Teachers at Cali Calmecac Language Academy in Windsor, California, are focusing on community building after the election.

Third-graders at Cali Calmécac Language Academy in Windsor, California, are in the middle of presenting book reports when one boy bursts into tears. His teacher, Rosa Villalpando, pulls him aside to check in. Sobbing, he tells her that, as a result of the presidential election, he is afraid he will have to move to Mexico. Some kids on his street won’t play with him anymore, he says.

“They won’t let me because they’re like, ‘You’re a different color from us. Since Trump’s president, we can’t play with you,’” he says. “And my friend is moving to Canada, and other friends are going to Mexico. I want us to stay here and play with them. But I don’t have much time because I might move to Mexico.”

Villalpando leans in closer. “Know that I’m here, and you can talk to me, OK?” she says. The two take long, deep breaths together, and the boy slowly calms down.

Some children at this Spanish-English dual-immersion school, about an hour north of San Francisco, have been anxious since the primary election, crying in class or complaining of stomachaches, teachers say. Most students here are Latino, and even those whose families have been here for generations, and whose parents are US citizens, worry their families or friends could be separated under President-elect Donald Trump’s proposal to step up deportations.

“The night of the election, that was the hardest part, to know I would have to come in and face the children on their worst nightmare,” Villalpando says.

Teachers in many parts of the United States are grappling with this: How to create a safe space for students to express their fears, while also respecting all political views. Most people in Sonoma County voted for the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, but more than one-fifth supported Trump.

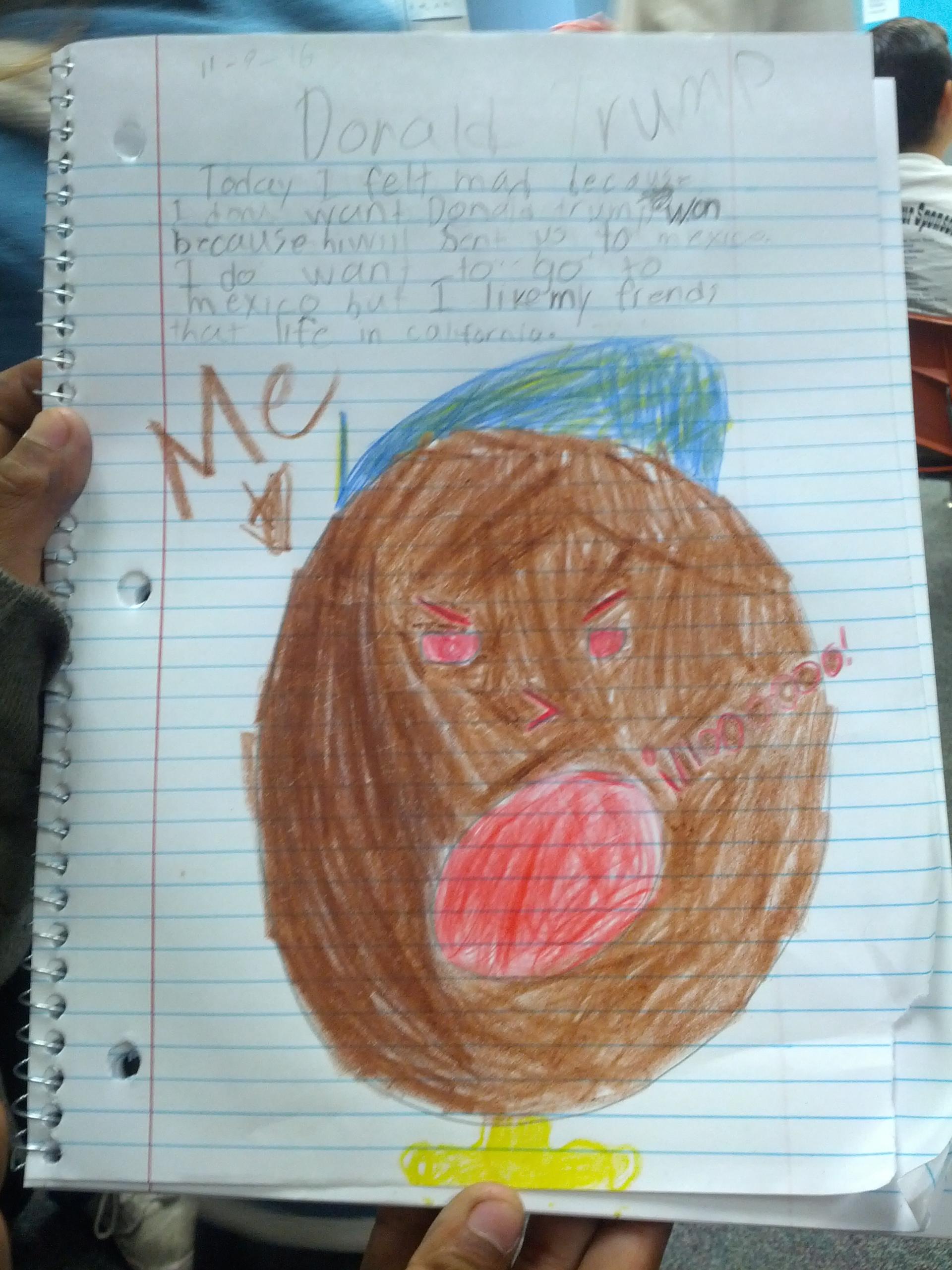

Villalpando asks her students to get out their journals and read what they wrote the day after the election. “It’s always a good thing to talk about how we’re feeling,” she reminds the class. “And, then, how do we turn those feelings into something positive?”

A few students write that their parents voted for Trump, or that Clinton was a “mean person.” But most share that they feel scared or mad about the new president-elect.

“Donald Trump may take my family away,” a girl named Saraí reads from her journal. “I don’t want my family away from me because I love them so much.”

For a lot of students here, the president-elect’s immigration rhetoric feels personal. Many identify as Mexican, even when they, and often their parents, are US citizens. So when Trump said he would build a bigger border wall and deport unauthorized immigrants, some children thought he referred to their families, even if their families could not be deported.

“I feel ashamed that America voted for Donald Trump,” says Cruz, 8 years old. “I feel like a lot of people are prejudiced because they voted for him.”

Overcome with emotion, Cruz begins to shake with deep sobbing breaths. A classmate sits down next to him to breathe with him.

“I can relate to the children’s fears, and I think maybe that’s why I’m sensitive to what they’re feeling,” Villalpando says. “I grew up in the United States, I came here when I was 4 1/2,” she says, pointing to a photograph in her classroom of her sitting with five brothers and sisters, next to their mom.

“I lived with fear because we were undocumented, and I did not become documented until I was 14,” Villalpando says. “But now this fear seems different to me, because not only is it governmental, but it could be anybody around you that may not agree with you. So it feels so much more personal.”

It feels more personal, in part, because shortly before the election, the school was tagged with graffiti that read, “Build the Wall Higher” and “Trump 2016.” Some kids were so upset they didn’t want to come to school the next day.

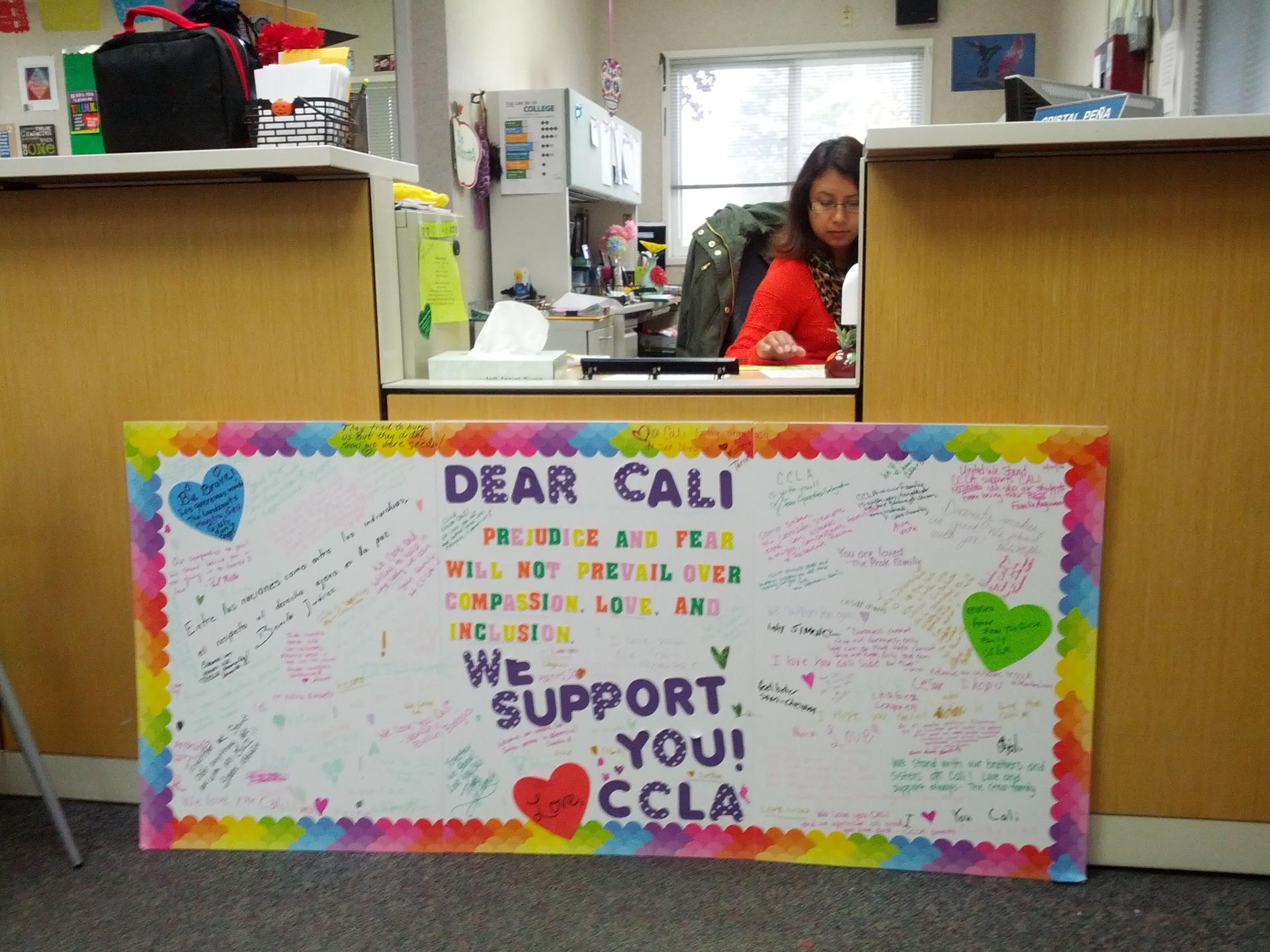

But two days later, community members welcomed the students with posters that said, “There are no walls in Windsor.”

Villalpando saw the incident as an opportunity to teach her students: “I took that upon myself to ask them, what kind of things do we do for others? And they came up with lists. 'Open the door for others,' 'Write thank-you cards,' 'Pick flowers for someone we love,' 'Just smile' … so we turned it around, and we did something positive with it.”

Those lessons are coming in handy post-election. Villalpando comes back to the list on the wall, again and again, to remind her students that even if we don’t agree, we are a community that supports each other, she says.

“It’s such a great time to be a teacher,” Villalpando says. “It is our place to show them love, and show them acceptance every day … that security. Some people may think it’s maybe doing too much, but I think it’s important. We can’t pretend it’s not happening.”

Some parents say Villalpando’s approach seems to be working. “The children’s stress has gone down a lot,” says Patricia Figueroa, a parent. “It’s not like when it first happened when they would come home really worried.” Even so, she says, her daughter still comes home and asks, “Mommy, are you going to have to go to Mexico?”