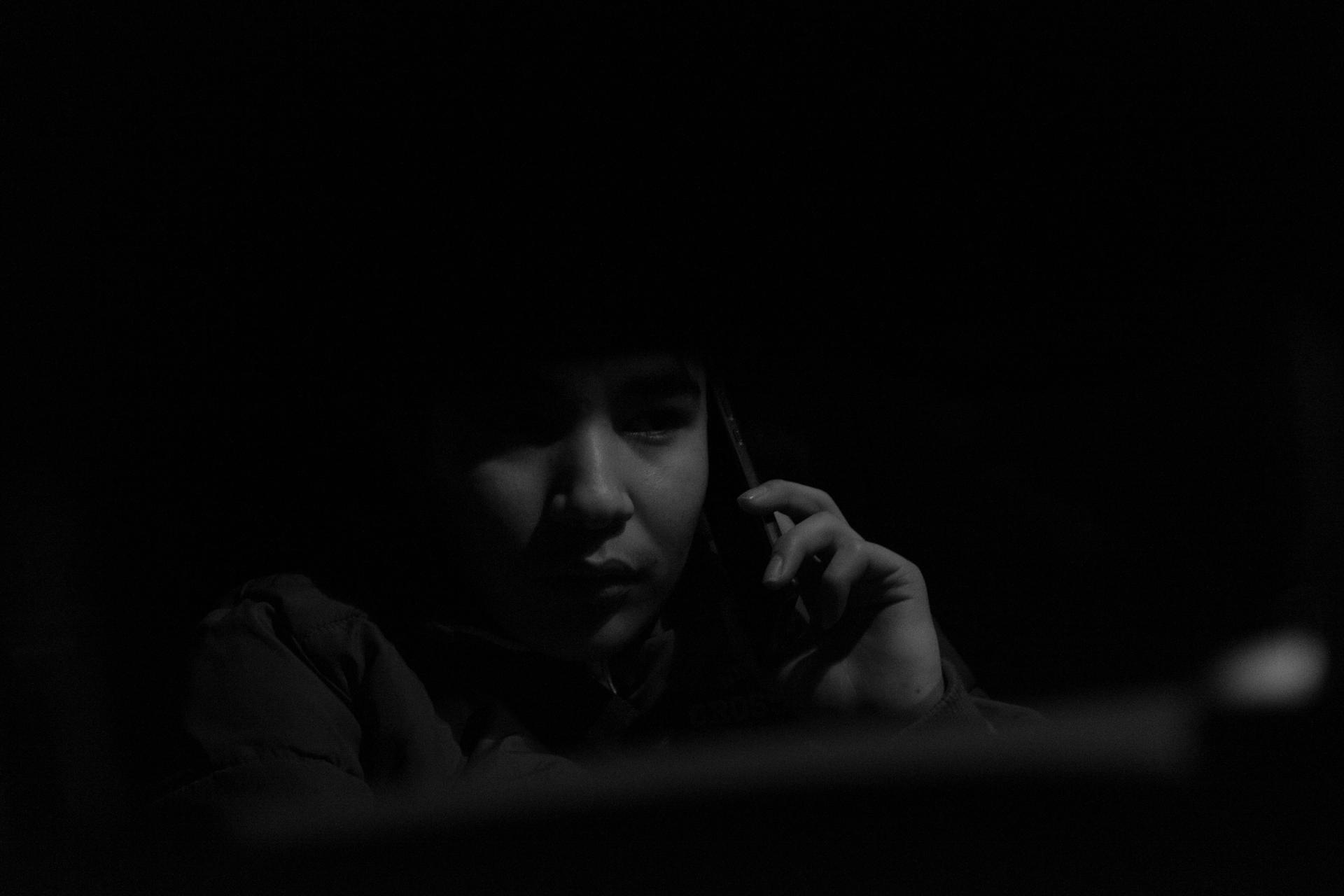

“I don’t feel secure telling them and I, at the same time, think they wouldn’t understand. At their age, I don’t think they could understand,” 13-year-old Mahdi explains. As they adapt to life in their new country, they wait anxiously to learn if their mother and four older sisters will ever be able to join them.

Sweden has been famously known for its welcoming attitude toward refugees and its commitment to family reunification. Until recently, it had the most generous immigration laws in Europe.

In 2014, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt made a famous speech urging Swedes to “open their hearts” to refugees seeking shelter. A year later, the population of just 10 million welcomed 165,000 asylum seekers to Sweden — more per capita than any other European nation.

The unprecedented number of newcomers has challenged the Swedish economy and has contributed to instability in the country's historically stable government. Now, immigrants like Hadi and Mahdi, must wait and see what happens in the 2018 election; a shift in political leadership would likely affect their opportunities in Sweden.

When they were just 8, the boys and their family fled Afghanistan. Their father was separated from the rest of the family at the Iranian border. No one has heard from him since. For the next few years, the boys worked at a bazaar in Tehran to help support their family. When the wave of Syrian refugees migrated to Europe, Hadi and Mahdi, along with 23,000 other Afghan children, followed them, winding up in Sweden.

In 2015, the boys won permanent residency in Sweden and are now on the path to citizenship. Although their mother and sisters still wait in Tehran, their story is a daydream for many young refugees who are waiting to be called for their first meeting with the Swedish Migration Agency.

Sweden’s social welfare state and high quality of life attracts many newcomers. According to Human Rights Watch, “Municipalities are responsible for providing housing, health care and education, as well as the appointment of a guardian to look after the child’s interests.”

Hadi and Mahdi were placed with Annika Noori, an exceptional guardian — known locally as a “good-man” — who has made it her job to advocate for their right to be reunited with their mother and sisters.

“It feels very good to have Annika as a ‘good-man’ because she is kind and she really cares about us,” says Hadi.

Sweden changing its ways

In, 2016, Sweden enacted a temporary law, valid for three years, that makes family reunification far more difficult. The law was retroactive to November 2015 and stopped recent immigrants who have received a residency permit from bringing their immediate family members to Sweden.

According to Daniel Hedlund, a post-doctoral researcher in the department of child and youth studies at Stockholm University, immigration policy is being tightened, though not entirely rewritten. Swedish migration law has long limited family reunification to nuclear family members. “Last link” immigration, for example, which permitted an adult sibling to come if he or she was the only relative left in the country of origin, was ended in 1997.

“To sum it up, these tendencies started much earlier, but have now played out to a fuller extent due to the current political climate in the country,” Hedlund says.

One of the measures in Sweden’s 2016 law is restricting family reunification to only those granted refugee status. According to the Swedish Migration Agency, “a person is considered a refugee when they have well-founded reasons to fear persecution due to race, nationality, religious or political beliefs, gender, sexual orientation or affiliation to a particular social group.”

In 2016, nearly a third of all residency permits granted in Sweden were for family reunification.

Hadi and Mahdi were first called to the immigration office a year after they arrived. A month later, they were given permanent residency; the Swedish Migration Agency granted them protection because their young age and lack of support system made them particularly vulnerable. But, they were denied refugee status as they did not face persecution because of their identity.

In spite of being the second largest refugee group in the world, Afghans face more difficulties being granted asylum than Syrians because European migration agencies have deemed many of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces safe and thus a reasonable place to deport asylum-seekers.

Erik Olsson, a professor of international migration and ethnic relations at Stockholm University, explained it was important to keep in mind that many refugees, like Hadi and Mahdi, left their country of origin at a young age — some without their family. They spent their early years in poor conditions and without legal rights.

“Many [children] were then exposed for different kinds of exploitation and corruption. Many were sent by their parents to Europe in order to escape the harsh conditions, including recruitment to the Shia brigades in Syria,” he says.

The new family reunification restrictions require Hadi and Mahdi to have refugee status for their mother and sisters to even have the possibility to follow. So, when their residency permit came, without refugee status, Noori immediately appealed. Just this summer, the courts declared the twins refugees.

The boys’ family now has three months to apply for residency in Sweden.

Political climate in Sweden

For the first time in history, Sweden is facing the possibility that no party or coalition will have the necessary 50 percent of votes to take control of parliament. The outcome of the 2018 elections will certainly affect the thousands of stateless people sitting in uncertainty, waiting to know if they will be granted residency in Sweden.

Individuals like Noori, who support integrating these new immigrants into Swedish society, represent a large percentage of the population.

“It is certainly true that attitudes towards refugees and immigration have become harsher in later years if we look at the statistics. However, without downplaying that that is a serious matter, a majority of the Swedes are still, for example, positive towards providing social rights to foreign born,” said Hedlund, citing a statistical report put together by Gävle College in 2016.

There is, though, a core group of Swedes who are fiercely against bringing more non-Swedes into the country. This sentiment has given rise to a political party that runs on an anti-immigrant platform.

The Sweden Democrats, not to be mistaken with the Social Democrats, are self-declared independent social conservatives. Founded in 1988, to the general public they are known as the far-right party; their roots are in Swedish fascism. Founding party leaders were active participants in the white supremacy movement of the late 1980s. In 2010, they received the 4 percent of votes needed to hold a seat in parliament. Since then, their popularity has steadily risen and they now have support from roughly 20 percent of the population — threatening the Social Democrats who have traditionally held an absolute majority.

This shift follows the anti-immigrant and anti-establishment trend seen across Europe and the US. The Sweden Democrats' outwardly racist ideologies do not align with Sweden’s goal of being a humanitarian power. Their unexpected rise is a reflection of populist concerns about the financial future in Sweden. For a country recently rated the best country to be an immigrant, asylum seekers are now facing deportation and local governments are seeing a significant decrease in funding for aid to recent immigrants.

“We had to close two homes this summer, six months earlier than anticipated, because of money,” says Anders Lundberg, who directs five homes for young immigrants, including the one where Hadi and Mahdi live. In 2017, his budget has been cut by 40 percent, forcing him to employ fewer personnel in fewer homes that are now filled with more children.

For those deported, they are often sent back to a country that they have never known and where there is no support system.

“[Swedes] opened our hearts and then all of a sudden closed them. … That is inhumane,” expresses Noori.

For now, Hadi and Mahdi, like many unaccompanied children, are playing a waiting game that started with a traumatic separation from their families.

“I do not think of the future. I think of the past and the present,” says Hadi when asked if he feels uncertain. “If my family comes, it will be better. If they do not come, what shall I do in Sweden?”

Rachael Cerrotti reported from Sweden.