This is the data we no longer get about immigration enforcement under the Trump administration

US Attorney General Jeff Sessions, on the right, joined White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer for the daily press briefing on Monday, March 27. He reiterated the Trump administration policy to punish cities and counties that do not detain immigrants on behalf of the federal government by withdrawing federal grants.

When US Attorney General Jeff Sessions warned sanctuary cities and counties in a press conference on Monday that they could lose federal grants, he cited a new immigration report about immigrants who were not detained by immigration officials:

“The charges and convictions against these aliens include drug trafficking, hit and run, rape, sex offenses against a child and even murder,” he said.

The examples he gave come from a report that attempts to make the case for why local law enforcement agencies should comply with detainers. A detainer is a federal request for a local law enforcement agency to hold an individual up to 48 hours after his or her release to give immigration agents additional time to decide whether to deport someone. Put simply, so-called sanctuary cities and counties do not always honor these requests.

More: America’s sanctuary communities span 30 states and 92 percent of the population

Donald Trump signed an executive order in the first week of his presidency that threatens to withhold federal funding for local jurisdictions where law enforcement agencies continue to refuse detainers. He also called for the creation of a weekly “comprehensive list of criminal actions committed by aliens and any jurisdiction that ignored or otherwise failed to honor any detainers with respect to such aliens.”

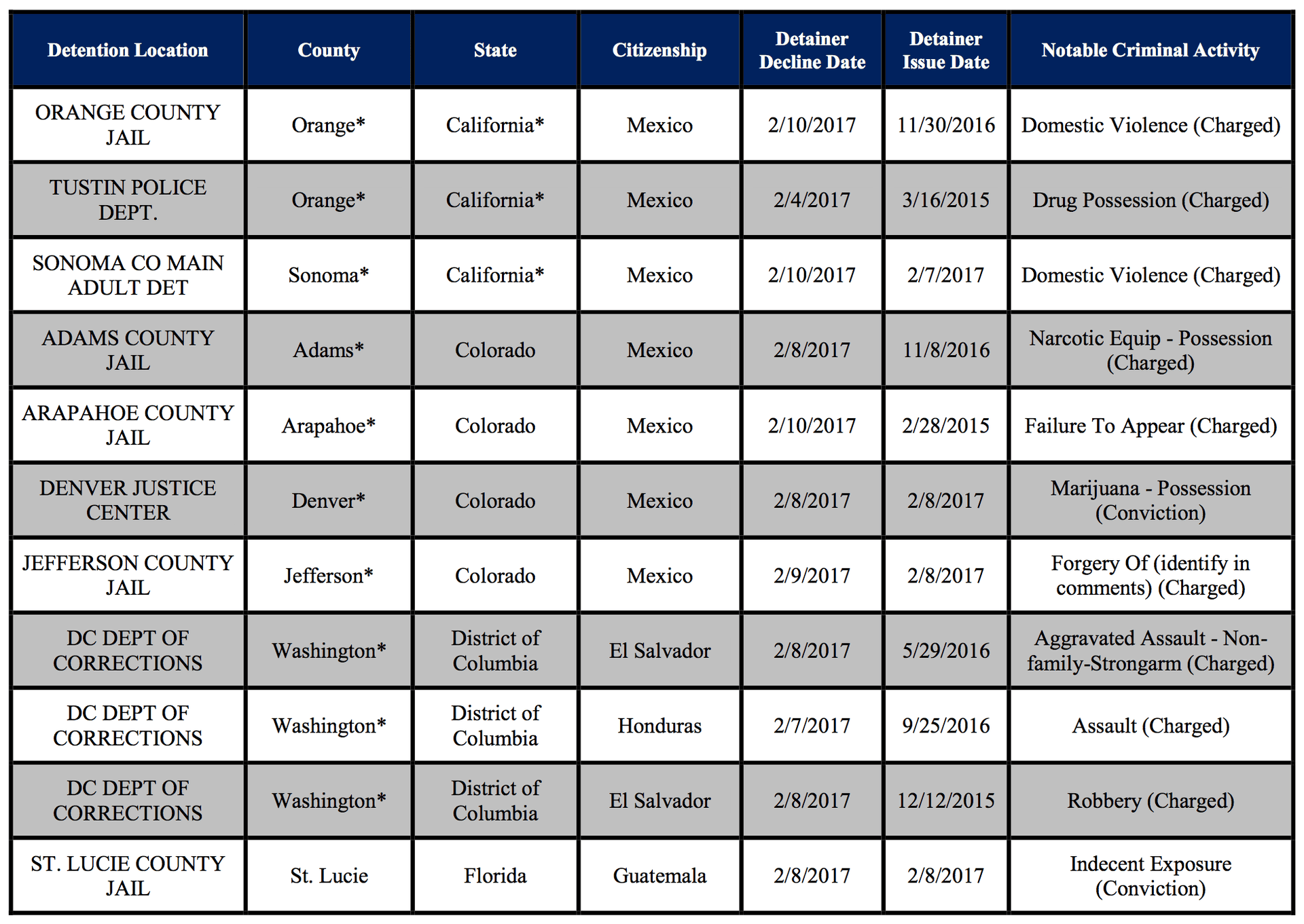

Thus, the creation of the “Declined Detainer Outcome Report” from the Department of Homeland Security. Now in its second week, it lists which municipalities didn’t cooperate and some details about the people they released during a single week from a Saturday to a Friday about two months prior. Data from the first report includes declined detainers from January 27 through February 3.

Early in the Trump administration, as part of 100 questions PRI is asking over his first 100 days in office, we asked if he would increase public information about his increased immigration enforcement.

But this report provides just a fraction of the data that used to be available about the detainer process.

Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) did not respond to several requests from PRI for comment, or information about what data they intend to provide in the future.

What data we did get pre-Trump was hard earned, often from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a nonpartisan data-gathering program at Syracuse University. TRAC has spent years filing Freedom of Information Act requests and fighting lawsuits to gain access to information about how detainers are used, and about how immigration enforcement works.

The datasets now available on the TRAC website include a database of all detainers issued from 2002 through 2015. It also includes records of how many people were deported from 2003 through 2016.

“We put up both the detainer app and the removal app to allow the public to really zone in on the impact of detainers,” says Sue Long, co-director of TRAC and a statistician at Syracuse University. “[The government] just drastically cut back the fields of information they’re releasing, so we can’t update them.”

TRAC’s search tools allow anyone to look at the number of people detained or removed through a number of lenses, such as gender or type of criminal conviction, over a long period of time.

The new declined detainer report does not include the same level of detail. It lists the location where the detainer was issued, the immigration status of the person in question, the date of issue, and selected criminal activity.

And most importantly instead of reporting the outcomes of all detainers issued, the new report only identifies those that were declined.

“The ability to really examine the picture more widely is being withheld,” says Long.

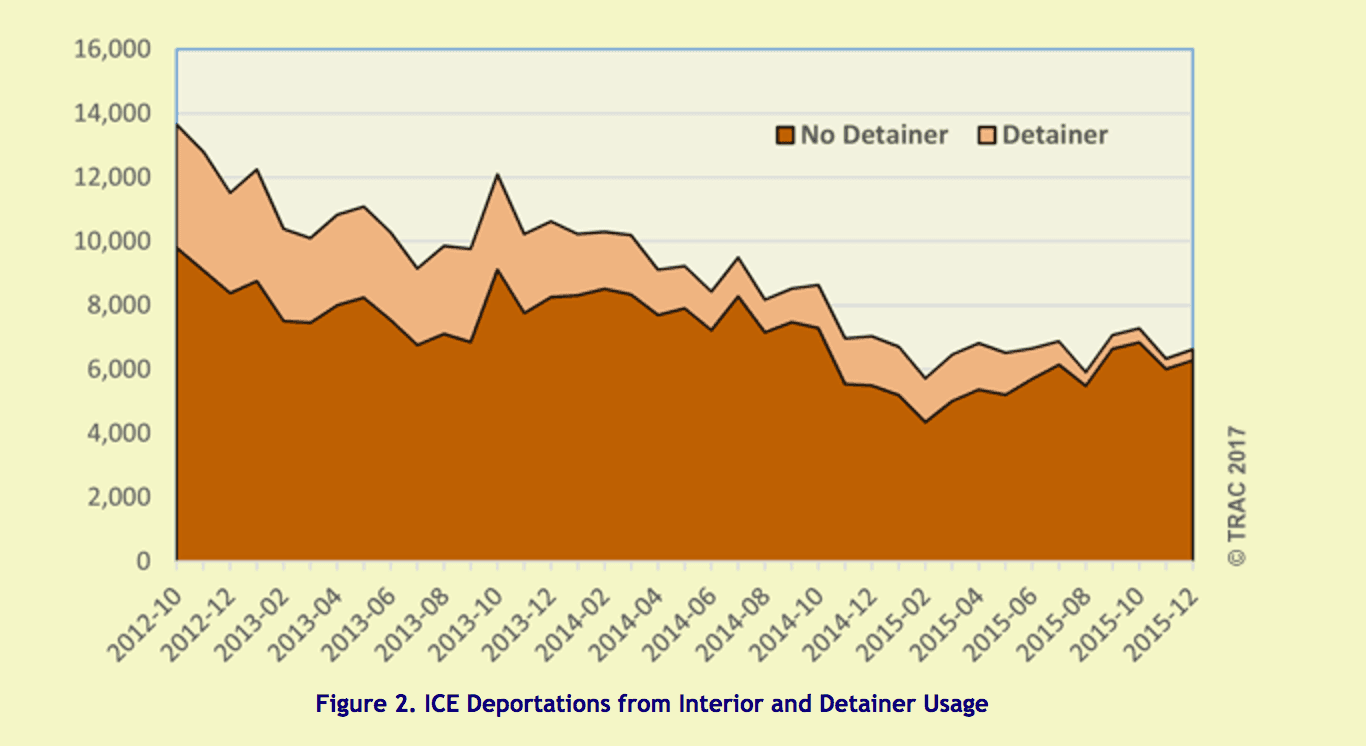

Earlier this year, TRAC released a report that analyzed the role of detainers during the Bush and Obama administrations. They found that detainer usage peaked in August 2011, when 27,755 were issued. The same report found that over a three month period in 2015, only 5 percent (1,100) of deportations from the US were associated with these detainers.

Long says she does not have enough information to continue these kinds of analyses. Other data now being withheld includes whether or not ICE actually took people into custody after issuing a detainer, as well as more complete criminal histories and details about where the deportation process begins.

For people who use TRAC data, the new government releases are not nearly enough information.

“It doesn’t replicate the unbiased picture that’s being made available by TRAC,” says César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, an immigration law professor at the University of Denver. “It allows us to see if there are discrepancies in how detainers are being used.”

He says the report “reads more like an extended press release” than an information release.

The data is also provided via a PDF, instead of as a spreadsheet or some other easily useable format.

“PDFs are nice but PDFs can’t replace the ability to sort, manipulate data by sorting it in different ways, like TRAC’s database allows us to do,” Hernández says. “It requires a lot more work to understand how enforcement efforts are shifting.”

The first declined detainer report from last week also suffered from some errors. It lists “non-cooperative jurisdictions,” which several counties challenged. In Nassau County, New York, law enforcement officials were angry to be included on the list after they said they would cooperate. Of the total 206 detainers declined, 128 came from of Travis County, Texas. The sheriff there had also recently changed his policy on detainers.

The report said 3,083 detainers were issued in total that week, but Long says it does not detail how many were issued to each law enforcement agency.

“Let’s say there were five refusals,” Long says. “It makes a lot of difference if it was out of five detainer requests or 500 requests. They’re not providing that information to the public.”

The reports include a category called “notable criminal activity,” which gives details about some individual detainers. In the first report, 75 people are listed as having been charged with a crime, 58 are listed as having been convicted, and 73 have no information about their criminal history. In the second report released Wednesday, 30 of the declined detainers are listed as people who have been charged with a crime and 17 were for people who have been convicted.

“People can get charged all kinds of things,” says Hernández “People get charged for things they don’t do, they get charged for things for don’t get prosecuted for, they get charged and prosecuted and sometimes there’s not enough evidence for a conviction.”

Dan Cadman is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, a conservative think tank in Washington, DC that advocates for reduced immigration. Cadman says he has a “love-hate” relationship with TRAC but has used their data in the past for his own analyses.

“One of the concerns that have is when I see ‘traffic offense,’” he says. “People always think ‘traffic offense’ means running a red light, but it can be driving under the influence, a hit and run. ICE has to give very specific instructions and enforce them to their agents about how they record them in their system. Garbage in and garbage out.”

Cadman was referring to a common saying among researchers that says if you don’t collect the right kind of data in the right way, you won’t produce good results.

Cadman says the sees value in the inclusion of criminal charges in the report. The Declined Detainer Report, he says, includes charges after the person has been arrested and been arraigned by a judge.

But, he says, more data would be better for everyone.

“Good data drives good policy and part of good policy is opening it up enough to the public so the public can participate and drive policy in the way they think is important,” Cadman says. “If I had my way, with the exception of anything that smacked of giving away national security information or law enforcement sensitive information, I would want scholars at minimum, the public possibly, to see virtually anything in their database that’s not prohibited by law.”