Relatives and friends carry the coffin of Kimberly Palencia, a victim of a fire at the Virgen de la Asunción children's shelter, while arriving at the cemetery for her funeral in Guatemala City, Guatemala, on March 17, 2017.

After her dad had a stroke, 14-year-old Reina was brought to the San Jose Pinula public shelter near Guatemala’s capital with a promise she'd be taken care of.

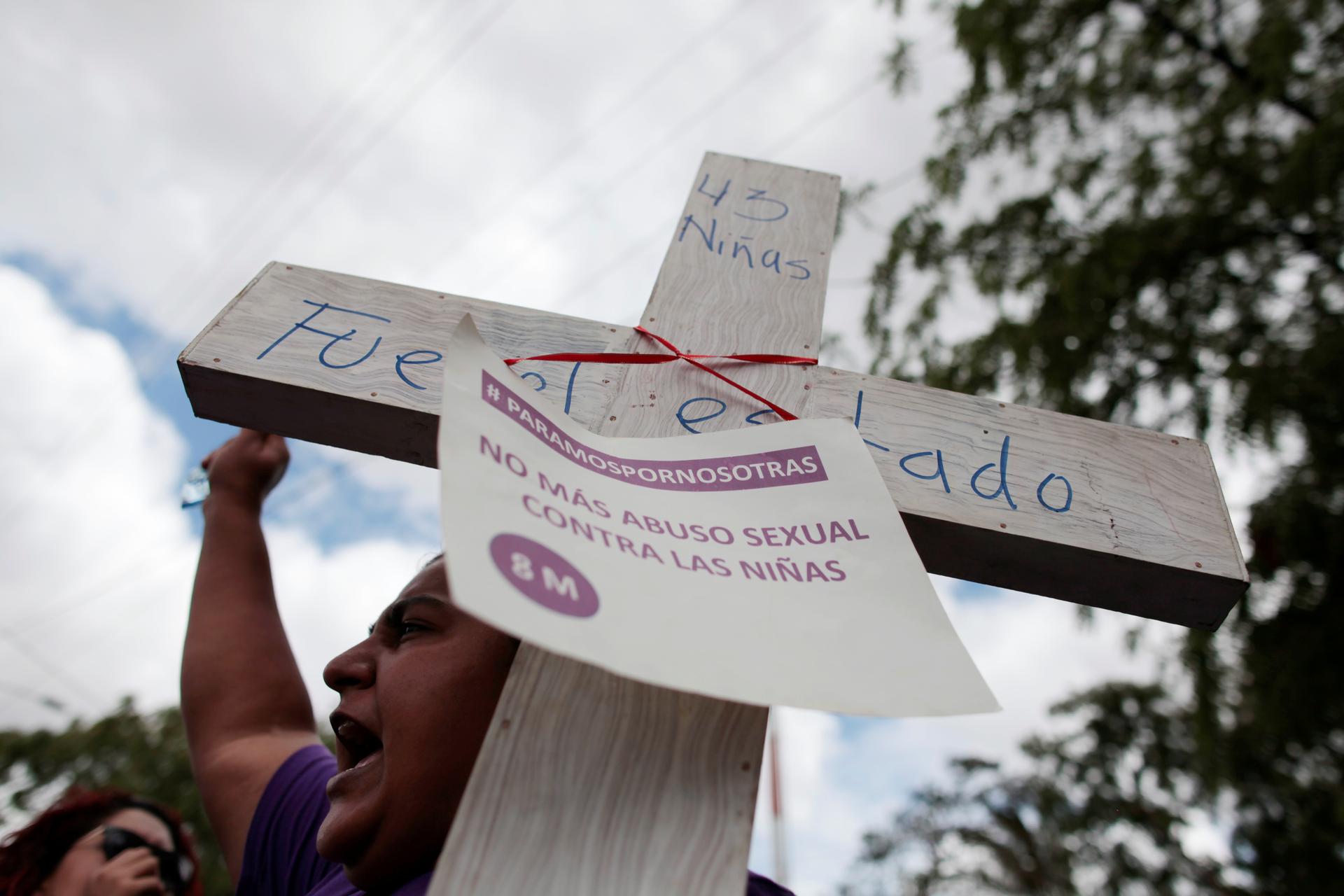

A riot and massive fire at the shelter earlier this month left 42 of Reina's fellow residents dead. The tragedy has focused global attention on this nation’s treatment of women and girls.

Guatemalan authorities aren’t saying yet what caused the fire, but more than 500 children and teenagers were at the shelter, and rumors abound of abuse, trafficking and neglect.

“They mixed girls who came from dysfunctional families or [were] abandoned with children and teenagers who committed gang-related crimes,” said attorney Paula Barrios, one of the lead lawyers investigating the case. “These public shelters were not run as temporary homes, where young ones can feel they have a better chance at life. By the investigations, it seems that they were there serving a prison sentence, deprived of their freedom."

Reina suffered severe burns in the fire and is one of many girls being treated at a local hospital.

Barrios said this tragedy was a long time coming. It was “an emergency no one wanted to see” with roots in the lingering, unreconciled aftermath of the 36-year Guatemalan civil war, in which thousands of girls were raped and abused, and few have been held accountable.

“There is an institutional and structural violence towards vulnerable populations, like women and children that continues nowadays and has its origins from the civil war [1960-1996]. Since then, government’s interests have been to keep the people silenced and unaware of the massacres and the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war against women,” Barrios said.

Guatemala holds the tragic distinction of being one of the worst countries worldwide in which to be a young woman. It has one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy, and the majority of those are a result of incest.

Rape by family or community members is one of the main problems that lead young ones to seek help at public and private children shelters. Between January 2012 and March 2015, statistics from the National Institute on Forensics reported 21,232 sexual abuses committed against girls and teenagers in the country, but only 1,275 cases resulted in court verdicts.

This type of violence has provoked civil society initiatives to record, reduce and prevent teenage pregnancy as well as to reduce maternal mortality.

“Guatemala City, Escuintla, Chiquimula, Retalhuleu and Quiché are some of the departments with highest pregnancy rates. We work with a majority of indigenous young girls with psychological and legal aid,” Mujeres Transformando el Mundo representative Jennifer Bravo said.

Guatemalan law prohibits abortion except to save a mother’s life, and that’s a problem, Bravo says, because “it obliges young girls to be mothers and then, does not provide help for them. These girls give birth and then have to quit school because they have to feed the child every two hours and do not have money to buy milk formulas.”

Maternal health and reproductive services are often expensive and unavailable to those living far from cities.

This critical situation led Dutch organization Women on Waves to initiate its first safe abortion campaign in Latin America. Its ship arrived in Puerto San Jose in late February, seeking to provide free health care services for women who lack access to safe abortions in their home countries. When they docked, they received about 300 calls from Guatemalan women. But the Guatemalan army would not allow women to board the ship.

This prompted many women to complain the government moves much more quickly to stop women from having abortions than it does to care for girls and young mothers in need.

“It has barely talked about the importance to solve the killing of the 42 girls at the shelter,” said activist Maya Maldonado.

“There is a need to reform the whole state’s children protection system, and it should start by recognizing that they are not objects but human beings who deserve respect,” Bravo said.

The Red Niña Niño network of organizations is leading efforts to reform the government’s approach to child protection by proposing changes to the current assistance program and the criminal code and by seeking monitoring by the international community. Bravo believes the government should provide reparations "to the young victims, who were fleeing vulnerable circumstances to enter a public system that has failed them.”

Reina was among the teen survivors who were transferred last week to a hospital in Galveston, Texas, to receive medical treatment. Her father, Lucas Nájera, was told his daughter died in the incident and was asked to identify her body — only to discover it was not Reina’s. When he found out she survived, he was appalled the government did not seek his permission before taking her out of the country. Nájera is yet to see his daughter.

Since March 8, children and teenagers who lived in the shelter have been transferred to different homes. There are few records available on their conditions. As the government continues to investigate, former Social Welfare Secretary Carlos Rodas, former Deputy Secretary Anahi Keller and Santo Torres, the former shelter director, have all been ordered detained.

Whether the tragedy will result in the government improving conditions for women and girls, though, remains to be seen.

Natalia Bonilla reported from Guatemala City.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!