Revisiting the great Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali 30 years after his assassination

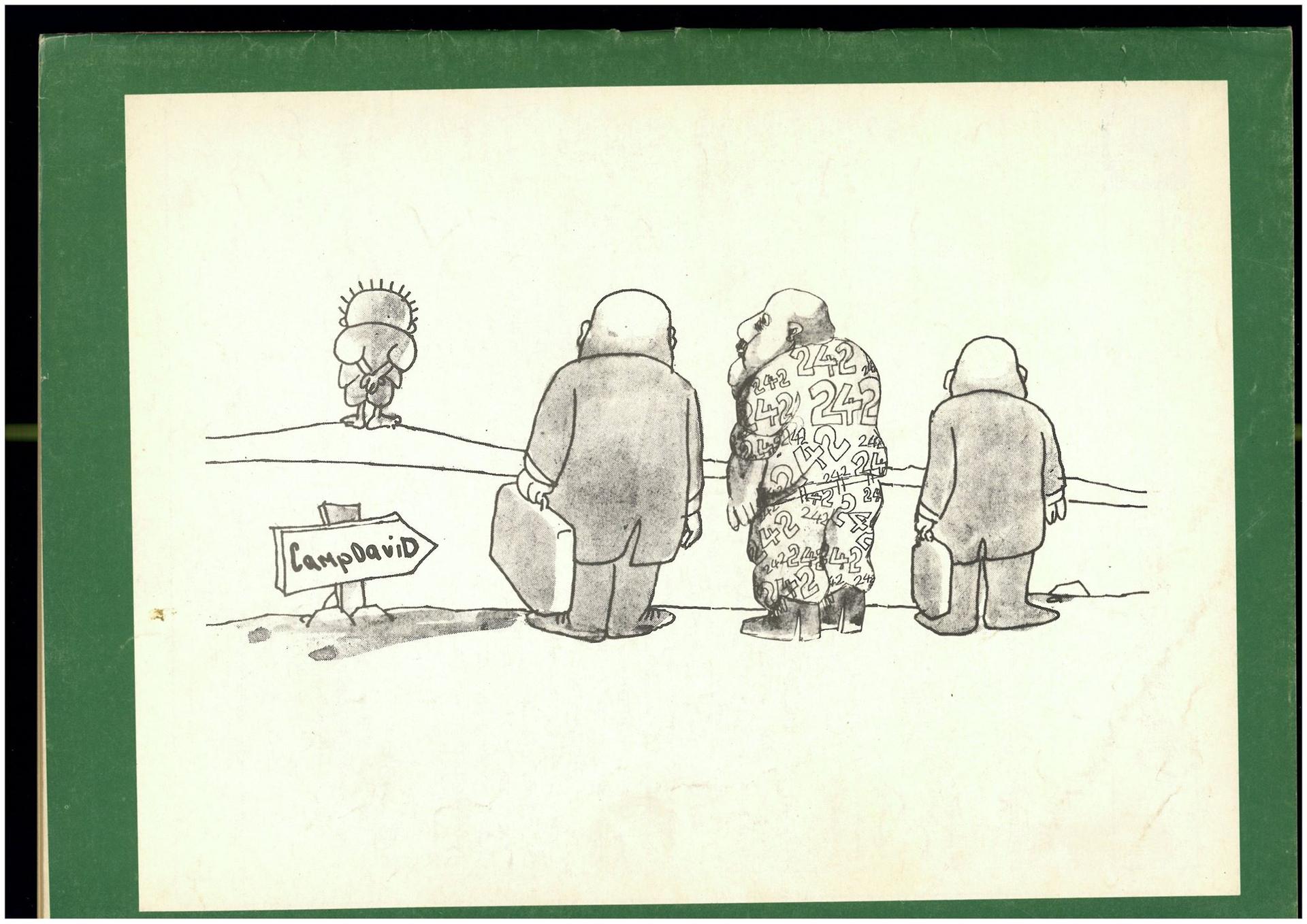

"The End" by Naji al-Ali, from the Lebanese newspaper Al-Safir, 1980.

Thirty years ago, the cartoonist Naji al-Ali was gunned down on the streets of London. Ali was a fearless critic of all authority and a Palestinian refugee. He had fled Kuwait three years earlier, after receiving death threats. His killers were never apprehended.

Yet his drawings continue to resonate for all those facing injustice.

This week, the London Metropolitan Police announced they were reviving the investigation into Ali’s assassination. It’s unclear what led police to reopen what has long been a cold case, or, at least, they haven’t been forthcoming about that.

But they have released a photograph of the firearm that likely killed Ali, a police sketch of the prime suspect and a detailed map of the street on which he was killed.

“[A] lot can change in 30 years — allegiances shift and people who were not willing to speak at the time of the murder may now be prepared to come forward with crucial information,” Commander Dean Haydon, head of the Met's Counter Terrorism Command, said in a statement.

Ali undoubtedly remains the most significant cartoonist in the Arab world. The anniversary of his murder and the reopening of the investigation is an opportunity to consider Ali’s aesthetic and political legacy in the Middle East and his enduring popularity across the world. His drawings continue to appear in graffiti and newspapers. At booksellers and literary fairs in the diverse Arab region, monographs of his iconic cartoons are almost always available, a signal of his lasting legacy.

The signature character of Ali’s cartoons is Handala, the young refugee boy — shoeless and in tatters — who witnesses the world’s tragedies on the reader’s behalf. Handala is a Palestinian refugee. But in the late Cold War era of power politics and geopolitical strife, Handala was also a universal story of the young boy whose innocence is lost. The reader never sees Handala’s face; his back is always toward us.

The cartoon character, Ali once said, symbolized his lost childhood as he had fled from a village near Nazareth in what was the British Mandate of Palestine, with the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 and the ensuing Nakba, meaning “catastrophe,” as the Palestinian mass exodus is known. Ali told the Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour in 1985 of his iconic character:

“He was the age I was when I had left Palestine and, in a sense, I am still that age today. … The character of Handala was a sort of icon that protected my soul from falling whenever I felt sluggish or I was ignoring my duty. That child was like a splash of fresh water on my forehead, bringing me to attention and keeping me from error and loss. He was the arrow of the compass, pointing steadily towards Palestine. Not just Palestine in geographical terms, but Palestine in its humanitarian sense — the symbol of a just cause, whether it is located in Egypt, Vietnam or South Africa.”

It comes as no surprise that Handala’s likeness has appeared in graffiti everywhere, from the Separation Wall in Palestine, to the backstreets off Tahrir Square in Cairo, to London.

In death, Ali has inspired a new generation of bold political cartoonists across the Middle East who are carrying his legacy forward. Khalid Albaih, the Qatar-based cartoonist, cites Ali as a crucial inspiration, as do myriad illustrators in the Levant and North Africa — and of course in Palestine.

“My mother used the cartoons of Naji al-Ali to tell us what was happening in Palestine while we were living in Kuwait,” said Mohammad Sabaaneh, 38, a Ramallah-based political cartoonist who continues to see Ali as a reference. “It’s important to continue what he started.”

“Not all of the cartoonists at this time could criticize the Arab regimes,” said Sabaaneh of the late Ali. “He criticized all the Palestinian parties, all the Arab regimes, and he talked about the poor people, the people who want to go back to Palestine.” Unlike most cartoonists of the time, Ali was not affiliated with a particular political party or party newspaper. That’s why Sabaaneh says, “He represents all Palestinians.”

Like his predecessor, Sabaaneh bravely skewers all authority. He has been arrested by both Israel and the Palestinian Authority, and also received death threats from Hamas.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

In Sabaaneh’s intense and angry lines, we can see great similarity to the black and white cross-hatching so iconic in Ali’s work. Both cartoonists present imagery that is simplistic yet detailed, that offers not a punch line but a provocation.

Sabaaneh told me that there is no archive or museum for Ali’s work in Palestine. “I don’t think they would do that because in most of his cartoons he criticized the [Palestinian Liberation Organization] PLO and Fatah,” he said. “That’s why you cannot find any Palestinian production about Naji al-Ali,” he added, discussing the renowned 1992 biopic, an Egyptian film starring Nour el-Sherif.

But in remembrance of Ali’s audacious critique of authority, fans and followers are hosting exhibitions in Amman, Jordan, Beirut, Lebanon and in the Ain al-Helweh refugee camp. Next month, the British Library will launch an exhibition of his original works.

Three decades after his death, the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza continues apace; Arab states often undermine one another rather than fight for Palestinian independence. And new conflicts, like civil wars in Syria and Yemen, are creating new generations of young refugees.

Looking carefully at Ali’s cartoons, one can grasp why they remain so popular and so relevant. Little has changed in the region. Consider the images that go viral, including the young boy Aylan Kurdi who died on the beach after fleeing from Syria. Or the 10-year Omran Daqneesh who survived an airstrike. Conflicts continue all around the world but it’s only the images of young children in the midst of them that seem to shake the apathetic out of their slumber.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)