In 1917, Jerusalem tried to surrender to a British army cook who was lost looking for eggs

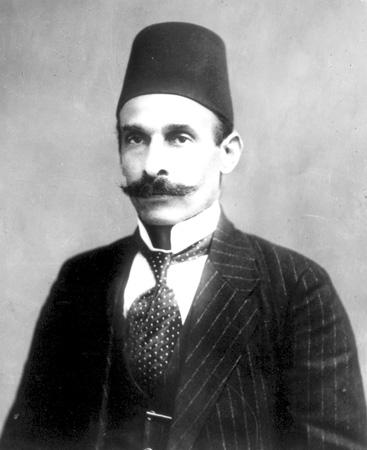

Mayor Husseini (center, wearing a fez), is pictured here with two British infantry sergeants the morning of the surrender of Jerusalem, on Dec. 9, 1917

December 9 is the anniversary of one of those epochal events that shaped the modern world. The fall of Jerusalem, in 1917, during World War I.

A Christian-led army — the British — took charge of the Holy City for the first time since the Crusades.

Their defeat of the Ottoman Turks opened up the entire Middle East to be reshaped by the victorious allies, for better or worse.

You would expect such a portentous event to be surrounded with grand and dignified solemnity, like a scene from the 1962 movie, “Lawrence of Arabia.” But the actual surrender of the city had a much more human, almost comical, quality.

A greasy little army cook got lost in the mist and changed history.

A witness, Major Vivian Gilbert, published his account of the fall of the Holy City in a book, “The Romance of the Last Crusade: With Allenby to Jerusalem,” which came out in 1928. He told the same story to the New York Times in 1921.

The Turks were allies of Germany in World War I, and so the Brits were attacking the Turkish empire from different directions. One army advanced from British-controlled Egypt into Turkish-held Palestine. Edmund Allenby was the commander of that British army.

Our witness Gilbert was a machine gun officer with the British 60th Division. After months of bloody fighting, he and his company bivouacked for the night not far from the ancient city — sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims.

The night was black, and Gilbert only realized he was just a few miles from the city when he heard its church bells striking midnight.

The next morning, Dec. 9, was misty, and the officers, hearing a rooster in a nearby village, summoned their cook and sent him off to get eggs.

Gilbert calls this cook, Private Murch, and describes him as “a miserable specimen,” a cockney from London.

“He hardly gave the impression of a smart British soldier,” writes Gilbert. “His tunic was so covered with grease and filth it looked black instead of khaki color … The toe-cap of one boot was missing, exposing to view a very red big toe, framed in a ragged grey woollen sock. He probably used his pith helmet as a pillow, for it had lost its original shape and had a twisted and drunken appearance; it was at least one size too small, and was only held in position by a thick piece of string doing duty for the leather strap it must have once possessed.”

Murch quickly gets lost in the mist and stumbles up and down rocky hills, looking for the village, and his eggs. He keeps stubbing his exposed toe on the rocks and stones lying everywhere.

Eventually, our hero, the liberator of Jerusalem, stumbles into a crowd of people waving white flags and trying to kiss him.

A carriage draws up, and a well-dressed man in a red fez greets him in English, and says “You are British soldier? I want to surrender the city please,” and tries to give Murch the keys.

“I don’t want yer city,” says the bewildered Londoner. “I want some eggs!”

The man in the fez was, in fact, the Mayor of Jerusalem, Hussein al-Husseini.

Gilbert says he was himself at battalion headquarters when Murch finally returned, “hot and out of breath.

“The perspiring private proceeded to relate his amazing adventures in a rich cockney dialect,” adds Gilbert.

Once he’d finished, the commanding officer turned and said, “Gentlemen, Jerusalem has fallen!”

But the farce had only just begun. The colonel informed his brigadier, who, hoping to be famous, went and received the keys from Mayor Husseini — and reported to his divisional commander that he had captured Jerusalem.

Not to be outdone, the divisional commander ordered the keys to be returned to the mayor, who had to wait for him to come and receive them.

Finally, the commander in chief himself, Edmund Allenby, ordered the keys to be returned to the mayor yet again, for him to receive formally on Dec. 11.

Poor Mayor Husseini died of pneumonia a few weeks later. Gilbert suspects he caught the fatal infection while outdoors in the cold of December, waiting to surrender to each of these different British officers.

*****

Meanwhile, a short while after Private Murch returned from his perambulations, our witness, Vivian Gilbert, was ordered to take his company through the city and set up a defensive position in the hills beyond. The Turks were expected to counterattack soon.

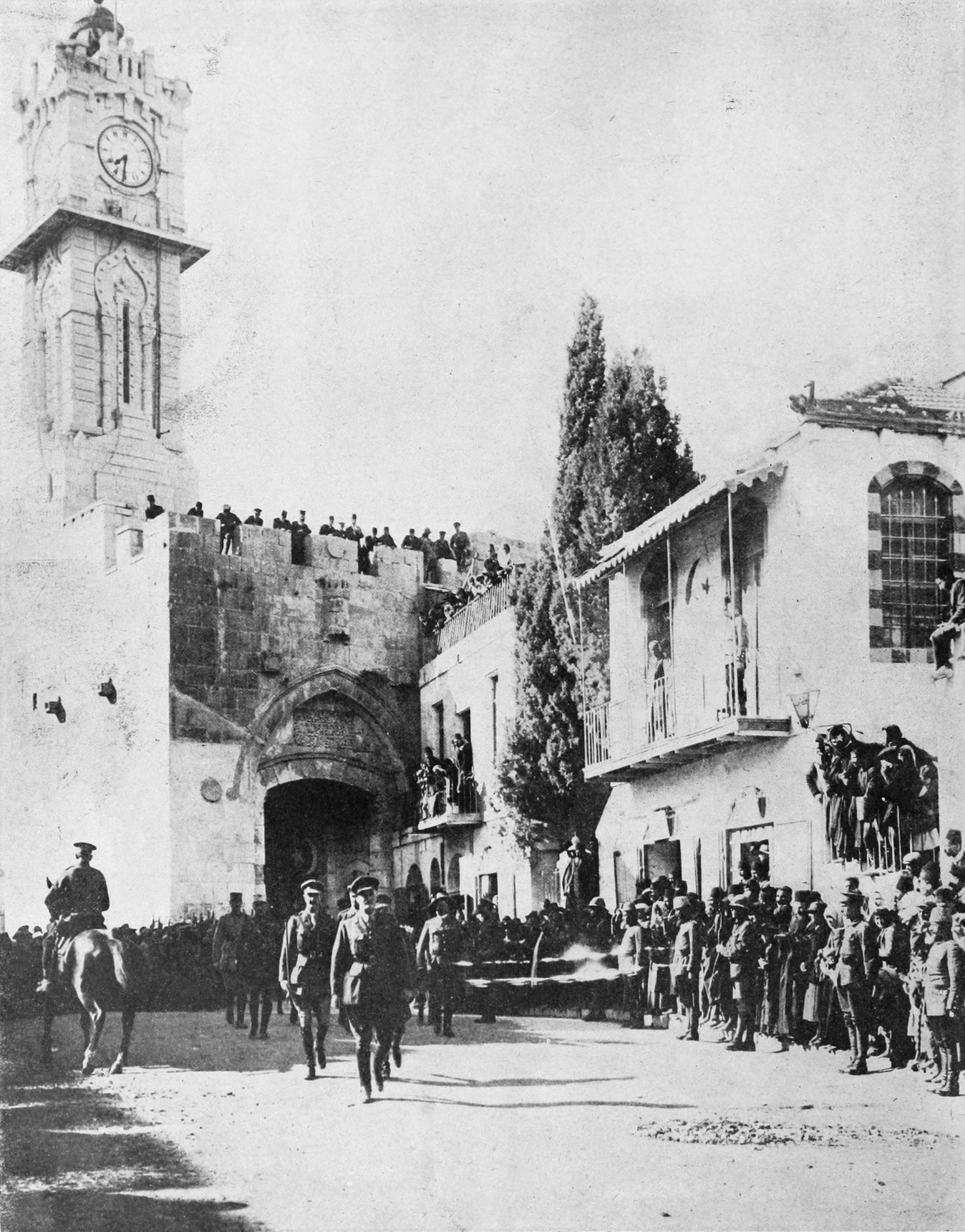

“Soon we reached the outskirts of the city,” he wrote, “and [we] began passing the more modern Jewish buildings that lie outside of the Jaffa Gate, and then at last we found ourselves inside the walls themselves — the first British troops to march through the Holy City!"

He continued: “The women had arms full of flowers which they showered amongst the troops; whilst the children, calling out English words of welcome, ran forward and seized the soldiers’ hands. Some of the older people kissed the guns and gun carriages, as covered with dust and mud they clattered over the cobblestones; for a battery of artillery, followed by two battalions of infantry, was close behind us. Venerable Jewish rabbis, with long grey beards, knelt in the mud by the wayside and with tears coursing down their furrowed cheeks, blessed us … "

The initial British occupation was cautious and sensitive, and there was a kind of honeymoon period, where everyone could believe that their dreams could come true: Jews, Christians, Arabs.

The commander-in-chief, General Allenby — a thickset man nicknamed, The Bull — saw himself as a moral man, fully aware of the responsibility that awaited him, taking control of Jerusalem.

He humbly entered and left the city on foot; he ordered that no British or any allied flags could be flown from anywhere in the city; he deployed Muslim troops, from India, to guard the Muslim holy places. He issued a proclamation, guaranteeing the security of the holy sites of the three great religions, and freedom of worship for all. Gilbert says he was “frantically cheered by the multitude.” Here's Allenby's own account of the fall of Jerusalem.

But as we now know, peace and happiness did not last long in Jerusalem and the rest of the Middle East.

To win the war, the British made contradictory promises that they could not fulfill.

A couple of weeks before the fall of Jerusalem, the British had issued the Balfour Declaration, promising the Jews a homeland in Palestine. Local British officers, including the famous Lawrence of Arabia, had promised the Arab peoples self-rule after the war.

But the only agreement that stuck was the deal that the British struck with their main ally in the war, France, to divide the Middle East between themselves. The Sykes-Picot agreement gave Palestine and Iraq to the British, and Syria and Lebanon to France.

The frustration of Zionist and Arab nationalism has shaped the history of the region ever since.