A Miami woman tells her story of what it’s like to be pregnant with Zika

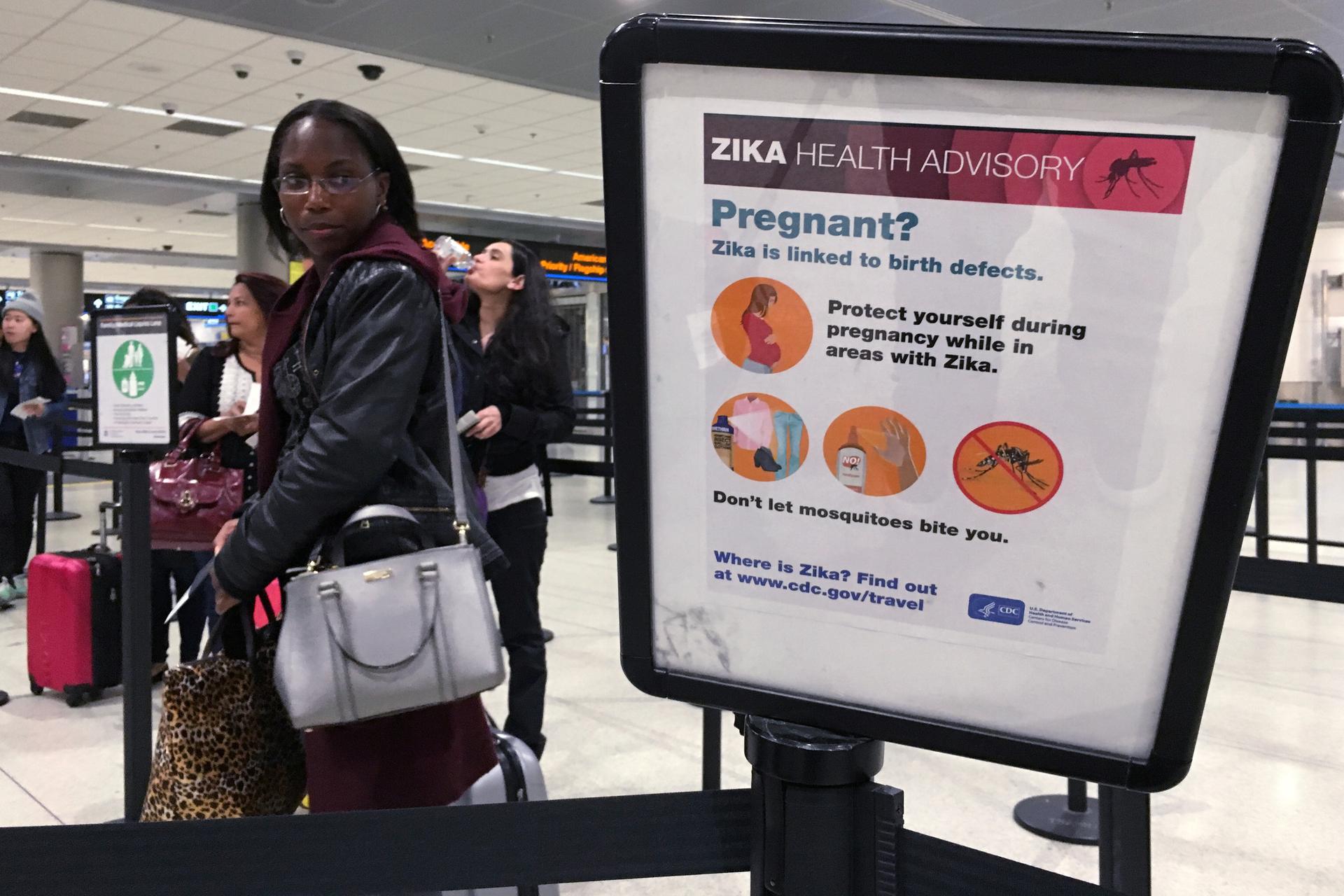

A woman looks at a Center for Disease Control (CDC) health advisory sign about the dangers of the Zika virus as she lines up for a security screening at Miami International Airport in Miami, Florida, U.S., May 23, 2016.

Sara lives in Miami Beach, Florida, and works in TV. She asks that we not use her real name because she and her husband haven’t told everyone in their family that during her pregnancy, she was infected with Zika.

They just found out at the beginning of October and she’s due in three weeks.

Like most people infected with the virus, Sarah never experienced any symptoms.

On August 19, Florida Governor Rick Scott confirmed that Zika was spreading in Miami Beach. Sara wasn’t in Florida at the time, but when she got back her OB/GYN recommended she get tested. Sara needed time to figure out how to pay for the test, as it wasn’t covered by her insurance, and once she got it, it took weeks for the results to come back. The news came on Oct. 7 — she was positive.

“He told me that I had tested positive for the Zika Virus, but that there was still a possibility — that there could be a false positive,” Sara says.

Her doctors tried to keep her upbeat. Since the Zika test detects the presence of certain antibodies, Sara’s doctor thought there might be a chance she had tested positive because she was exposed to another disease, such as dengue, yellow fever or chikungunya.

Sara works in the Latin American division of her company, which means she travels to the region a few times a year. But when the first news about Zika infections came out of Brazil, she and her husband decided she would not travel to the region at all. Her employer supported her decision.

After taking another test a few days later, Sara came back for a follow-up meeting. This time there was another doctor in the clinic.

“He had a much more somber spin on it and he said, ‘I think it's highly unlikely you have a false positive. You need to start thinking like you have this and you need to start preparing yourself for the possibility that your child was also infected.’”

Only then, Sara says, when she could no longer find comfort in the possibility that the result might be false, did the reality of her situation finally hit home.

The doctor told her that they’ll have to monitor the baby closely after it was born.

“Unfortunately, the information he had was very broad, and very high-level,” she says. “I'm one of these people that like to know the details and understand really what's happening next.”

All of the ultrasound scans Sara had done so far have shown perfectly normal results, but she’s mostly concerned because some of the problems associated with Zika, including microcephaly, can develop after birth.

One of the hardest things she faced was discussing the news with relatives. “It was very difficult,” she says. It took her and her husband a few days to process the news before they were able to say, “This is really happening, this is not like some bad dream.”

Because Sara and her husband are devout Christians, their primary reaction was to ask people to pray for them. “We realized that there's really absolutely nothing the doctors can do at this time,” she explains, “There's nothing I can do. It's just really outside of our hands. We started telling first some of our close friends that we felt could not just pray for us but pray for the baby, pray for healing, for protection, and just to give us strength.”

Before she got the news that she had been infected, Sara tried to take precautions to keep from getting Zika. When Zika-carrying mosquitoes arrived in Wynwood, which is just across the bridge in Miami, Sara started wearing long pants and jackets, even though it was summer. She also used mosquito repellent and the family spent less time outdoors. With the new regime, the long walks she used to take with her 3-year-old son along the beach became a thing of the past.

But now, after researching Zika on her own for the past three weeks, she realizes there’s more she could have done to avoid mosquitoes, particularly the main carrier of Zika, Aedes Aegypti, which is widespread in Florida. And that makes her frustrated.

“There was all kinds of information that I didn't know, that I didn't follow, that I think could have maybe helped prevent, because I think the best way to prevent being infected is preventing being bitten by this particular type of mosquito," she says.

Sara also has a message to women who are planning to get pregnant. She says they should “do the research” themselves, and visit the Zika Foundation website, as well as keep tabs on the latest updates on the virus from the CDC.

“What I definitely feel is that if we rely on others to inform us, even our own doctors, they're not necessarily [going to] have the most up-to-date, accurate information. I think some people are not taking this as seriously as they should,” she says.

America Abroad is an award-winning documentary radio program that takes an in-depth look at one critical issue in international affairs and US foreign policy every month. You can follow us on Facebook, talk to us on Twitter, and subscribe to our weekly newsletter for updates.