50 years ago, Americans finally got a look across the line of the Vietnam War

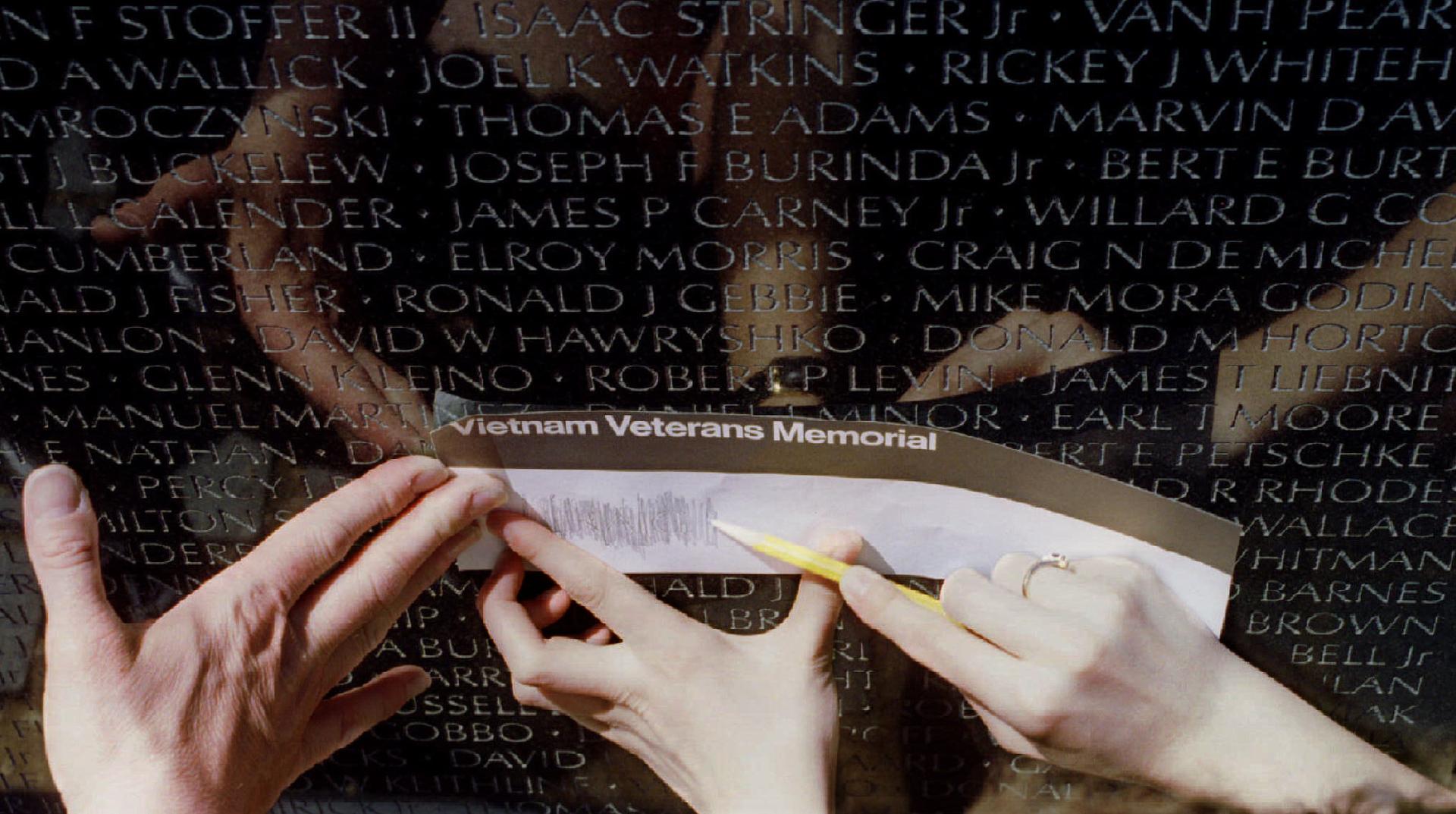

Relatives etch the name of Craig Swagler at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial April 29, 1995. Swagler was killed aboard a Navy boat that was sunk near Da Nang Feb. 27, 1969.

At the beginning of 1967, one place Americans couldn't go was Hanoi, North Vietnam.

It was two years after President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated the Vietnam War, and at home, the narrative of the first televised war was still that of good guys fighting for freedom.

But in late December 1966, that perspective changed.

Harrison Salisbury, a reporter for The New York Times who was known as a "journalistic one-man band," was granted access to North Vietnam, and became the first American to report from the other side of the war.

Salisbury's first article came out on Christmas Day 1966, a Sunday.

"Contrary to the impression given by United States communiques, on-the-spot inspection indicates that American bombing has been inflicting considerable civilian casualties in Hanoi and its environs for some time past,” Salisbury wrote.

Since the start of the war, Johnson and former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara said that US bombing in North Vietnam only targeted "concrete and steel, not human life."

On New Year's Eve, Johnson had a press conference at his ranch, calling Vietnam "the most careful, self-limited air war in history."

Salisbury's reporting continued into the first week of January.

"In the district as a whole, officials said, there have been more than 150 attacks since 1965. … The hospital has been dispersed into half a dozen thatched huts around the countryside. Authorities say it is too dangerous to occupy any substantial building. Most such buildings in the region, they say, have been hit by bombs."

As the gap grew between what people read and what the government said, Johnson doubled down in his January 10 State of the Union.

“Fear of external communist conquest in many Asian nations is already subsiding — and with this, the spirit of hope is rising,” he said.

Salisbury's reporting was getting through to Johnson, something that could be heard in a recorded conversation between the president and McNamara from January 1967:

Johnson: “Now what does The New York Times want?

McNamara: “The Times is internally split on the Salisbury articles, and they have some impression that we have some photographs that would support Salisbury, and they're just bound determined to get those photographs out of us.”

Johnson: “You tell 'em to go screw themselves as far as I'm concerned. Just say we don't owe The New York Times a goddam thing. We're not going to help you destroy this country knowingly.”

McNamara: “Yeah, this is what I've done.”

Some concluded that Salisbury was a turncoat working for the communist side, especially since he reported from Moscow for years. But in reality, the American government knew that Salisbury was onto something. A secret CIA memo in December 1966 found that over 75 percent of the casualties in the previous year were civilians. A month later, a CIA cable said that Salisbury's reporting was "good," but that he hadn't described the full extent of the damage.

“Mr. Johnson's position became attenuated because, really, just to take the flak over the main observation that I reported from Vietnam, which was that we were hitting civilian objectives and killing civilians,” Salisbury said in an interview in June 1969. “But an irrational position was taken for propaganda purposes, that we were bombing steel and concrete and so forth and so on. This was a position which I'm sure Mr. Johnson encouraged his propaganda people to take, because it fitted the image which enabled him to go farther with less opposition from the public. Well, this is fine up to a point, but once people see that this is not really so you're really out on a limb, and somebody gives it a little shake and you fall down. There's just no place to go but down.”

Meanwhile, J. William Fulbright, a US senator from Arkansas and longtime war opponent, began holding hearings on the war, and in his inability to get a straight answer from the Johnson administration. He said that there was “a credibility gap between what we know about the war, and what the administration was saying.”

Salisbury's reports eventually pressured McNamara to commission what would come to be known as the Pentagon Papers in June 1967, which would turn the credibility gap into a chasm.

Now 50 years later, that gap between what politicians say and what we know has grown so large that it now defines a post-truth world. You might think that now there's no turning back, but don't tell that to Harrison Salisbury, who might understand our current environment better than any of us.

“I've heard all the years that I've been a reporter, that what a reader wants is the truth, and nothing but the truth,” he said in 1968. “But it turns out that there are many truths. And the truth which is presented by a reporter in The New York Times or the Minneapolis Journal may not be the truth of the reader of that particular newspaper. If you don't believe that, try covering the man in the White House. And I don't care which man it is. My experiences, peripheral I will admit, have convinced me that there has never been anyone in the White House who liked a newspaper reporter."

Thanks to the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, which provided some of the archival material in this piece, and to independent producer Steve Atlas, is working on a radio documentary on LBJ and the Vietnam War that will be released this summer and will be distributed nationally by PRI.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.