You’re welcome to visit the longest beach in the world — unless you’re a refugee

Inani Beach, an 11-mile beach on the Bay of Bengal, makes up part of Cox's Bazar 75-mile sea beach — one of the longest beaches in the world. Bangladesh's tourism ministry wants to grow tourism to the beach, which it claims is the longest in the world, but many locals say development is hampered by hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees living in the area.

It was a hot Saturday in May when Bangladesh’s prime minister dipped her feet in the ocean. Sheikh Hasina was visiting the beach town of Cox’s Bazar and, like anyone else, she wanted to take a barefoot stroll. The beach runs unbroken along the Bay of Bengal for 75 miles, enough to make it the world’s longest, according to the government’s tourism board.

But it “has been always neglected,” Hasina said. “It's our duty to turn it into a lucrative tourist destination."

Nearly two million people are estimated to come to Cox’s Bazar each high season, which runs from November to March, but the vast majority of them are Bangladeshis from other parts of the country. Hasina came to the town, in Bangladesh’s southeast, to cut the ribbon on a slew of projects designed to bring in even more tourists, especially foreigners, including an expanded airport runway, new wide-body Boeing flights and a 50-mile seaside road.

Yet according to many locals, there’s still one major barrier that remains: the hundreds of thousands of refugees who live next door.

‘Local people do not like them’

The refugees, who are Muslims of the Rohingya ethnic group, have been called the most persecuted minority in the world. At home in overwhelmingly Buddhist Myanmar, they have been denied citizenship and have seen most of their rights steadily stripped away. As many as 500,000 have fled to Bangladesh and now live in villages scattered near Cox’s Bazar.

Bangladeshis are sympathetic, but many see the refugees as a threat to their livelihoods.

“The refugees may be some problem because they are involved in some subversive activities,” said Mohammad Sarwar Uddin, the manager of a pair of motels in Cox’s Bazar. “This is, of course, a problem for this area, for the development of tourism in this area especially.”

Many locals accuse the Rohingya of degrading their small corner of Bangladesh by cutting down forests, committing crimes and spreading disease. They traffic methamphetamine known as yaba and sell women and girls as prostitutes, locals allege.

“Local people do not like them,” said A.K.M. Fazlul Karim Chowdhury, the principal of Cox’s Bazar Government College. “They polluted the environment in every aspect: in socioeconomic, disease transmission, deforestation. In every sector.”

The sentiment is widespread. The “adverse effects” of the refugees were a prime point of discussion when the UN’s chief refugee officer visited the country in early July, according to the Foreign Ministry.

“Lots of the [refugees] are suffering. They have no land, they have no house. So what can they do? They need food.”

The government has not provided data about the refugees’ involvement in the drug trade or other crimes.

But illicit jobs can be attractive to the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya without access to official services, acknowledged Didarul Alam Rashed, the executive director of NONGOR, a group that works with the Rohingya as well as local drug addicts.

“Lots of the [refugees] are suffering,” he said. “They have no land, they have no house. So what can they do? They need food.”

Ironically, Bangladeshi locals are often the ones who coax refugees into illegal activities, he added. “We are using them!”

Salvation across the river

For the refugees, Bangladesh can feel like heaven — even with the hostility they sometimes face.

Hamida Begum, 40, fled to the country late last year, on the heels of a crackdown by the military in Myanmar. Soldiers attacked her village, Kyet Yoe Pyin, and killed her neighbors indiscriminately, in incidents documented by human rights groups. Satellite photos analyzed by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch showed that at least 240 structures were destroyed in her village. According to Begum, one family was locked inside their home before it was set ablaze.

Related: This Muslim purge in Myanmar is so awful you can see it from space

After the attack, Begum spent a week scurrying through the jungle to reach the Naf River, which divides Myanmar from Bangladesh. At every moment along the way, she was terrified that government soldiers would find her and gun her down.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Once she reached the river, it took only an hour to cross. Begum was packed into a small rowboat with roughly 20 other Rohingya, alongside nearly a dozen other boats like it. Other refugees were attacked by military speedboats, she recalled. Some of them fell out of their boats and were pulled back to safety. Others weren’t so lucky and disappeared into the river.

Only when she arrived on the western bank of the river did she finally feel safe. Bangladeshi border guards welcomed her and her companions with open arms.

Unofficial status

As a whole, however, Bangladesh has been reluctant to welcome the refugees too warmly, worrying that any embrace will be interpreted as an invitation for more Rohingya to cross the border. The country is already one of the most densely populated on the planet. Refugees undercut local workers and strain government services, Bangladeshis claim.

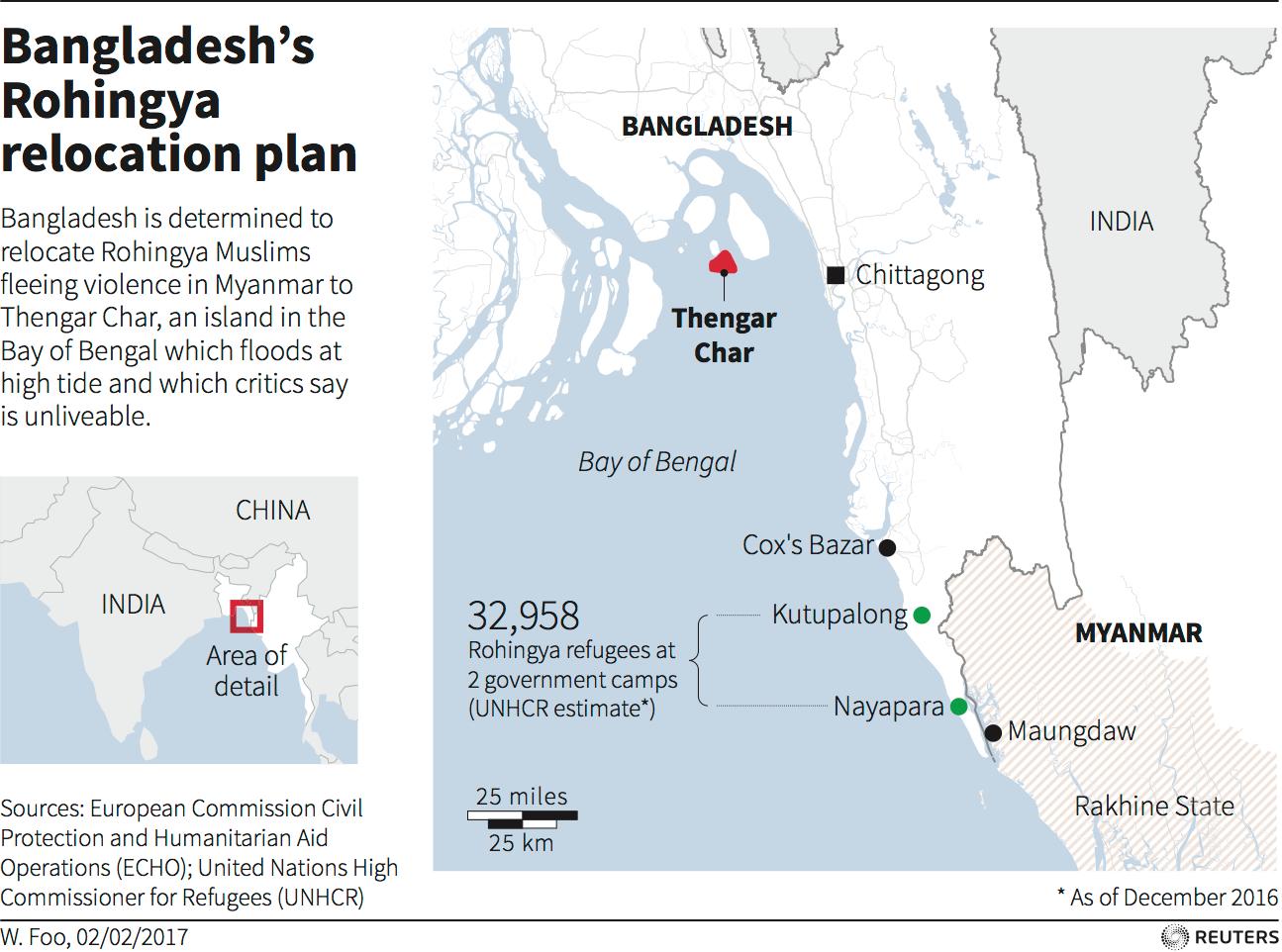

As a result, only 33,000 refugees live in the two official refugee camps maintained by the UN. Hundreds of thousands of others live nearby in unofficial camps and villages.

The difference between the two arrangements becomes clear during catastrophes, such as when Cyclone Mora ripped through the region in late May, flattening hundreds of huts. Those outside the official camps, who are more likely newer arrivals, were less prepared.

Begum suffered through the storm in her home outside one of the longstanding makeshift camps, called Leda. She pays occasional rent to a local man who found her and her neighbors living on the streets. But money can be difficult to come by.

Related: Myanmar's army is tormenting Muslims with a brutal rape campaign

Many refugees turn to the sea, setting out each day in wooden U-shaped fishing boats that can trap them in a life of debt.

Aman Ullah, 30, came to Bangladesh a decade ago and now lives along the tree line near the beach. He and four other fishermen work on a boat owned by a Bangladeshi man who gave them a startup loan of $125 several years ago. Now the boat owner gets half of each day’s profits, leaving each worker with a cut of just one-tenth of the total. Often, Ullah and his crewmates will take home just a dollar or two, not enough to afford the fish they catch.

“Just life with rice,” he said.

Ullah remains indebted to the boat owner and can’t leave until he repays the original loan. Occasionally, he said, the owner beats him and his crewmates if the catch is low or if they don’t follow his instructions.

Still, Ullah and his family of six children feel safe in Bangladesh. They are scraping by, he explained, but at least they are living.

Have to keep moving?

After escaping Myanmar, the Rohingya refugees may be forced to move once again.

In January, Bangladesh issued a directive calling for refugees to be relocated to an isolated island hours from the mainland, called Thengar Char. The island floods during bad storms and is believed to be frequented by gangs of pirates.

“The new arrivals are afraid of Thengar Char island,” said Mohammad Dudu Mir, 47, a Rohingya refugee who has been in Bangladesh since 2003. “Many people [don’t] like to go there because they are afraid of the cyclone and flooding.”

Bangladesh has toyed with the idea of relocating the refugees for years, and some watchers believe that Thengar Char is just an idle threat. Government spokespeople did not respond to an inquiry about efforts to relocate the refugees.

Shinji Kubo, the Bangladesh country representative for the UN’s refugee agency, is not quick to dismiss the plan.

“It has come from the highest level of government leadership, so there is a degree of seriousness and general intention to try and address it by relocating people out of this location,” he said.

Kubo’s office has declined to explicitly endorse or criticize the plan, since details remain murky. “But as long as it is done through a consultative and voluntary process, clearly benefiting the refugees [and] improving the well-being of refugees, it is probably up to the government’s decision,” he said. “But we are quite far before that.”

Locals in Bangladesh aren’t entirely sold on Thengar Char either.

“If you take huge numbers of Rohingyas at Thengar Char, other Rohingyas are coming from Myanmar. They are taking their place,” said Norun Hudar, the secretary of the small village of Whaikhyang, near the Myanmar border.

Instead, he said, Bangladesh should build a fence along its border with Myanmar, “just like Donald Trump” and the US president’s proposal for the US-Mexico border. Buddhist nationalists in Myanmar have proposed a similar solution, to stop what they allege are unauthorized immigrants from Bangladesh coming into their country.

For Begum, anything is preferable to the violence she escaped back home.

“If we have to go to Thengar Char, it is better than if we go to Myanmar,” she said.

As hotels continue to rise around Cox’s Bazar, locals grumble that the government is ignoring the refugee situation. If the pressure continues to grow, the promise of tourist dollars may compel it to tell the Rohingya to keep moving.

Julian Hattem reported from Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. His reporting was supported by the International Reporting Project.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?