Why are we so bad at spotting cons?

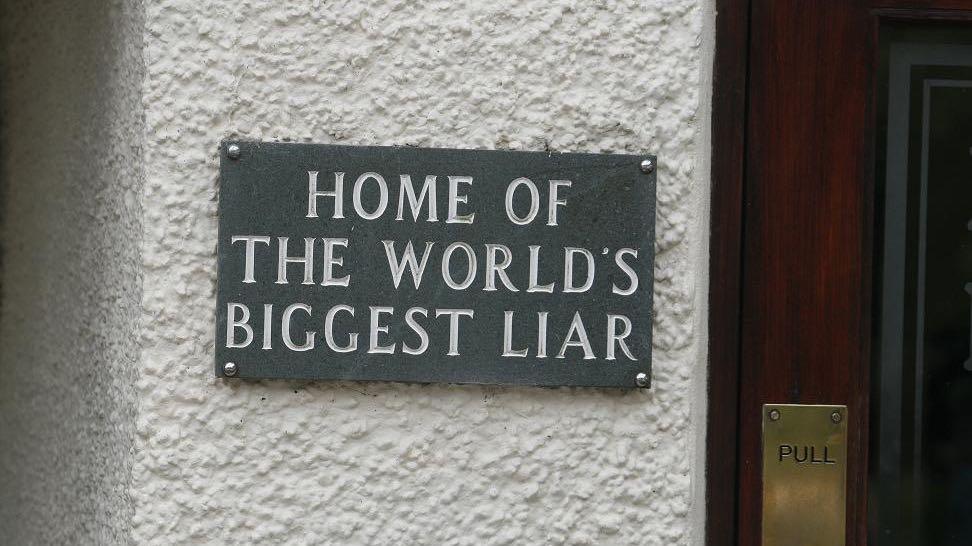

This is a sign at Wasdale Head Inn, Wasdale, Cumbria, UK.

At the turn of the 20th century, a con man named George C. Parker sold the Brooklyn Bridge multiple times. In 1920, Charles Ponzi was arrested after swindling millions of dollars in what’s now known as a Ponzi scheme. And from the early 1970s to 2008, Bernie Madoff made off with around $65 billion of other people’s money.

The details of each of these cons might differ, but the underlying nature of them — hucksters exploiting the trust of their marks — is strikingly similar. So, why do we fall for swindles like these? What makes us so vulnerable?

Maria Konnikova, author of "The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It … Every Time," has investigated those very questions, and she says that there are three main reasons.

The first is evolutionary. Konnikova says that, simply put, “We’re really really bad at spotting lies. We actually haven’t evolved to spot deception, and instead we’ve evolved to trust. It’s more advantageous from an evolutionary standpoint to trust other people.”

According to Pew, societies with higher levels of trust generally do better — socially, culturally and economically. And, Konnikova points out that the person who's going to survive in the wilderness isn’t the lone wolf, but someone who has the support of others. Not everyone can be Tom Hanks’ character in "Cast Away."

Plus, a lot of lies are "social lubricants," so we aren’t that inclined to notice them. After all, do you really want to know that your husband absolutely hates your new haircut? Or that your wife thinks you look terrible in those pants?

The second reason that we’re susceptible to cons is that we’re intrinsically hopeful as a species. Most people (excluding the clinically depressed) have an optimism bias. They think that tomorrow is going to be better than today. Cons and swindles with the lure of hope and promises of massive returns play into that.

And the final reason that cons ensnare us is that we’re inclined to believe that we’re exceptions to the rule. According to Konnikova, “When it comes to yourself, you never really think good things are too good. You think, ‘Oh, I deserve this.’”

Essentially, we all have a big blind spot, and it’s shaped exactly like us. In fact, one of the tips Konnikova offers is for all of us to think about ourselves in the third person. If your co-worker across the cubicle got a bunch of messages on OkCupid from a suspiciously attractive young man or had the “inside” deal on some land in Florida, what advice would you give them?

In short, there might be new cons, but the human nature they exploit doesn’t change all that much. Most people might not be jerks, but if someone offers you investment returns that look too good to be true, maybe do some research.

This story originally aired on Innovation Hub.