State Department makes sea change on LGBT rights

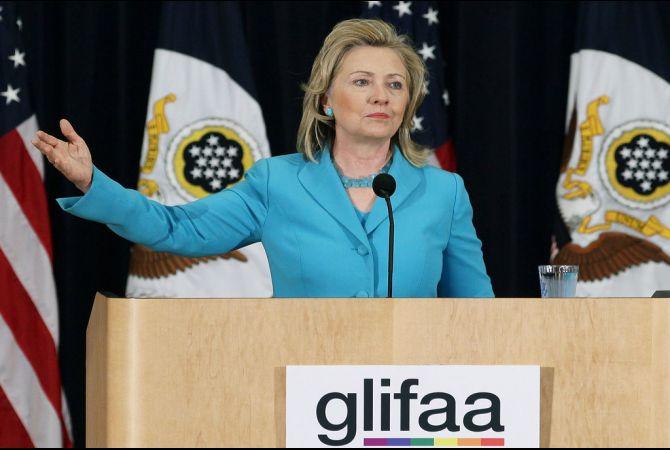

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton participates in a event co-hosted by the Department of State and Gays and Lesbians in Foreign Affairs Agencies (GLIFAA), at the State Department on June 27, 2011 in Washington, DC. During the event Secretary Clinton was presented with the GLIFAA Equality Award.

For decades the US State Department actively rooted out gay employees within its own ranks, deeming them subject to blackmail by foreign powers and a threat to national security.

Historians and former public officials say it began with a McCarthy-era campaign known as the “Lavender Scare” in which more than 1,000 State Department employees suspected of being gay or lesbian lost their jobs and the US also pressured United Nations and NATO allies into joining the campaign.

But that culture is being challenged as never before amid a sea change in the State Department, said James Hormel, who became America’s first openly gay ambassador in 1999 after a bitter and protracted confirmation process.

“I think the State Department has resolved its conscience about gay employees,” said Hormel, a philanthropist who has worked for gay rights for more than 30 years and is now retired from public service. “They’ve done a very dramatic turnaround.”

Building on protections placed by President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton closed the book on a legacy of internal targeting of LGBT personnel when she took charge of the agency in 2009. Now advocates and scholars say she has done as much to advance the rights of gay, lesbian and transgender people in recent years as any other leader in the world.

“The State Department has gone from the world’s principal advocate for anti-gay policy to one of the great leaders for LGBT rights,” said David K. Johnson, a professor at the University of South Florida and the author of “The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government.”

The 11,000-person American diplomatic corps is now engaged in a global initiative to promote LGBT rights as human rights, part of an unprecedented push Clinton announced at the United Nations in December. Its force has already been felt from Honduras to Malawi to Zimbabwe, welcomed by more progressive governments and condemned by a number of others.

“There have been results already,” said Daniel Baer, deputy assistant secretary at the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. “We’re pleased with the progress we’ve made.”

A memo issued by the White House on Dec. 6 was vague on whether the US would ever use the threat of withdrawing foreign aid to pressure countries with poor LGBT rights records, leading US officials to downplay any possibility that diplomats would do so.

But it is clear that American funding provides a backdrop to diplomatic efforts — even if the spending is proactive as with a new $3 million fund Clinton has launched for LGBT advocacy and support services. In short, the new initiative is more about carrots than sticks — an approach that has its critics.

These critics question whether this new policy will affect any change at all in religiously conservative countries such as Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan, where homosexuality is a grave criminal offense that can come with physical punishment such as flogging and in some cases a death sentence.

In countries like Pakistan and Russia, strong anti-American sentiment combines with social conservatism to create an inhospitable environment for LGBTs and a vehement resistance to US influence.

Next week, St. Petersburg city legislators will give a final vote on a bill that criminalizes pro-LGBT speech in front of children and equates it with pedophilia, and LGBT support group leader Olga Lenkova said US involvement may provoke unwanted consequences.

“There’s traditionally a very strong anti-American mood in Russia,” she said. “We’re worried that the Petersburg Legislative Assembly will now pass the legislation out of malice.”

But Baer stressed that human rights diplomacy is a slow and steady process.

“Over time, US commitment to LGBT rights with funding in tow makes all the difference in the world,” Baer said.

*****

A few months into her tenure, Clinton for the first time extended a host of services and benefits to the same-sex domestic partners of foreign service employees stationed around the world. With support from President Obama, Clinton had already begun to build the foundation of an unprecedented push for LGBT rights around the world that she announced before the United Nations in Geneva last December.

“To LGBT men and women worldwide, let me say this,” Clinton prefaced. “You have an ally in the United States of America and you have millions of friends among the American people.”

By equating LGBT rights with human rights in front of delegates from around the world, Clinton placed an emphatic punctuation mark on an approach she had been quietly implementing from her first day as secretary. The strategy includes hosting mixed events at US embassies aimed at bringing LGBT rights groups into closer contact with other rights groups as well as lobbying on behalf of activists who have been arrested by their governments.

“It’s so hard for most Americans, if they stop and ask themselves, to have imagined 15 or 20 years ago that in 2011 the US Secretary of State would give a speech on LGBT rights,” Baer said.

But in the last decade, global powers in Europe, Asia and Latin America have led the way in granting more protections for LGBTs, decriminalizing homosexuality, passing anti-discrimination legislation and in some countries legalizing gay marriage.

Although the United States, currently without federal protections for LGBTs in the workplace or at the altar, lags behind many of its partners, Baer argues that American efforts to encourage gay rights make sense as part of the US’ overall approach to human rights abroad.

“Rights-respecting countries make better partners,” Baer said.

The State Department’s new policy is already paying dividends. A number of Central and South American leaders who were already receptive to implementing gay-friendly policies have reached out for closer collaboration. Baer has also heard from “some places you wouldn’t expect,” he said, declining to name the countries for fear of stalling progress.

Former Ambassador Hormel, whose successful posting to Luxembourg in 1999 came five years after Fijian officials effectively blocked him from serving in Fiji, said he is encouraged by the state of the world regarding LGBT people’s civil rights.

Hormel said the emergence of international NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International as LGBT advocates in the mid-1990s helped pave the way for the UN to take a leading role on the issue.

In June 2011, the UN Human Rights Council passed a historic but non-binding resolution drawing attention to gays, lesbians and transgender people suffering abuses based on sexual orientation or gender identity. It was introduced by South Africa with support from the US.

A product of the resolution is a panel to be hosted by the Human Rights Council about LGBT rights on March 7, including delegates from around the world.

“Big moments at the UN are few and far between,” Hormel said. “Most changes take place in the tiniest increments.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.