African American Ira Aldridge, a Shakespearean actor in the early 1800s, honored in England

This painting by William Mulready portrays Ira Aldridge, as Othello, in battle armor.

If you think you know Jane Austen's England, think again. It was a little more diverse than you might imagine. London's first Indian restaurant opened in 1810. And then in the 1820s, a young American man burst onto the scene and quickly became one of the country's leading Shakespearean actors.

His name was Ira Aldridge. And he was black.

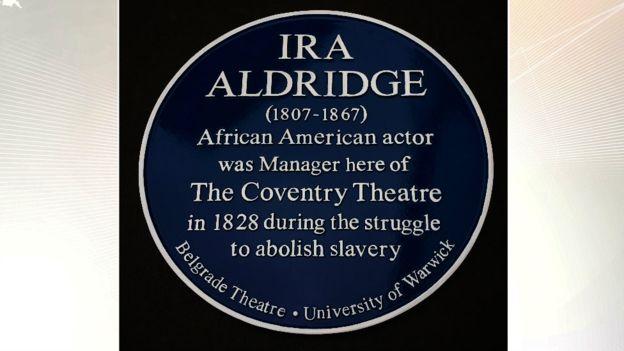

This week, Aldridge was honored in the city of Coventry with a plaque on the site of the theater where he first came to prominence.

The honor was spearheaded by Tony Howard, an English professor at the University of Warwick, in England. He also heads up the Multicultural Shakespeare project.

Aldridge was born free in New York City in 1807. Slavery was still widespread in the United States, although New York state was in the process of emancipating its slaves. His father was a lay preacher, and he wanted his son to go into the clergy.

He may have had some clerical training, but he was drawn to theater. But American black actors faced fierce hostility from their white competitors.

“You actually got a lot of opposition to black performers,” says Howard. “He was beaten up in the streets. So, he decided to go to the UK, to England, and try there. And he became one of the great Shakespearean actors of the 19th century.”

But it was a tough road. Aldridge encountered incredible racism. Nevertheless, he persisted.

“His audiences were divided,” says Howard. “There were those who said this is a very interesting and extraordinary young actor. And the fact that he's a black actor makes it more interesting and fascinating. But for many people, it was an insult because this is still a society where there is a great deal of slavery in the British Empire. And in order to combat the idea of increasing abolition, performers like Ira had to be stopped. And so there was a great deal of violent aggression. Not physical violence this time, but violence in the press.”

Howard says some of the things written about Howard were obscene. The common thread, says Howard, was the view “that essentially, this is not a human being. This is someone from Africa. Therefore from a slave culture. One review said ‘we have seen performing horses, we've seen performing dogs. Now this.’ So, astonishing stuff. But on the other hand, there were many people who just recognized a great talent.”

A lot of that racism was linked to the fact that Aldridge was interpreting Shakespeare, the icon of English literature.

“It was OK if he was playing one of the black roles in popular melodramas,” says Howard, “but doing Shakespeare [was] a kind of violation. He has no right to do that, not even to play Othello.”

In fact, Aldridge pioneered the role of Othello as a black actor. Previously, theaters had preferred actors who appeared to be Middle Eastern.

“Increasingly, what Ira was praised for was his realism,” says Howard. “And so I think increasingly he drew on his own experience and his own feeling.”

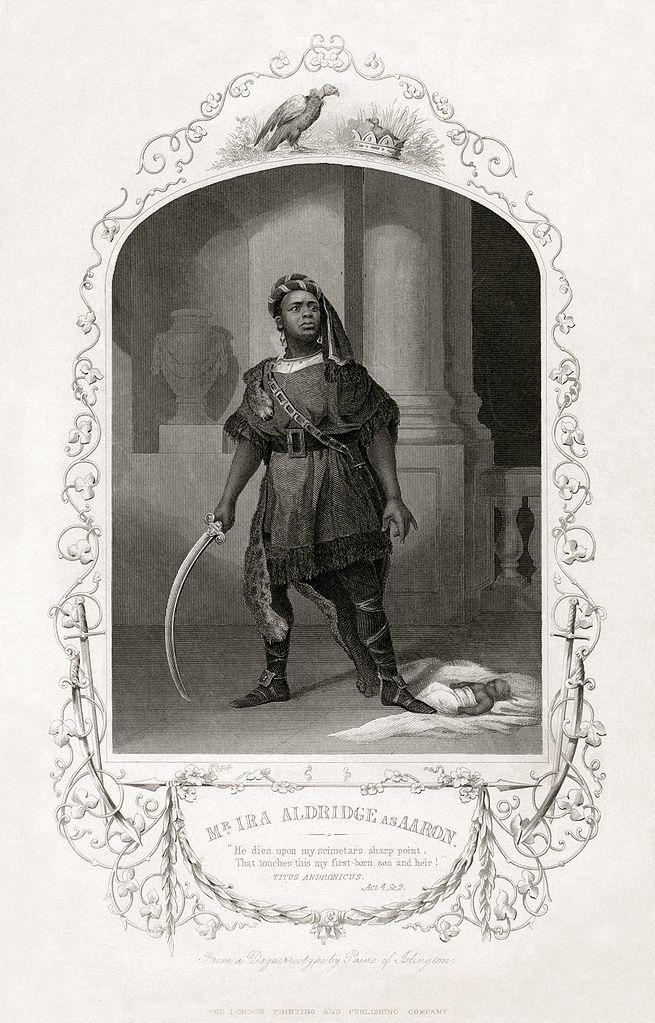

He was not confined to stereotypical black roles. He also played Aaron in "Titus Andronicus" and "King Lear."

Aldridge went on to tour throughout Europe and was especially popular in Germany and Russia, where he was honored by kings and princes.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Howard says he had no problem finding support for the idea of honoring Aldridge. “Everybody wanted to help. Times change. A city goes through dark periods and happy periods, but you have to have a sense of history and culture to carry you through.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?