Mohammad Sayed in his workshop.

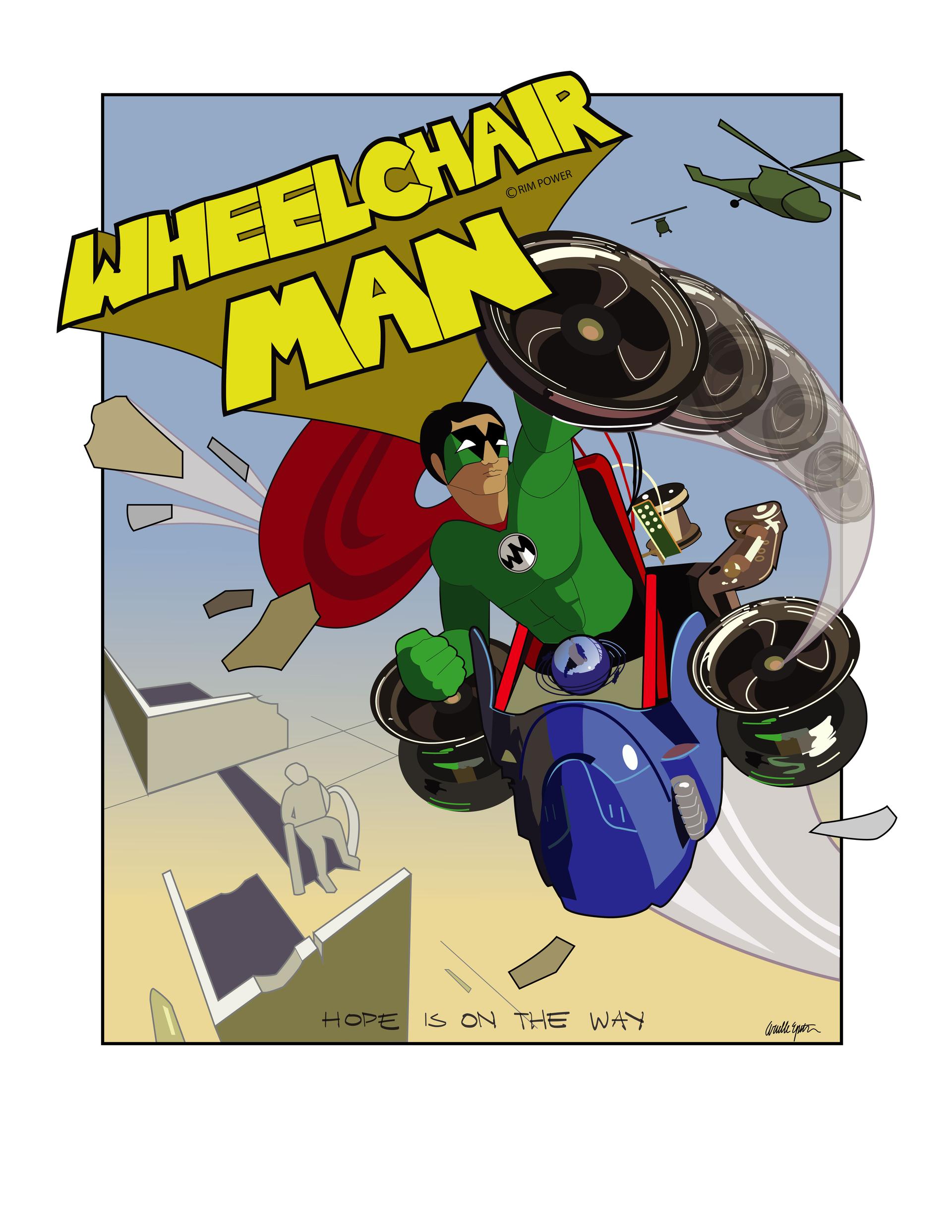

Mohammad Sayed is unstoppable. At the age of 19, he is already an inventor and entrepreneur. One half of his business, called RimPower, is providing assistive technologies. The other half is a comic book series centered around the hero Wheelchair Man.

“My goal is to help people in wheelchair[s] both psychologically and physically,” he says. “A world where every wheelchair user is empowered rather than disabled."

Sayed, who goes by "Mo," knows firsthand what that’s all about. At age 5, he suffered a traumatic spinal cord injury when his home in Afghanistan was bombed. It happened only days after he lost his mother to cancer. And as if things couldn’t get any worse, his father took him to a hospital in Kabul and never returned.

“Basically, I was on my own,” he says.

He spent seven years in a trauma hospital because he had nowhere else to go. To survive, he became a hustler, wheeling around the ward working odd jobs — repairing staffers' cellphones and taking pictures for photo IDs. He even taught himself English by listening to the BBC — and charged for translation.

“It was the uncertainty of ‘if this hospital closes, you have no place to go.’ So, you gotta act like you are no different than anybody who lives here. I think I just never gave up,” Sayed says.

He never gave up. Even when the hospital staff eventually had to evacuate, leaving him alone with just a few guards.

“The first month was really tough for me. I missed people because I would interact with patients, with nurses, with doctors,” Sayed says. “And all of a sudden, the place was like a ghost town. And I was the only living soul in it.”

His luck would change six months later, when Maria Pia-Sanchez, an American nurse working in Afghanistan, came looking for him. A doctor who knew Sayed asked her to check on him.

“So we stopped by the hospital where he had been living to see if anyone was there and if they knew where he was,” Pia-Sanchez says. “Just he and a couple of guards and a cleaner [were there].”

Even though Sayed was so young, Pia-Sanchez says he was entrusted with many things in the hospital that the older staff were not.

“He was given the keys to the pharmacy when they had to leave quickly because they trusted him to keep all that stuff safe. He was an amazing kid from everything that I had heard, so in a way it didn’t surprise me.”

Pia-Sanchez ended up adopting Sayed. And two years later, he moved to the US — with $600 of his earnings in his pocket, as he likes to point out. His new life in the suburbs of Boston came with a secure home and a mother who cooked and took care of him. But he didn't leave everything he'd learned behind.

“Even though that life has ended for me, you know, you will never feel certain,” the teenager says. “These are the kinds of things that stay with you. But what defines us as humans is that some of us don’t give in.”

His idea of not giving in started to shift when he learned about Mahatma Gandhi. That was his introduction to using non-violence as a weapon, and the whole concept blew his mind.

“Before learning about Gandhi, my role models were warlords,” Sayed says. “And I said I wish I had my legs so I could go kill these bastards — the Taliban.”

Those warlords were replaced with Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela. But in the pantheon of heroes, there was still a piece missing. And it wasn’t until Sayed attended Comic-Con in Boston a couple years ago that everything came into full focus.

“Most superheroes that come out is all about action and violence and at the end everything is destroyed and the hero becomes a hero because he destroyed everything,” Sayed says. “It’s like, what is the message you are sending to young kids?”

There’s a bit of a swagger to Sayed. His thick black eyebrows frame eyes that have a playful gleam. You can’t help but think that he is always one step ahead of you.

“So at Boston Comic-Con, I was like, why is there nobody representing the wheelchair community? Why isn’t there a wheelchair superhero wheeling around here?”

So he set out to make Wheelchair Man, an Afghan-American superhero who, upon making eye contact, shows a would-be criminal the consequences of his actions before he commits them. That’s his power. Throw in a wheelchair that can travel at warp speed with amphibious capabilities, and you’ve got yourself a pretty badass comic book hero. But what makes Wheelchair Man truly unique is that he’s based on a true story — Sayed’s story.

“In Afghanistan we don’t have superheroes, so this is a first. Especially, a first that is based on an Afghan-American. So I think a lot of kids in Afghanistan, when they read this, and they know about this story, it will really impact them,” he says.

Sayed has already completed a draft of the first edition of Wheelchair Man. He’s raising money with the crowd-sourcing website GoFundMe. His goal is to get copies of it into hospitals and rehab centers all over the world. He also has plans to build out a franchise that includes characters Captain Afghanistan, Wheelchair Boy and Wheelchair Girl.

“I tell you, I don’t want to scare Marvel, but if we have the right investors and right amount of money, we could compete. We have original ideas, original superheroes, it’s very different," he says. "Some people say different is bad but in this time and in this situation we are now, everyone needs hope and everyone wants peace and everyone around the world can relate to them.”

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DAmgzqgJUD10%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!