Cartoonist freed but other journalists still held in Turkey’s controversial media trial

Press freedom activists hold copies of the opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet during a demonstration in solidarity with the jailed members of the newspaper outside a courthouse, in Istanbul, July 28, 2017.

There's one happy political cartoonist in Turkey today: Musa Kart.

A judge ordered Kart released from jail on Friday along with six other journalists and executives from Cumhuriyet, the country's oldest and most respected independent newspaper. But four other employees remain jailed, including the newspaper's editor-in-chief, an investigative reporter and a columnist.

In a deeply controversial trial that's been seen as a literal test of freedom of the press in Turkey, 17 staffers from Cumhuriyet faced charges that they aided terrorist organizations. Their arrests nine months ago were part of the Turkish government's crackdown after last summer's attempted coup.

The BBC's Selin Girit says this trial has galvanized Turks. "It is a watershed moment for press freedom in Turkey because Cumhuriyet is not an ordinary paper," she says.

Think of it as The New York Times of Turkey. Cumhuriyet was founded in 1924, just after modern Turkey was created. "It was founded on secularist priniciples. Those people who work at Cumhuriyet and those people who support Cumhuriyet say that it is actually the last remaining free press in Turkey," Girit says.

Girit spoke to Can Dündar, Cumhuriyet's previous editor-in-chief who is now in exile in Germany and also charged with aiding a terrorist organization. "He said if Cumhuriyet falls, there will be no more free press in Turkey," she says.

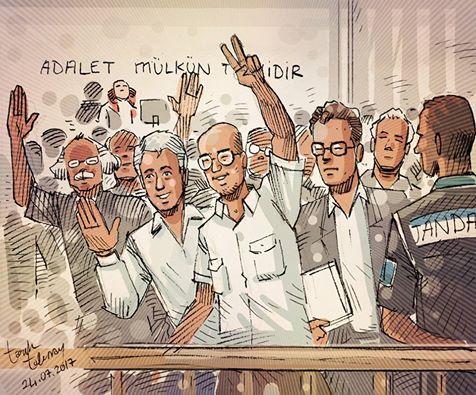

"The scene this week [at the courtroom] has been very emotional at times and very tense, too," says Girit.

The defendants have not been cowed. They've made powerful statements to the court, denying all charges against them and dismissing the case as politically motivated.

Girit says political cartoonist Kart managed to be both forceful and incredibly funny. Those in the courtroom couldn't help laughing. "It was as if we were watching a stand-up comedian but we were actually in a court," she recalls.

Related: Turkish female cartoonists get political — tackling oppression with humor

Kart described how he called a travel agent to book a hotel room in Bodrum, a tourist resort in the southwest of Turkey. "While I had been hoping to spend three days in a room with a sea view in Bodrum, I ended up spending nine months in a cell with a concrete view in Silivri," he says. "I don't think that my experiences can be passed off as a mere reservation blunder!"

But other defendants took a more serious tone.

"I am here because I am an independent, questioning and critical journalist, not because I knowingly and willingly helped a terrorist organization," Cumhuriyet columnist Kadri Gürsel, who remains in jail, told the court in his opening statement. "Because I have not compromised in my journalism, and I am persistent until the end. All these accusations directed to me are devoid of wisdom and reason, and are beyond the scope of any law or conscience."

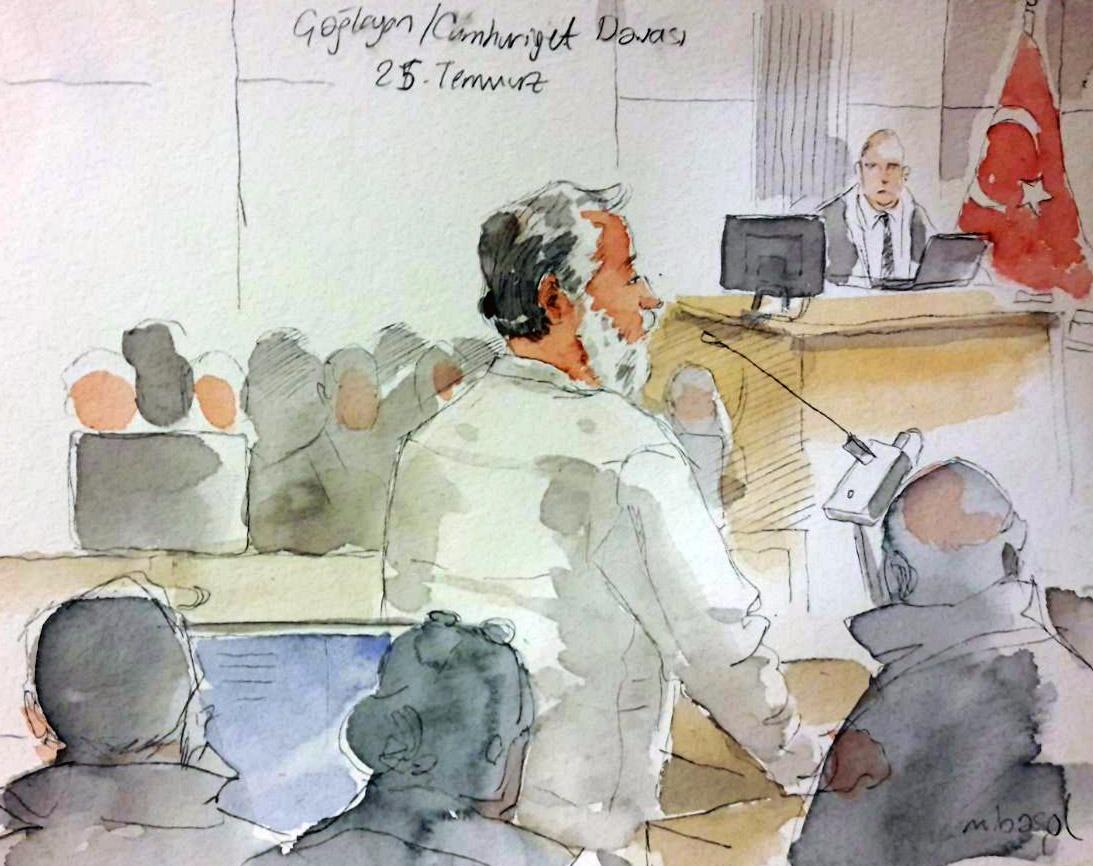

Ahmet Sik in court

When he took the stand, investigative reporter Ahmet Sik, who also remains in jail, refused to plead. "What I say is not defense or expression. On the contrary, it is an accusation," Sik said.

In 2011, Sik was detained for a year because of a book he wrote about Fethullah Gülen, the Islamic preacher Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blames for the 2016 attempted coup. In his statement to the court on Wednesday, Sik called the charges against him and the other journalists "trash." He called the trial an attack on media freedom and the judiciary a "lynch mob."

"They think we will be scared and silenced," he says. "There are not many remaining who are trying to uncover the truth. More than anything," he added, "we need more truth."

Girit says there's nothing funny about the sentences the Cumhuriyet journalists and executives could eventually face. "They could face from 7 1/2 years up to 43 years. They are charged with serious allegations. Aiding a terrorist organization is a very serious thing in Turkey, as it is in any other country. But the indictment is full of conflicting material," she says.

Cumhuriyet, the very newspaper that is on trial, has been covering the courtroom proceedings back to back, albeit with a reduced staff and a diminished advertising base. Companies are scared of government reprisals if they place ads in the newspaper. And ever since the arrests of their journalists, Girit says the newspaper has been reminding readers about the detentions.

"Just above the name of the paper on the first page, they have been publishing their names and beneath them, how many days they have been in prison," Girit says.

It's now nine months since most of them were arrested.

Cumhuriyet is also publishing blank columns of the columnists who are currently in jail so readers won't forget them.